Missouri’s largest peach grower is suing Monsanto over claims that dicamba drift caused widespread damage to the farm’s peach trees. This is Monsanto’s first lawsuit over the illegal spraying of the herbicide on its genetically modified (GMO) cotton and soy that’s suspected of causing extensive damage to non-target crops across America’s farm belt.

The lawsuit, Bader Farms, Inc., et al v. Monsanto Company, Case No. 16DU-CC00111, was filed in Dunklin County, Missouri on Nov. 23. Bill Bader of Bader Farms in Campbell, Missouri claims that more than 7,000 peach trees were damaged by the drift-prone and extremely volatile herbicide in 2015, amounting to $1.5 million in losses. This year, the farm said it lost more than 30,000 trees, with financial losses estimated in the millions.

The complaint accuses Monsanto of knowingly selling dicamba-tolerant cotton and soybean seeds to farmers before securing federal approval for the herbicide designed to go along with it. Bollgard II XtendFlex cotton was introduced in 2015 and Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybeans was introduced earlier this year. However, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency only approved the corresponding herbicide, XtendiMax with VaporGrip Technology, last month.

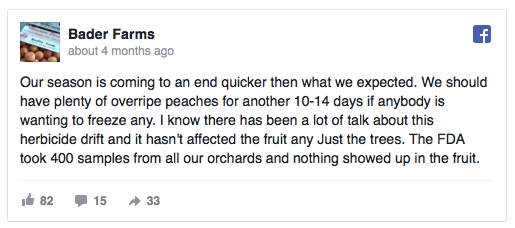

Even though the biotech company warned growers against illegal dicamba use on the crops, many farmers allegedly sprayed older versions of dicamba on the crops anyway to stop weeds. However, while Monsanto’s crops are genetically engineered to tolerate sprays of dicamba, other crops cannot. And since dicamba is extremely prone to drift, it can be picked up by the wind and land on neighboring fields, crops and native plants. In the fall, 10 states reported horrific damage on thousands of acres of peaches, tomatoes, cantaloupes, watermelons, rice, cotton, peas, peanuts, alfalfa and soybeans.

The EPA approved Monstano’s dicamba-based herbicides in November, but some farms were spraying illegal older versions prior to that. To read that story, click here. (Image: Twitter / EcoWatch)

Bader said in August that 400-500 farmers in his region have been affected: “If they don’t get compensation 60 percent will be out of business in two years.”

“We need to go after Monsanto. These farmers are being hung out to dry,” Bader added.

Bader’s lawsuit alleges that Monsanto chose to sell its Xtend cotton and soybean seeds knowing that such destructive spraying would be inevitable.

“Monsanto chose to sell these seeds before they could be safely cultivated,” Bev Randles of Randles & Splittgerber, the Kansas City, Missouri law firm representing Bader Farms, said in a statement. “We believe it is against Monsanto’s own practice, not to mention industry standards, to release a seed without a corresponding herbicide to protect the crop from destruction. But Monsanto chose greed over public safety and made farms in Southeast Missouri and Northeast Arkansas unwilling test labs for their defective seed system.”

The law firm expects similar lawsuits to follow. “Our firm continues to be contacted to help farmers who have been harmed by Monsanto’s actions,” Randles said. “They are folks who have supported Monsanto by purchasing their products for years, only to have been betrayed in the end. We expect more farmers to file suit in the coming weeks.”

In response, Monsanto said that the responsibility lies with the growers who illegally applied dicamba.

“Both prior to and throughout the 2016 season, Monsanto took many steps to remind growers, dealers and applicators that dicamba was not approved for in-crop use at the time, and we do not condone the illegal use of any pesticide,” the company said in a statement to Brownfield. “While we sympathize with those who have been impacted by farmers who chose to apply dicamba illegally, this lawsuit attempts to shift responsibility away from individuals who knowingly and intentionally broke state and federal law and harmed their neighbors in the process. Responsibility for these actions belongs to those individuals alone. We will defend ourselves accordingly.”

Monsanto developed its Xtend system to address “superweeds” that have grown resistant to glyphosate, the main ingredient in the company’s former bread-and-butter, Roundup. The firm expects to see 15 million Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybean acres and more than 3 million acres of Bollgard II XtendFlex cotton in 2017. According to AgWeb, the technology is also licensed to more than 100 additional brands. The company has invested more than $1 billion in a dicamba production facility in Luling, La., to meet the demand it predicts.

Critics, however, are worried about the herbicide’s potential threat to biodiversity, that it forces growers to switch to the Xtend system and that it only creates another round of superweeds. Dicamba-resistant weeds have already been found in Kansas and Nebraska.

“We can’t spray our way out of this problem. We need to get off the pesticide treadmill,” Dr. Nathan Donley with the Center for Biological Diversity said. “Pesticide resistant superweeds are a serious threat to our farmers, and piling on more pesticides will just result in superweeds resistant to more pesticides. We can’t fight evolution — it’s a losing strategy.”

(“Missouri’s Largest Peach Farmer Sues Monsanto for Losses From Illegal Herbicide Use” was originally published on EcoWatch and is reposted on Rural America In These Times in accordance with their Terms of Use.)