They Voted ‘No’ to Austerity. They Got ‘Yes’ Anyway. What Do Greeks Think About Tsipras Now?

We asked Athenians on the street how they feel about the Syriza leader’s acceptance of the EU’s terms and the lean times ahead.

Tomás Lynch

In January, the Greeks elected Alexis Tsipras and his radical Syriza party on a wave of defiance and hope. Since then, as the anti-austerity party fought for debt relief from the European Union, the hardline negotiations between Syriza and the financial institutions of the EU made weekly international headlines. On July 5, an overwhelming majority of the Greek electorate voted “no” to the conditions demanded by the European institutions in exchange for a third bailout. Yet, two weeks later, Tsipras pushed the same conditions through the Greek Parliament over the opposition of many members of his own party.

Nothing has provoked more global opining in recent weeks than the referendum and Tsipras’s apparent aboutface. But most of the speculation has been happening far from the shores of Greece. I traveled to Athens in late July to find out how the Greeks felt at a moment when their leaders, after bringing the country to the brink of an unprecedented, unpredictable economic revolution and a possible Grexit from the EU, pulled back from the edge. Walking around the streets of Athens, I talked to office workers and shop owners, anarchists and dog-walkers, students and rank-and-file Syriza members, about their hopes and fears for the future.

Mary and Yannis

“There’s something you haven’t told him yet,” says Mary. “We are both members of Syriza.”

Mary and Yannis have been talking about the despair of recent years. People still own their houses, but they have no services. The electric company and the water company cut many people off when they did not pay their bills. Last winter, people cut down trees along the streets and burned them to keep warm. “Austerity kills this country, step by step,” says Yannis. “Kills this country, day by day. Kills it, dream by dream.

“We said no, and now Tsipras says that we were really trying to say yes. He didn’t believe us. He didn’t believe in Greece, that we could do it ourselves. He didn’t believe in his party.” Yannis hesitates for a second. “Our party.”

He tells us to go to the protest that night against the second round of voting on austerity reforms in the Greek Parliament. Those protests appear to have been the last breath of the hope that fed and was fed by Syriza.

“And now what?” asks Yannis. “There is nothing now. We are in a long tunnel, and we can see no light at the end. Not even the light of the train coming. Just darkness.”

Dimitri

Dimitri is drinking coffee outside an expensive cafe on his break. He works in the shipping industry, he tells me. He offers me a cigarette.

He believes Tsipras will have to raise taxes on the big shipping companies as a result of the deal with EU. “And what do you think will happen then? They will move to another country that will give them better tax rates. Now all it takes is a phone call to an accountant in some foreign office to set the company up in Switzerland, in Singapore, in Hong Kong. A week later, and the company will be gone. All the jobs will be gone. … Tourism and shipping are all that Greece has.”

He owns a small cottage on an island, inherited from his father, who grew up there. “I went to it before Christmas, and again last week,” he says. “And in that time the supermarket had closed, and there is a new German supermarket now. All the food was imported, from Germany, from Holland. The Greek farmers who used to supply the old supermarket have nothing now.

“Why don’t we buy potatoes and meat from Greece? We can grow them here. But the Dutch meat is cheaper. With this new austerity the people will be poorer, and they will have to buy cheaper food, so they will go to the German discount supermarkets.”

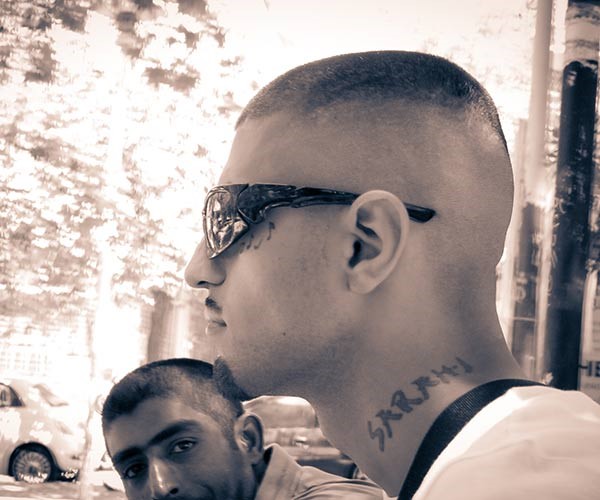

(Another) Yannis

_Yannis.jpg)

Yannis is smoking on a bench in Exarcheia square, the center of Athens’s radical and anarchist district, and the site of the student protests in the 1970s that shook the military dictatorship. He tells an arcane story of corruption dragged to light a few years before on the island of Agathonisi, where he was working as a waiter. A bomb was left under the mayor’s office; the man arrested was found to have placed it there on the mayor’s orders. It emerged that a net of corruption ran through the town: five-hundred Kalashnikovs were found in the churchyard; bodies were discovered in the sea with weights attached to their feet. “Like the Mafia,” I say. “Like the Mafia,” he affirms.

