A Farm Organizer Visits Fish Country: An Alaska Journal, Part II

Severine Von Tscharner Fleming

Editor’s note: Severine Von Tscharnar Fleming was invited to Alaska to study the commons and speak to young people on behalf of the Alaska Marine Conservation Council and the Alaska Food Policy Council. Part two of her three part report continues here. (Read An Alaska Journal Part I)

What is it about the ruthless sea? An acculturation in agricultural landscapes, full of flower buds, dewdrops, fresh hay, kittens and baby lambs cannot prepare you for the hard, chilling mechanics of a mechanized fish harvest. To my tender agrarian eyes, the fishing business is brutal. We may call them “stewards of the ocean” but lets face it — they are killing fish.

The vessels themselves vary a lot in size — from combine, to dump truck to barn size — with hydraulics overhead and $60,000-plus nets piled up waiting for use. The fish get hauled in and killed by the dozens of tons by hulking large steel vessels — machines out back, overhead, swinging in the air, these vessels barely accommodate the needs of the humans aboard. I think it must be like living inside a cotton gin, with wave-action. This fishery is for real — a harbor full of boats, warehouses, containerized freezers, semis, box trucks and ice machines on such a scale as you cannot imagine. This is no rinky-dink outfit. But then the scale of the landscape (compared to a place like Maine) means that these boats are dwarfed by the harbor they’re moored in, looking like little metal toys.

The average size of a salmon boat, according to the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute, is 37 feet. (Photo: Severine von Tscharner Fleming)

Food management

Regulators working closely with biologists and fish-counters are credited with “managing the resource,” the healthiest salmon runs and fisheries in the world. No one can fish until the fish-counters are satisfied that enough salmon have returned upriver to reproduce. Only then can the fishing begin. Of course, more than the technicians, it’s the unedited landscape that’s to blame for all the fish — vast headwaters of steep sloped forest landscape, the natural wealth of ocean and uplands combine to support this mega-ecosystem. Alaskans evoke “ the resource” frequently in conversation, and express pride in its guardianship. Indeed, one could argue that the ecosystem is optimized for salmon above other species. Each year, the infusion of millions of dollars into state-run smolt (baby salmon) hatcheries yields fertilized eggs by the multimillions that get released into the ecosystem. The manipulation of spawn takes a few forms, from fertilizing ponds to fatten up the zooplankton which feed the baby fish, to notching beaver dams to ensure the returning salmon can get up to their spawning grounds, to elaborate fish ladders across dams and roads that cut up the habitat.

These interventions on behalf of the salmon represent “scientific excellence” and massive public investment in the health and durability of the fishery. But they are by no means “natural.” Just to put the numbers in context, these non-profit hatcheries sell the right to fish the runs they support in order to pay for their own operations. The annual income they’re looking at (according to the brochure I picked up during my slide show there) was $2.9 million. That’s a lot of fish!

Management involves a complex algorithm of stewardship and finance, and one key to its stewardship is that it’s shielded from global plunder. Until the Magnuson-Stevens Act of 1976, foreign vessels fished off the coast of Alaska with hardly any oversight or restraint. In the 1950s, the threat to their fisheries gave Alaskans incentive to fight for statehood in order to protect themselves from plunder, and this legislation created a framework and mandate to manage for “sustainable yield.” It makes sense that a nation of our scale would create boundaries and structural efforts to ensure our access to one of the worlds most nutritious foods — the wild salmon. And the anadromous fishery has been protected and adjudicated for our public benefit by decades of litigation between various constituencies, natives, rural populations, subsistence fishers and sports fishers.

The labor

Fish processing is wet, cold-fingered work. Filleting, gutting, washing, packing, vacuum sealing. The suck pop sound of a freezer door lurched open, aluminum casters, the slap of fish-heads into the slop bucket, hot hooded teenagers with curved knifes, show-off physicality and scrawly handwriting. The water in the harbor is misty, with oily sheen, filaments of dead algae and paint flakes. A kiosk shows “learning videos” about ocean acidification.

