On April 3, Joseph Medicine Crow — Native American historian, anthropologist, author and World War 2 veteran — died at the age of 102 in Billings, Mont.

Medicine Crow was born on the Crow Indian Reservation near Lodge Grass, Mont., and spent most of his life there (with the exception of his time fighting Nazis in Europe with war paint and an eagle feather under his allied forces uniform). His memory was exceptional and he could recount the oral history of his people that he was exposed to as a child.

He could recall in vivid detail the firsthand account of the Battle of Little Big Horn (Custer’s Last Stand) as told to him by his great-uncle and Medicine Crow continued to lecture on the battle well into his nineties. Today, 140 years after the Battle of the Little Big Horn and 126 years after the related Wounded Knee Massacre, remembering this history remains central to Native American demands for justice from the United States.

Background

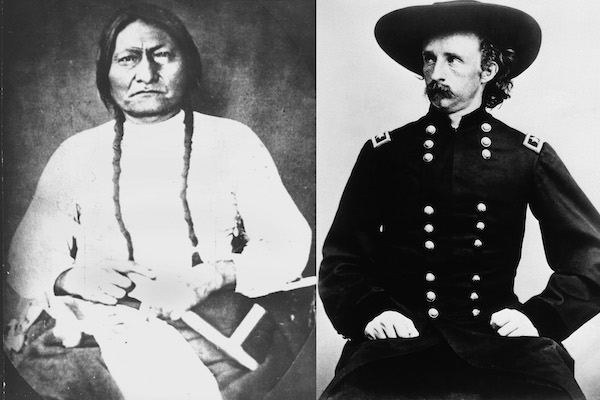

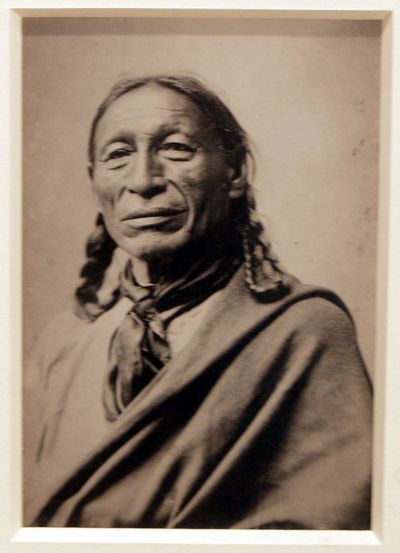

On June 25, 1876, at the Battle of Little Big Horn, a band of Sioux followed Chief Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse in a charge against General Custer and the Seventh Cavalry. In the dominant settler-colonial discourse this came to be known as Custer’s Last Stand. The Lakota referred to the conflict as the Battle of Greasy Grass. Dewey “Iron Hail” Beard, a Lakota Native, fought against the cavalry and, many years later, became the oldest known Lakota survivor.

Chief Sitting Bull and General George Custer. (Photo: wbur.org)

Beard was also present when the Seventh Calvary sought revenge for its historic defeat. On Dec. 29, 1890, 14 days after the U.S. Army arrested and murdered Chief Sitting Bull, General Nelson Miles commanded Major Samuel Whiteside and his itchy cavalry to attack Chief Spotted Elk’s band of 350 Minneconjou Lakota Sioux. This resulted in the death of about 200 Lakota men, women and children, a slaughter that became known as the Wounded Knee Massacre.

Dewey Beard (also known as Wasú Máza or “Iron Hail”) 1858-1955. (Photo: ameritribes.com)

[If you like what you are reading, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the bear on the upper right of your screen.]

This is an excerpt from Surviving Wounded Knee: The Lakotas and the Politics of Memory by David W. Grua.

On November 2, 1955, Dewey Beard passed away quietly in his sleep on the Pine Ridge Reservation, just a few years shy of his one hundredth birthday. He was well enough known at the time of his death that the New York Times published his obituary, describing him as “the last surviving Sioux Indian who fought at the Little Big Horn, better known as Custer’s Last Stand.” The paper also reported that Beard had survived Wounded Knee, “one of the last engagements between whites and Indians in 1890. His family was wiped out and Mr. Beard was wounded.” However, the nation’s newspaper of record failed to mention the third major struggle for which he was known. Like many victims of traumatic events, the memories of Wounded Knee surfaced on a regular basis during subsequent years. More than a quarter century after Wounded Knee, Beard stated: “Every time I recall this history, the matter is so vivid in my mind, that it seems to me as though it had happened just yesterday.” In 1938, Beard uttered a simple yet profound statement to a congressman asking him about Wounded Knee: “If I was killed at that time [in 1890], I would not be here testifying for my people.” For more than half a century, Beard had been a survivor, testifying to anyone who would listen of the sufferings inflicted upon his people at Wounded Knee. …

Beard had dedicated his life as a survivor to testify to what had happened at Wounded Knee, an obligation he no doubt felt toward his wife, newborn son, mother, father, brothers, niece, and other relatives whose lives had been claimed in that massacre. He also felt an obligation to the dozens of survivors who struggled to articulate in words the trauma that had shattered their lives on December 29, 1890. Although Beard never learned to speak or write English, he nevertheless found ways to speak Lakota to individuals who heard, translated, and recorded his words on paper, a medium that could share a form of his memories that could influence others who never met or spoke with him. …

Aside from dictating their memories of sympathetic whites, Beard and the survivors created memorial traditions at Wounded Knee that ensured it would become a place of memory that was recognizable even outside of the Lakota community. Because Wounded Knee occurred within the boundaries of the Pine Ridge Reservation, the survivors had some control over how the site would be interpreted. Joseph Horn Cloud’s monument explicitly identified the mass grave as the resting place of innocent men, women, and children massacred by the Seventh Cavalry. The survivors’ regular commemoration at the site signaled to others the importance of the place. Native intellectual Vine Deloria, for example, later recalled that “the most memorable event of [his] early childhood [in the 1930s] was visiting Wounded Knee.” He also remembered that the Lakotas revered the survivors, including, undoubtedly, Dewey Beard. …

For decades, the survivors had testified to the suffering inflicted upon their people at Wounded Knee. In accordance with traditional values, they asked the government to compensate them for the wrong committed against them that violated the solemn treaty obligations. Ultimately, the survivors demonstrated that the Indian Wars had not ended in 1890; rather, the venue of struggle had changed from the battle field to the landscape of memory. Although the United Sates never compensated the Lakotas for their losses at Wounded Knee, the survivors’ unyielding pursuit of justice left an imprint on the American memorial landscape that continues to reverberate 125 years later.

Excerpt from Surviving Wounded Knee: The Lakotas and the Politics of Memory. Oxford University Press, 2016. Copyright © 2016. Reprinted with permission.