Lessons from the Original War on Coal: Class Conflict and the Fossil Economy

Dayton Martindale

John R. Leifchild, author of Our Coal and Our Coal-Pits; The People in Them, and the Scenes Around Them, saw in that unassuming black rock the underpinnings of mid-19th century Britain’s economy:

But could they filch our mines of coal

They’d steal our bodies, selves, and soul.

‘Tis COAL that makes our Britain great,

Upholds our commerce and our state.

He was one of many from that period to celebrate the virtues of coal — and the steam engine it powered — in prose and poetry.

Today, of course, most of us are less enamored with coal. Miners still count on it for work — and for damage to their lungs. Smog is a severe public health threat in many areas, particularly large Chinese cities. Most prominently, the specter of climate change hangs over all of us, largely driven by carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of coal.

In Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming, Andreas Malm seeks to determine how and why coal came to uphold “our commerce and our state.” This is not merely an academic exercise: Malm hopes the early days of fossil power might provide some clues as to how the coal industry became the destructive behemoth it is today. If we know how the fossil economy came into being, he suggests, we might be better prepared to end it.

The conventional explanation for coal’s ascension, as Malm presents it, rests on classical economists like David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus and Adam Smith: An increasing population combined with physical constraints on the land meant that only technological advance could sustain economic growth.

Early 19th century coal miners. (Photo: Kansas Historical Society)

A more contemporary take is what he calls the “Anthropocene” narrative, referring to the notion, now common in the environmental sciences, that human activity has pushed Earth into a new geological epoch. If humanity writ large is framed as the problem, then the explanation often becomes biological, not social or cultural. Malm cites geographers, literary theorists and others who attribute the rise of fossil fuels and accompanying ecological destruction to some fatal tendency in human nature. Some argue our species’ proclivity for destruction has been inevitable since our ancestors mastered fire.

Marx, for his part, had theorized that technological change drove social relations, not the other way around: “The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist.”

These pictures, Malm argues, rely on some combination of factors to hold true: industry at the time must have been held back by environmental scarcity; steam power must have been more efficient than its predecessors, and thus the more rational choice; the transition must have been embraced by wide swathes of society across the globe, and its benefits shared by the species at large.

None of these, according to Malm, is backed up by the historical record. Instead, he argues the transition to steam power was motivated by the ability to control labor. Thermodynamic power and social power are linked: “the power derived from fossil fuels was dual in meaning and nature from the very start,” he (Malm) writes.

(Image: Yagi Studio / Getty Images)

The book might at times be overly harsh towards the classical economists and the Anthropocenists, often reducing their arguments to their most simplistic form, where they are quite easily torn apart. For example, his critique of the Anthropocene concept (summarized in a March 2015 Jacobin article) ignores the myriad ecological disruptions beyond those caused by fossil fuel combustion, some of which predate or exist outside of conventional labor-capital relations. His critique might still prove to be valid, but as it stands it is incomplete.

But even if he is unfair, this does not take away from his central thesis: His thorough account of the switch to steam shows quite convincingly that coal did not make Britain great for everyone, and the transition was rooted not in technological superiority or environmental scarcity but in good old fashioned class conflict.

Time, space and labor

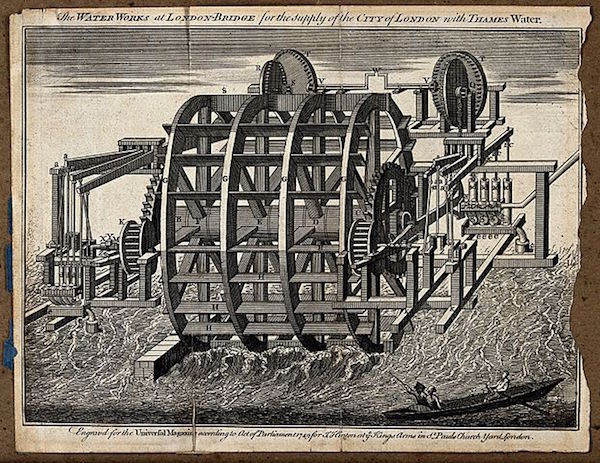

Most of the book takes place in 19th century Britain, where James Watt’s steam engine competes with water wheels to be the primary power source for cotton mills. Malm sets this up as a battle between “flow” — running water, accessible to all and inexhaustible — and “stock” — coal, which is finite and must be dug up.

