Arsonists Torched Highlander’s Main Office. But You Can’t Burn Down an Idea.

Labor, civil rights and social justice activists have trained at the historic Highlander Research and Education Center for generations.

Gary Stevenson

The main office building of the historic Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tenn., burned to the ground March 29. Later that day, white supremacist graffiti was found in the parking lot.

Thankfully, no one was harmed in the fire. But as one of countless organizers and activists who have passed through this center for popular education, I felt its loss deeply. Founded in 1932, Highlander (originally called the Highlander Folk School) connected democratic education with labor, community organizing and civic engagement. It was a meeting place and training grounds for generations of labor, civil rights and social justice activists. Rosa Parks and John Lewis made appearances, and Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Highlander’s 25th anniversary.

So when I saw a video on social media of the building being razed, I was taken back to the summer of 1998, when a group of about 45 Teamster organizers, warehouse workers and truck drivers from around the country gathered at Highlander to learn how to take on a formidable opponent: Overnite Transportation Company (part of the Union Pacific Corporation), based in Richmond, Va., the largest non-union trucking firm in the United States at the time. Overnite had resisted Teamsters’ organizing efforts since 1994. Recognizing we needed a continual pressure campaign for the company to take bargaining seriously, we sought inspiration for more aggressive tactics from civil disobedience activists at Highlander.

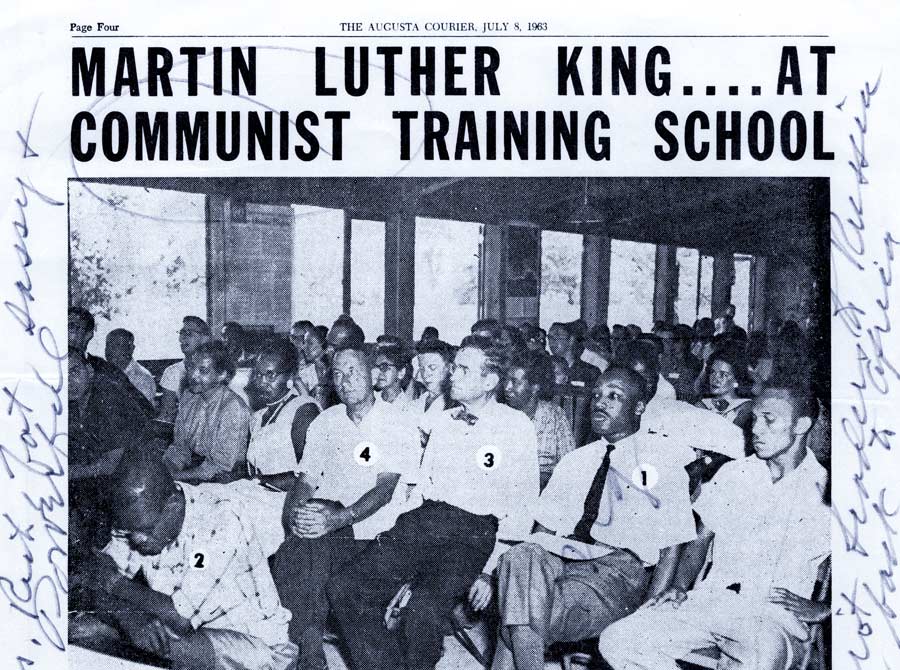

(A broadside calls Highlander 25th anniversary attendees Martin Luther King Jr., Abner W. Berry, Aubrey Williams and Myles Horton the “‘Four Horsemen’ of racial agitation.” Rosa Parks appears on the far left)

This was the same building I remember from 1998. It was octagonal, and workshops were held in a large room with rocking chairs arranged in a circle, a symbol of respect, dignity and welcome. Everyone had an equal chance to participate in discussion, tell stories and connect.

Our discussions at Highlander not only provided practical strategies for organizing and union building, but a way to connect to a larger movement for social and economic justice and the long history of organizing in the South.

One day, we received a visit from Candie and Guy Carawan, the folk singers who introduced “We Shall Overcome” into the civil rights movement. The two had been very involved with Highlander during the 1960s, sharing union songs and encouraging musicians to get involved in organizing.

“We Shall Overcome” was a gospel song said to have originated as a work song among enslaved people in the fields. Its first documented political use was among striking tobacco workers in Charleston, S.C., in 1945. In 1947, two of those workers attended a workshop at Highlander, where they taught the song to Zilphia Horton, Highlander’s music director. Zilphia began using the song in workshops, which had been racially integrated for years, and attendees felt the song brought black and white organizers closer together. While living in California in the early 1950s, Guy heard the song and was inspired to learn it on guitar. He came to Highlander in 1959 and became music director after Zilphia passed away. “We Shall Overcome” caught like wildfire and was sung in protests throughout the South.

Guy and Candie brought their guitars and spent time with us in the evening, singing and telling stories. They spoke of the textile union organizers who came through Highlander in the late 1930s and helped launch an enormous strike that shut down North Carolina’s entire textile industry. Between 300,000 and 500,000 workers from the Deep South to New England were on strike within a week. The United Textile Workers union membership went up tenfold to 270,000, the largest in the country.