The state seafood industry contributes 78,500 jobs to the Alaskan economy and an estimated $5.8 billion annually. (Photo: Severine von Tscharner Fleming)

This seems like a crucial moment to get involved with the culture and engage the idioms and attitudes of these young guys on the fish scene. Their attitudes, entitlement, conservation ethic, knowledge of the habitat, fish-size baselines and expectations of remuneration all constitute a dockside culture. Do they have the attitude of debt, diesel and a fat payday — like those boom-town, high-school lobstermen in Maine? Is it the machismo of a “Most Dangerous Job” like the Bering Sea crabbers, tumbled on the biggest seas? Is it a bit like a rodeo, where the manliness and scenery conspire to keep labor costs low, and young blood flooding in the gates? These are questions I cannot definitively answer — but it seems so.

The Pebble Mine

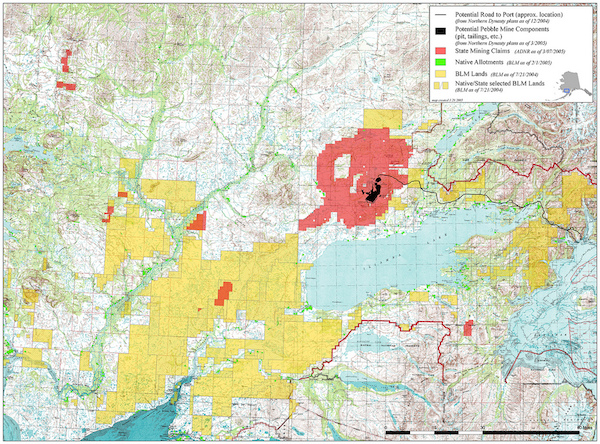

Right in the glorious headwater armpit of a peninsula that casts its scatter far out into the Bering Bea lies a massive, poisonous pocket of gold. This is one of the largest “plays” in the world of gold, copper and molybdenum (a highly sought after metal used in making electronics). In a story that feels like a Batman cartoon, Pebble Mine is backed by incredible hulks of international finance: Anglo American and Northern Dynasty. These companies, who are among the largest mining concerns in the world, want to build one of the largest mines in the world in the great (and one of the last) remaining Salmon runs of the world. Thus far the battle to stop Pebble Mine has waged for more than 8 years — galvanizing environmentalists, salmon fishermen and recreational users, most of whom live in the rich ecosystem.

Map of the proposed Pebble Mine. (Image: Flickr)

Boreal experiment station

One of the talks I gave was 36 miles north of Anchorage, in Palmer, at the loading dock/processing area of the Matanuska Experiment Farm. Flanked by an underground rabbits warren of potato storage caves, with experimental crops carefully selected for the food bank, it was a facility built for many dozens of state-paid workers. The proud officialdom of framed notices and government posters in the long hallway fed into large but abandoned-smelling classrooms and soil testing labs, with equipment from the 1980s and earlier. The experiment station is mostly moribund now, the equipment — vehicles, heated greenhouses, barns, warehouses of grain/potato equipment, tractors and tillage implements — all dormant. It’s capably and lovingly stewarded by a skeleton crew who oversee trials of the indigenous superfood rhodiola and a large collection of rhubarb varieties from around the world. Given our changing climate, it seems like these kinds of facilities could play a part in experimental cropping systems— learning ahead of the curve what crops will grow in our northernmost latitudes, places many climate scientists think will soon see new relevance as productive ecosystems.