At the outset, this wasn’t much of a competition: water was significantly cheaper and real estate along rivers remained plentiful.

A water wheel on the river Thames. (Image: Wikipedia)

But there were two major problems; time and space.

First, water was inconsistent: Floods or droughts could constrain when the mill could operate. This had long been a part of doing business, and mill owners had a simple strategy to deal with it. To make up for lost time, laborers would be made to work overtime.

Steam power changed the game — it could be steady and constant, running for precisely as long as you wanted it to. But that might not have been enough if it weren’t for changes in labor laws, brought about not through the vote (the working classes did not yet have that) but through militancy and strike. Limits were eventually placed on how long one could be forced to work per day, which made it more difficult for mills to catch up after setbacks.

An Edward Goodall (1795−1870) engraving, commissioned by Queen Victoria in 1852, depicts a changing landscape. (Print collection of Maggie Land Balnck)

Mechanic Robert Thom devised a strategy — a system of dams, reservoirs, aqueducts and sluices — to overcome the river’s temperament, to keep the flow steady and dependable across a given region. Where implemented, his system was successful, but it failed to take off. Here the villain was not labor but the obstinacy of the mill owners themselves.

Thom’s complex designs required shared initial investments, yet the mills farther down the river would benefit less. His system was still cheaper than steam, but owners often found themselves unable or unwilling to cooperate.

Another drawback of waterwheels is the obvious fact that they must remain along rivers. Coal was by nature more mobile, but again, this would not have become such an advantage if it weren’t for the volatile labor unrest.

As Britain’s population — and thus its labor force — grew more concentrated in a few urban centers, these centers became attractive places to set up a cotton mill. In rural sites, labor was scarce, and housing, schools and churches had to be built from the ground up, generally at the mill owner’s expense. And crucially, in this time of economic crisis and labor unrest, rural areas offered no ready supply of strikebreakers.

The opposite was true in cities, which came ready with infrastructure and people looking for work. Fear of the working classes was rampant among the propertied, and the steam engine offered a means of control.

[If you like what you are reading, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the wolf on the upper right of your screen.]

And while Malm could have explored this idea more fully, he hints that the steam engine also allowed for a break with the physical nonhuman world, from seasonal cycles and the contours of the landscape itself. Coal does not dry up in drought or flood the factory in heavy rains. A steam engine can run faster or slower at the boss’s discretion, and steam-powered mills need not be built along a riverbank.

Coal may be a physical object that must be mined and transported, but it lacks the autonomy of a river. This was not lost on the mill owners of the day, and allowed them to enforce more regular and regimented work hours, and to build up urban centers divorced from the rural terrain. The conquest of human labor went hand in hand with the conquest of the nonhuman world, with liberation from uncontrollable ecological processes.

Nature out of fashion

The capitalists knew precisely that they had steam to thank for their emergence from the economic crisis, while labor knew they had steam to blame.

As men like Leifchild sang the praises of coal, the workers’ paper Northern Star saw things differently: “So far from the discovery of Watt being an unmixed good, it has been to millions an unmixed evil.” Malm writes that steam was “fetishized” by the capitalists, but “demonized” by workers.

They called it “a ruthless King,” “a tyrant fell;” they wrote dystopian fiction in which “vegetable nature had ceased to exist,” “animal life appeared to be extinct,” “Nature was out of fashion,” all because steam-powered machines now filled the world, blacking out the sun with smoke.

