“Believe it or not I care” is a Management and Training Corporation (MTC) company slogan on display at Willacy County Correctional Center in Raymondville, Texas. But a new report by the ACLU is calling that slogan into question. Last summer, 30 prisoners at the facility were placed in isolation units “for refusing to leave the recreation yard and return to their dormitories after prison officials ignored their complaints of toilets overflowing with raw sewage,” according to the report.

The report calls Willacy “a physical symbol of everything that is wrong with enriching the private prison industry and criminalizing immigration.” Nearly 3,000 so-called “criminal aliens” are locked up in the privately run facility, one of 13 “Criminal Alien Requirement” (CAR) prisons in the United States. Managed by private companies on behalf of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the facilities are mostly used to hold low-security non-U.S. citizens convicted of immigration offenses or drug-related crimes.

“Warehoused and Forgotten: Immigrants Trapped in Our Shadow Private-Prison System,” the result of several years of investigation into five CAR prisons in Texas, describes overcrowded facilities, inadequate medical care and widespread use of solitary confinement.

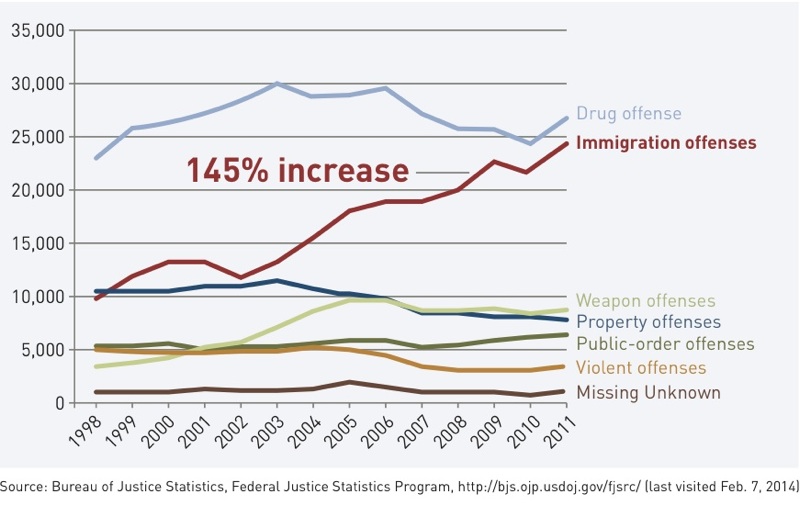

According to one of the report’s authors, Carl Takei, CAR prisons have “mushroomed” in recent years as a result of a massive increase in prosecutions for illegal entry or re-entry. “This is an offense that until about 10 years ago was very rarely charged and now is one of the most charged offences in the federal judicial system,” says Takei.

While federal prisons are supposed to follow American Bar Association standards, researchers “uncovered evidence that the CAR prisons use extreme isolation in ways that are inconsistent with the ABA Standards and BOP policy.” The report alleges that prisoners were isolated in Special Housing Units (SHU) for “minor infractions or even for requesting new shoes or extra food.”

The Federal Bureau of Prisons declined to comment on specific allegations in the ACLU report, but in response to an email from The Prison Complex, Chris Burke, a public affairs specialist at the agency, defended the use of private companies, calling the practice “an effective means of managing low-security, specialized populations.”

Prisoners entering federal prison 1998-2011 by offense (via: ACLU)

CAR prisons have been touted as a way to alleviate some of the severe overcrowding in low-security federal prisons. According to the bureau, last year 85 percent of low-security inmates were “triple bunked or housed in space not originally designed for inmate housing, such as television rooms, open bays, and program space.” Burke says the majority of prisoners in facilities like Willacy County Correctional Center “are sentenced criminal aliens who will be deported upon completion of their sentence. The criminal aliens were an appropriate group for housing in privately operated institutions where there are somewhat fewer programs offered to prepare offenders to successfully reintegrate into U.S. communities.”