A child has a look around the the Matanuska Experiment Farm, part of the Agriculture & Forestry Experiment Station. (Photo: Severine von Tscharner Fleming)

Living the subsistence dream

Far up-river in the Mantanuska Valley, in the Chickaloon Valley, I vistited former high-altitude trekker, avalanche expert and homestead farmer, Allie Barker at Chugach Farm. Allie runs a market garden with pigs and chickens — all off grid. She sells pickles at markets in Anchorage, and preserves a cave-full of self-sufficiency supplies including canned salmon, sauerkraut, fermented blueberries, honey, canned moose, squashes and storage cabbages. She and her partner live off the land — wild and domesticated — the subsistence dream. As I came to visit, she was launching her partner Jed off into the river in an inflatable boat to hunt moose. Here, in the uplands of Alaska’s most agricultural valley, they are fighting one of the largest coal mining companies in the world, trying to raise awareness that the open pit coal mine would blow dust on the best ground for Alaskan food security. Clearly, the commons needs more defenders.

Allie Barker and Jed Workman on Chugach Farm. (Photo: spenardsfarmersmarket.org)

Looking toward our future

On land, we’re learning more and more about landscape recovery, restoration, scar tissue and residual toxicity. We’re learning that natural capital, when diminished by extraction, undergoes fundamental changes that reduce complexity and biological potential, often for decades or scores of decades. We can see how rebounding happens, some places slowly, some more quickly.

In the young farmers movement, more and more of us are entering the field with reform on our minds, with an aim to heal land, restore wild-lands, and reclaim a better balance between the domestic and self-willed ecosystems. I wonder if the incoming generation of young fisherman, could team up with the markets we’ve created — if they can adequately articulate their conservation ethic to the marketplace, and whether direct sales, new economic models and ecologically based evaluation of fish-harvest can give these players a fair-deal in the marketplace. Could every CSA in the lower 48-Greenhorns network make connection with a community fishery, and help distribute fish at a fair price and large-enough volume to our already dedicated consumers?

[If you like what you are reading, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the wolf on the upper right of your screen.]

Land and sea share the commons of ecosystem as a foundation. We think of land as private and water as public, but in fact more than one-quarter of U.S. acreage is public land, and increasingly the ocean floor, the right to fish and even the seaweed growing on the wild shore are becoming privatized. Confronting the common conundrum of land access, has made me a student of the commons and its management.

The callus-like shapes extractive capitalism can inspire

Alaska’s license plates say “the last frontier.” Frontier suggests the edge of civilization, and the beginning of the wild-lands. Frontier economies have their own peculiar logic and lifeway — lumber camps, mine camps, boomtowns — in Alaska’s case this is dominated by petroleum. With antlers stacked in hip-high heaps besides the hastily built cabins and sheds, it felt like every single road we traveled was getting widened or repaved, and every single farmer we met was fighting a mine project. This is the fishery that inspired statehood and carved out sovereignty in a 200-mile zone around the splayed coastline exclusively for U.S. fishing interests. Alaska, as an icon of wilderness, seems like a large, white-capped capillary of resource exchange. Most of what makes the economy tick and tock, is what gets flown, shipped, piped and pumped out of here.

A farmer in the field. (Photo: Severine von Tscharner Fleming)

Economy and Ecology

Anchorage is a mighty big city. “Eat wild fish!” read the billboards and yet, in the supermarkets here there is shrimp from Mexico, farmed fish from Chile and not much in the way of local vegetables. It’s very clear that this economy is built on resource extraction. Settlement patterns reflect the distortion. The majority of food eaten in Alaska is flown or barged in from the lower 48 and delivered to remote areas by bush plane. Most places settled by humans before the age of petroleum have a structure that doesn’t require it quite so dramatically. As a result of the energy-seeking economy, there are hardly any farms here relative to population. Indeed, most of the terrain is hardly habitable for a land-based economy, except for this extreme import-driven supply chain that’s justified by mining.

Older places, in terms of human settlement, are usually those oriented around fishing and farming communities. These places and geographies often make more ecological sense in many ways — harbors become ports, mountains become headwaters, rivers become corridors of trade. These kinds of places also make more sense from the perspective of an agrarian democracy. Strange bedfellows join in alliance against a toxic mine. But what logic of conservation can work in a tumbling cascade of biological and ecological systems whose members have neither votes, nor dollars, nor lobbyists?

(To read an Alaska Journal Part III, click here)