Friedrich Engels observed that workers “are drawn into the large cities where they breathe a poorer atmosphere than in the country.” The steam engine raised the temperature inside of factories, and prophetic themes of air pollution and heat were common in worker writing.

The most militant labor uprisings targeted steam engines, incapacitating them to bring industry to a halt. Amidst the riots, an anonymous placard directed workers; “Stop getting Coal, for Coal supports the money-mongering Capitalists.”

Sustainability and political will

Despite these protests, coal power won out and became an integral part of economic expansion in Britain and elsewhere. In the United States, as Malm documents, urbanization occurred later in the 19th century, and was likewise followed by a turn to the steam engine.

Today, as many developed countries switch to gas or renewables, China has become the new “chimney of the world,” writes Malm. Coal power blossomed in China largely because foreign corporations took their manufacturing there, primarily motivated not by cheap, plentiful energy but by cheap, plentiful labor. Once again, he argues, the desire for controllable workers has led to an increasingly fossilized economy.

According to a World Bank study, only one percent of China’s 560 million city dwellers breath air considered safe by European Union standards. (Photo: Leo Fung / Flickr)

The blame is not all China’s. Malm makes the point — too often ignored in contemporary climate discourse — that while China may be the largest emitter, much of those emissions are from manufacturing worthless nonsense that is then exported to developed nations. The United States and Europe, which now import goods from China (and other coal-powered countries with lax labor standards), can limit their manufacturing and start to look like they’re getting a handle on emissions. Meanwhile China is framed as the climate culprit, and their people suffocate in smog. The West offshores far more than just jobs.

Malm sees history repeating itself elsewhere: Sun and wind fit the “flow” profile of water, and many of the same arguments for and against apply. Light and air are our commons, and thus difficult to profit from, despite or because of their ubiquity. Their power can be intermittent, less constant than fossil fuels. The large-scale renewable energy projects that might provide something steadier are difficult to organize, evoking the inter-capitalist squabbling over Thom’s sluice schemes.

Malm discusses decentralized local energy production and large-scale planning as potential solutions. While he finds the latter more plausible, both would require a change in values. If the primacy of fossil fuels is rooted in power over labor and disjuncture from the rest of the Earth system, then its solution might be something a little more communal, less beholden to the ethos of competition.

Specifically, he offers the work of Stanford researcher Mark Jacobson and UC Davis researcher Mark Delucchi to show that with enough effort, a fully renewable global energy system is possible — what’s needed is political will.

Through the goods we buy — the cars we drive, the planes we fly — we are deeply connected to the fossil economy, he argues, and that connection is reinforced with every purchase. But the benefits are distributed disproportionately, shared mostly by the largest consumers and those shareholders and executives who reap the profits. The rest of us, Malm points out, the vast majority, are not tied to the status quo in the same way, and in fact stand to suffer greatly should climate change continue to intensify.

He has no blueprint for achieving the necessary political change — perhaps that would be asking too much. But it’s clear to me that we no longer live in the Britain of 1842. The Fight for $15 may be rejuvenating America’s labor movement, but there are no general strikes against fossil fuels, no marching workers disabling steam engines. Those employed by the coal industry are skeptical of the transition to renewables, worried it could cost them their livelihoods.

Yet there is grounds for hope. Diverse coalitions — including working people, labor groups and (increasingly) entire communities—have sprung up to block pipelines, arctic drilling and other expansions of fossil fuel infrastructure. And to those justifiably skeptical, the case can be made that tearing down that infrastructure and building a new one, the necessary task we have ahead of us, is going to take a lot of work.

So Malm leaves us with an injunction — one borrowed from rioting laborers of nearly two centuries ago, laborers who nearly stopped the fossil economy before it even began: “Go and stop the smoke!”

Dayton Martindale is a freelance writer and former associate editor at In These Times. His work has also appeared in Boston Review, Earth Island Journal, Harbinger and The Next System Project. Follow him on Twitter: @DaytonRMartind.