Greece is a midway point between Europe and the Middle East, Africa and the East. Which is why refugees flood into the country — from Libya, Syria, Pakistan — and why drugs and guns flow, why the politicians and the police can get rich.

“The problem is a human one,” he tells us. “Nepotism and corruption.” There is no easy solution.

What about the threat of Golden Dawn?

They have reached the limit of the popularity they can achieve, Yannis believes. They had nearly 20 percent of support in polls a few years back. But now people have realized that they are just Nazis. So their support has dropped. “But they say that a huge number of the army support them.”

A friend of his in the police force recalls that during his training, one officer once claimed not to believe in human rights. The great majority of the training officers cheered. Those who didn’t, shrank into their seats.

Kostis

Kostis is sitting with his girlfriend, Edara (who didn’t wish to be photographed) on a curb outside the National Technical University. Edara graduated with a master’s degree today. She shows us the roll of paper, tied with a ribbon.

“All the people thought that when they voted no they were saying to Syriza, to Tsipras, that we’re not afraid to go the whole way,” Kostis says. “That we’re not afraid to leave the Euro. We were ready to do it. But he didn’t.”

Will you leave the country now that you are finished studying?

“As long as I can live my life the way I want to, I’m not going to leave,” says Kostis.

They have to go, meet their friends, drink raki (the strong Cretan liquor) and eat meze. Next week, they are going away on holidays, to the islands. They are still arguing with their extended gang of friends about where: to the Western islands, or the Eastern? They go off together, she on a motorcycle, he on a moped, helmetless, yelling into their cellphones and at each other, dodging through the nighttime Athens traffic.

Ari

Ari is Turkish. He lived for two years in the U.K. and his English is clear and crisp, but his voice is taut with anger.

“I hate this country,” he says. “Nobody cares about anyone here. Go to Monastiraki, where the tourists are, lie down on the streets there and you will see. Nobody will come to help you. They will step over you.”

He waves a plastic bottle of water. “Look at this. In the U.K. nobody pays for water. But here you have to pay. Water should be free.

“If you kill someone, you will spend maybe a year in prison. I spent 15 months in a detainment camp when I came here. All of us sleeping together in the same big room, nothing to protect us from the cold in the winter. Another man had spent two years there. And for what crime? For not having the right papers. That was our crime. Two years locked away without a trial.”

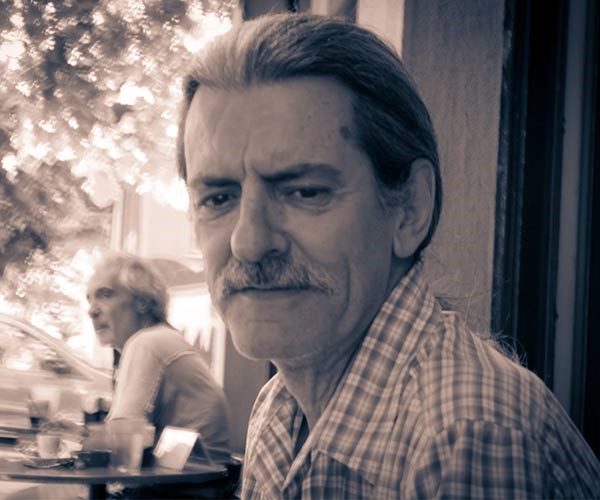

Mikis

Mikis is the owner of a coffee shop. He sits at a table on the street outside. Yes, things will get better, he believes. Not today, or tomorrow. But in some years, things will be a little better. And they will not get much worse.

Greece has more public servants than any other European country, he tells me — too many. Yes, there are the islands, and every island needs a doctor, a policeman. But still, there are too many. The politicians give jobs to their friends, their families, the friends of their families.

“Look,” he says. “The Germans are not so bad. All they are trying to do is make us like them. They are trying to make us into a normal, modern European country. They are trying to stop the corruption. They are trying to make everyone pay their taxes. We have to do this. We have to move forwards.

Vicky

Vicky sits on a window ledge in a graffitied alleyway in Exarcheia, smoking and drinking Coca-Cola. She is 37, she tells me. She wants to have a family, but she can’t. There is nothing here now, no job to support children with, no life to raise them to.

For years there were just two parties here, she says: Blue and Green. Conservative and Social-Democrat. You were cheated by the Blue for five years, then you voted for the Green, and they were just as corrupt. “They just wanted to eat our money.” The way she says “eat” makes me think she is looking for a stronger word, a word of her own tongue without a cognate in English.

And Tsipras?

“I like him,” she says. “I like him because of his personal life, unmarried with two children, in a country of carbon-copied families, polite husbands and wives with two identical children.

“Last night I was talking to my mother and I told her, if the war, the revolution comes — and it might — I will go out on the streets and fight. Not because I know what to fight for, but because I have nothing else to live for. No job, no family. Just you, mama.”