Organizing with Klansmen for Social Justice: Bob Zellner Tells His Story

Shailly Gupta Barnes

Bob Zellner is a veteran of the Civil Rights movement. He grew up in rural Alabama, the son and grandson of Ku Klux Klan members and ministers. When Bob was a kid, his father took the dangerous step of renouncing his Klan membership. The decision had a profound effect on Bob, who went on to be the first white field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Mississippi. After SNCC became an all-black organization Bob joined the staff of SCEF, the Southern Conference Educational Fund. With Anne Braden, Dottie Zellner and others, Bob founded the GROW Project (Grass Roots Organizing Work aka Get Rid of Wallace).

Today, Bob plays an important role in North Carolina’s Forward Together Moral Movement, mentoring young leaders and drawing on decades of experience to help guide the effort. He’s also been a major force, along with Mayor Adam O’Neal of Belhaven, N.C., behind The Walk from NC to DC to save rural hospitals.

In his more than 50 years of organizing with the poor in Mississippi, Alabama and across the South, Bob faced considerable challenges to his work of bridging entrenched racism and prejudice. This came in multiple forms, including brutal confrontations with the Ku Klux Klan as well as dealing with the skepticism of progressives who doubted whether the racism of poor white southerners could ever be overcome. Bob addressed these challenges by showing what was, in fact, possible when people were given the opportunity to work together towards something bigger than what they were ever told was possible.

Earlier this year, I spoke with Bob about his own history, the work around rural hospitals and the effort to build a new Poor People’s Campaign for Today. This is the first part of my interview. The second will be published tomorrow. (Note: The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Why did you get involved with the Civil Rights movement and poor people’s organizing?

All through my life a lot of people would read my name, they would assume that I’m from New York, I’m a Jew and so on, not knowing that my Daddy’s a Methodist preacher and a member of the Klan. There’s not a lot of Jewish people who are members of the Klan. All through my Civil Rights career, people would say to me: “Why did you go South to help the Black people?” And I would say “Wrong, moose breath! Number one, I didn’t go South, I was already there. Number two, I didn’t do anything to help the Black people, I hope what I did helped Black people, but I got involved because I was not free. I was not free.

What was it like when you first became involved in the Civil Rights movement?

The Ku Klux Klan captured me at the first demonstration I was ever in — in McComb, Mississippi — they almost killed me that day. They beat me, really really bad, and I thought they were going to kill me in the street. And then they took me inside, and then later on they turned me over to the mob. And the mob had hangman’s nooses. They intended to lynch me and the other protesters.. They said, “We’re going to hang you with this rope from that limb right there.” And of course, being a sociologist, I began to get outside my body and think about what’s happening here. And the first thing I thought was, “This is my first demonstration. These people are over reacting! This is my first day out, and they’re going to hang me.”

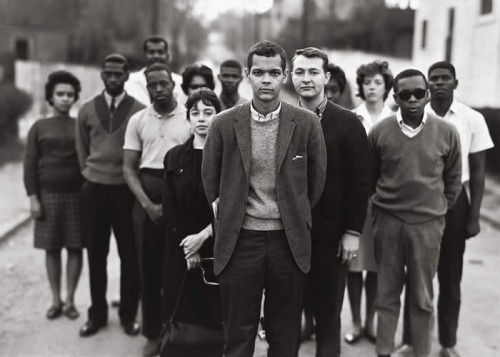

Bob Zellner stands to the right of Julian Bond (center) in the early days of SNCC. (Photo: Kairos Center)

What was it like, later on, organizing with poor white communities in Mississippi, as part of an effort to build relationships across color lines?

We were organizing in Mississippi at the same time that Dr. King was murdered. Our project was called GROW — Grassroots Organizing Work, and Get Rid of Wallace. And we were going into the areas that were particularly strong Klan strongholds. When people used to tell SNCC, “You can’t organize in Mississippi,” SNCC would say, “Okay, that’s where we’re going, we’re going to Mississippi, because yes we can organize there and we’ve got to take this terror of lynching away from the enemy. We’re not afraid, we know that we may die, but we’re going to go ahead and do it anyway.”