More than 25,000 non-US citizens are currently held in CAR prisons. The prisons are some of the few within the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) system that are privately run. But with two more open contracts for thousands of additional CAR beds, private companies have spoken about the opportunity for expansion. The ACLU report quotes a Corrections Corporation of America executive who spoke to an investors’ meeting in 2009:

We believe that the Federal Bureau of Prisons continues to see value in using the private sector to meet their capacity needs and will continue to provide a meaningful opportunity for the industry for the foreseeable future.

While the BOP says privatizing prison management is more efficient, Takei says that putting prisons in the hands of profit-driven companies like CCA, Geo Group and MTC is part of the problem. “Much of the blame for how bad things are lies with the BOP, because they know they are contracting with for-profit companies and yet they are setting up terrible incentives in the contract,” he says.

Among the “incentives” for ill-treatment identified by the report were contractual requirements that the ACLU says “encourage the private prison companies to place excessive numbers of prisoners in isolation.” The report continues, “CCA’s contract for Eden, MTC’s contract for Dalby, and GEO Group’s contracts for Reeves and Big Spring each require at least 10 percent of the “contract beds” to be SHU isolation cells — in effect, setting an arbitrary 10 percent quota for putting prisoners in extreme isolation whenever the prison is filled to capacity.”

Takei calls the high quota of isolation units required in CAR prisons “mystifying,” since, he says, it is almost double the usual number of SHU units in government-managed prisons. He blames the 10 percent quota for the over-use of solitary confinement in the prisons. “When a prison hits 100 percent capacity that means they need to fill all the beds including the isolation beds and that’s what leads to the abuses of isolation,” he says. At Willacy, the report found 300 prisoners were in SHU at any one time.

In the SHU, the noise was bad. People could be heard screaming and kicking their doors all day,” Alex told us. Some prisoners reportedly attempted suicide or self-mutilation. They describe the cells as small, with three metal walls and a metal door. Showers take place outside of the cells and are only available on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. When prisoners are taken out of their cells for their daily hour of recreation, they stand in a small outdoor cage with fencing on the sides and the top.

Takei says the BOP gives other incentives to companies to keep CAR prison cells filled:

The contracts further provide “Incremental Unit Price” payments for each additional prisoner above the 90% occupancy quota, up to 115% capacity. By the terms of the contract, the companies actually make more money by admitting more prisoners from BOP than their facilities were designed to hold.

“Marc,” a CAR prisoner, told ACLU researchers that he was told by a guard at a GEO group-run prison, “When I see you, I see $80 a day.”

BOP public affairs specialist Chris Burke denies that the CAR prisons have been filled over capacity or that his agency has offered incentives to companies to do so. “There is no overcrowding in the BOP’s privately-operated secure adult correctional facilities,” he wrote in an email. He continued, “in most of these facilities the restricted housing beds are not part of the maximum contract amount of 115 percent, so there is no financial incentive to keep these beds filled unnecessarily.”

Asked for a response by The Prison Complex, the ACLU said that while this may be true in the case of new BOP contracts, it does not seem to apply to existing contracts. Takei wrote in an email:

BOP has changed how the isolation quota is calculated in its open CAR solicitation in ways that reduce (though, I would argue, do not eliminate) the perverse incentives to over-use isolation. However, in the contract documents we obtained, we were unable to find similar modifications to existing contracts.

If such modifications do exist, says Takei, then that just goes to show “that BOP needs to be more transparent about its private prison operations.”

While the ACLU report focuses on Texan prisons, other private prisons holding non-U.S. citizens have faced criticism before. In 2012 prisoners rioted at a CCA-run CAR prison in Mississippi. According to the FBI, the riot was a response to poor food and medical care and the view amongst prisoners that they were not respected by the guards. The riot, which left one guard dead and twenty prisoners injured, “suggests that the problems we saw in the Texas prisons are not unique” according to Takei. He says that the ACLU is investigating poor conditions in CAR prisons in Mississippi and Georgia, but, as in Texas, obtaining information from officials about the facilities in those states has been “extremely difficult.”

National CAR map (via ACLU):