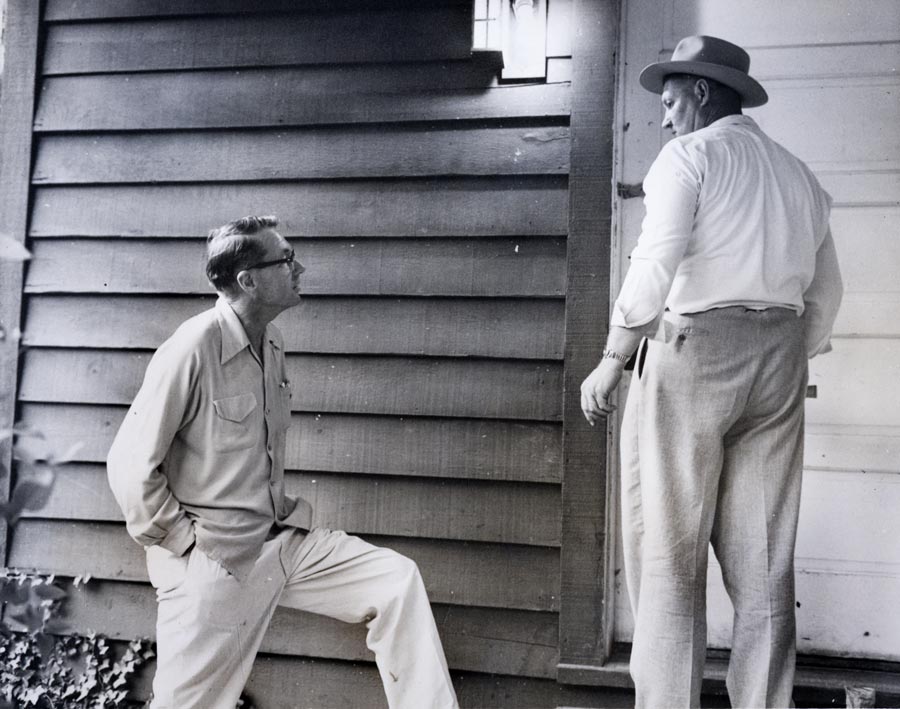

Guy and Candie mentioned, too, the attempts to thwart Highlander’s influence. In 1959, Highlander was raided, and the Tennessee state legislature ordered the district attorney to shut down Highlander, then located in Monteagle, Tenn., for holding interracial classes and serving beer. By 1961, the charge for interracial classes was dropped, but the courts revoked the school’s charter on charges of selling alcohol and that cofounder Myles Horton was personally profiting (a trumped up charge). The local sheriff padlocked Highlander’s doors, and all of its property and land were confiscated. The school quickly rechartered as the Highlander Research and Education Center and moved to Knoxville. But the harassment and hate crimes didn’t stop. The Knoxville News Sentinel reports that, in 1963, “Blount County deputies raided an integrated summer youth camp in Townsend organized by Highlander staff,” and when Myles went to “meet an attorney about the raid, a stranger clubbed him into unconsciousness.” In 1966, two firebombs were thrown through the center’s windows.

(Co-founder Myles Horton watches a local sheriff padlock Highlander in 1961)

From sunup to late in the evening, our group of Teamster organizers would discuss how to build power at Overnite’s various trucking terminals in spite of not having a union contract. We were joined by Rev. Jim Sessions, Highlander’s executive director (who had led Appalachian religious communities to join the 1988 – 1989 United Mine Workers Union strike and an occupation of a coal processing plant in Pittston, Pa., lasting more than six months), and Alice and Staughton Lynd, editors of the 1973 Rank and File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers. We discussed strategies to get difficult terminal managers fired. We discussed how to bring fearful workers into the union. Most importantly, we acknowledged that organizing is a process that takes time, education and agitation — until we win.

We also attended workshops on civil disobedience led by Philip Berrigan, the former Roman Catholic priest and leading voice of the 1960s peace movement. Coincidentally, Berrigan was in the federal penitentiary at Lewisburg, Pa., at the same time that Jimmy Hoffa, a labor union leader who became president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, was incarcerated. Berrigan recalled that the prison guards would regularly bully Hoffa, and so he befriended Hoffa while they served out their respective sentences.

Berrigan taught us how to prevent violent confrontations with police, and the difference between voluntary arrest and resisting arrest. He had gone to jail numerous times for Vietnam War protests, and, in 1980, as a leader of the anti-nuclear, Christian pacifist Plowshares Movement, did jail time for sneaking into a General Electric plant, pouring blood over documents, and damaging components of nuclear warheads by banging on them with hammers (an allusion to the Book of Isaiah, “beat their swords into plowshares”).

We Teamsters learned perhaps one of our most important lessons from the legacy of Highlander’s cofounder and “radical hillbilly” educator Myles Horton, who mentored scores of organizers and died in 1990. His work taught us the importance of listening — not lecturing or trying to sell an idea — to bring workers into a conversation about change, and to create excitement and enthusiasm through democratic participation. He maintained that people are creative, if given the chance to participate and make a difference.

Creativity was key in our organizing campaign: direct action at multiple worksites on multiple fronts, wildcat unfair labor practice strikes, grievance strikes.

So, the following summer of 1999, we ran a series of wildcat strikes at Overnite terminals across the country. We leaked false information to Overnite about where the next strike would occur. When Overnite moved cargo to what they thought was a safe location, we would strike that terminal and walk out. Through organized action, we created chaos and confusion for the bosses.

Highlander inspired us to keep fighting for these workers, to never give up. After decades of Teamster organizing attempts, and a later unsuccessful systemwide strike, UPS (whose workers are members of the Teamsters) acquired Overnite; its workers are now represented by the union.

(The Overnite Teamsters, including Philip Berrigan, Rev. Jim Sessions, Alice and Staughton Lynd, and Guy and Candie Carawan, gather at Highlander in 1998)

We don’t know who exactly is behind this most recent attack on Highlander; an investigation is ongoing. We do know that it reflects the growing white nationalist movements across the country and around the world.

When Highlander’s doors were padlocked back in 1961 for its role in the civil rights movement, Myles laughed and said, “You can’t padlock an idea.”

How right he is. For every warehouse worker and truck driver and unorganized worker who seeks a better life, one free from drudgery, humiliation and low pay, the ideals of Highlander will remain an inspiration and a powerful force for democracy and social justice.

This article was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.