So what we started to do was to work with, first of all, the very poor people in the Delta that Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer had worked with for years. A lot of very poor white people in the Delta had come to the Head Start programs to get jobs and also to have their kids have the benefit of the education. Mrs. Hamer was the first person — a Black Mississippian sharecropper — who helped launch the white people’s organizing project in Mississippi. So we were working with her, and she says to us, “Well a lot of these people you have to work with them on a material basis: They need a job, and they need their kids to be taken care of. And so whatever they feel about race, that’s secondary to whatever they need.” We extrapolated that to, if people need a good union, a good strong union, they’re going to have to work Black and white together to get that.

The theory was that racism is very high up on the value system of a lot of white Southerners, but it’s not always at the top. Maybe a strong union or a good education or better income and stuff might trump their racism.

So what did GROW do to get started?

We started in the Mississippi Delta and we eventually came to the conclusion that the people that Mrs. Hamer was working with were so poor and so far down that they needed social work, and we were in a little bit of danger of slipping into a social work organization. And we didn’t intend to do social work. We had to do a certain amount of it, just to get our organizing done, but we understood that we needed to get to where the working people were because they had an organizational structure.

One of the workers was M.O. McCarty. McCarty was a worker in the plant, a member of the union, and a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as a lot of them were. But he was a militant trade union guy, so were able to start working with him and some of the other Klan people on the basis of being trade unionists.

What was it like organizing with Klan members? How did they respond to the GROW project?

We made it very clear from the very beginning — GROW stands for Grassroots Organizing Work and it also means Get Rid of Wallace — and we opposed the Klan method of separating workers. We’d say, “You may be a Klansman, you may be a racist, but if you want a union and you want GROW project to work with you, you need to understand that we’re from SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, we’re from SCEF, the Southern Conference Educational Fund.” And they knew these organizations. SCEF was on billboards in the South — pictures of Martin Luther King, Myles Horton, Aubrey Williams and others, pictures of all the people that we knew were on these billboards that said: “Communist Training School, Highlander Folk School.” We said we all associate with the Highlander Folk School, and if you work with us the FBI’s going to come and tell you that we’re dangerous Communists.

And I said, “I’ve been arrested for criminal anarchy. I’ve been arrested under the John Brown statute for insurrection.” So the old Klansmen would hit the table and say, “You think you’re the only one being messed over by the FBI? They follow us all the time! You think you’re the only one that’s been charged with shit? We’ve been charged with everything too!” So we began to form a kind of camaraderie around that.

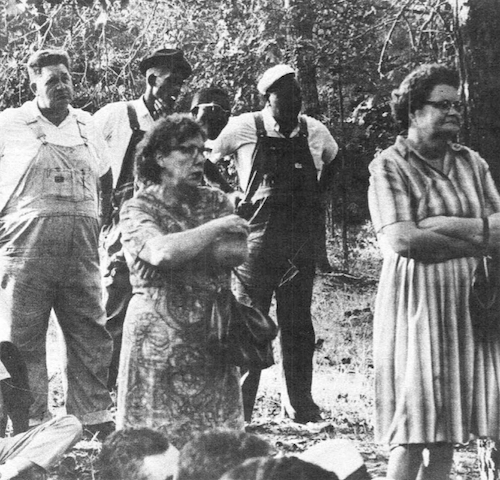

The GROW project meets in Laurel, Miss. (Photo: Kairos Center)

How did this relationship change as you began working together?

I’m just going to tell you about M.O. McCarty. He started having me come stay with him at his house all the time and one night he said, “Bob, you know I was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.” He said, “I still go to meetings, but I’m not with them anymore.” And he showed me his arsenal, the most brutal arsenal of weapons, home-made weapons, all kinds of stuff that you can imagine. I mean he wanted me to know for sure, since he was going through a transition, he wanted me to know for sure how bad he, M.O. McCarty, had been.

And Walter Collins was one of our few African American staff people. This was the time of Black Power, SNCC had become all Black. But we couldn’t do the organizing project of GROW, which had been presented as a SNCC project, if we were organizing white people just as white people. We said: “We have to organize in an interracial way. \We’re going to have to have an interracial staff.” Walter Collins was a member of the New Republic of Africa, so he was a very militant dude. But he saw the necessity of working with poor white people.

And M.O. McCarty always wanted Walter to come and stay with him. So here’s the old Klansman, and his favorite people were me and Walter.

Walter would say to me, “Bob, do I have to go stay at M.O.’s this weekend?” I’d say, “Yeah Walter, you know, M.O. likes for you to stay over there.” And so he says, “Well, it’s okay, but you know M.O. and his wife they go to sleep as soon as it gets dark and the daughter,” she’s about 18 or 19, “she wants to play Bob Dylan and she wants to dance.” This is the white daughter of an old Mississippi Klansman, and a very dark Walter Collins, and Walter says, “I don’t know what to do.” I said, “Well, just be cool man.”

And how did others react to this interracial organizing?

One day, a group from California who had been supporting us came, two people, man and a woman. They’d been giving us a lot of money for the organizing. They would come to New Orleans, and they would always want to go to Mississippi and see the project, see “the people.” So they came down and we drove up to Mississippi in their El Dorado Cadillac. And M.O. McCarty was the person who was supposed to be the host for that day. Whenever there were people from outside, the local union or the working people’s committee would appoint somebody to be the host. So M.O. was the host, and we went to the meeting at the community house that Sunday morning, and then in the afternoon there was a big rally in the next county. We had 1,500, 2,000 workers, half Black, half white, half with Wallace stickers and half with NAACP stickers, in the cow pasture meeting together. This is in 1968, 1969, in Mississippi.

On the way out there, this woman from California says, “Well tell me, Mr. McCarty,” referring to my white Mississippi friend, “what do you think of the Negroes?” So, M.O. said, “Oh, I get along fine with them, some of my best friends are Black.” And then he said, “The only thing I don’t want is to have to eat with them or have one marry my daughter.” The typical line, right? So, that was a conversation stopper.

When we got to the rally, M.O. kind of wandered off, so the woman turned to me and she said, “How can you work with people like that?” And I said, “Well, that’s the people we supposed to be working with! What do you think?” She asked me, “Well, didn’t you hear what he said?” And I said, “Of course I heard what he said, but I think you’re missing the point.” She said, “What do you mean?”

So M.O. was over talking to some of his old Klan buddies and I waved to him, I said, “M.O.! Come here!” So he comes back over and I said, “M.O., where did you have dinner today?” He said, “Over at the community house.” I said, “M.O., did you stand up when you ate dinner?” He said “No, I sat at the table with everybody else.” I said, “Do you remember who was sitting there?” He said, “Well, Ivory Gary was on my right and James Nealy was on my left.” And I said, “What color is Mr. Gary?” He said, “He’s Black.” I said, “What about James Nealy?” He said, “He’s Black.” And I said, “M.O. if you don’t have better luck with your daughter than you’re having with your eating, you’re going to be in really big trouble.” So M.O. slapped his knee and he said, “I see what you talking about!” And I already knew that his daughter was wanting to dance to Bob Dylan records with Walter Collins.

So, you see, we knew that people’s rhetoric can be the last thing that’ll change. We told them we don’t care what you believe as long as you act in an equal way, knowing that people don’t want a disconnect between what they’re doing and what they’re thinking, and their thinking begins to change. But that’s just one story. That’s our poor people’s organizing.

Looking at the example of that transformation, what lessons do you think we can draw from that experience for our work in building a New Poor People’s Campaign for today?

One of things I want to tell you as young organizers, the last thing that liberals or progressives or political militants who are white want to do is talk to people who are actually white racists. That’s the last thing they want to do. To be in their homes, to be in their weddings, in their funerals, and in their churches, you know.

But when we do SNCC-type organizing we become part of the community. This is the kind of organizing that goes on. I mean this is up close and personal. This is engaged. These were people that worked in the plant together for 20 years now.

You know, Laurel, Mississippi, is where the killers of the three Civil Rights workers in 1964 were from. That was masterminded right out of Laurel. So when we were organizing in Laurel we were organizing in the mouth of the Klan, and we went directly at the Klan members and we organized them away from the Klan. So, it could still be done today.

This interview was originally posted on the Kairos Center website and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission. Kairos works to strengthen and expand transformative movements for social change that can draw on the power of religions and human rights.