In the battle to combat obesity and its associated health risks, there’s a new sheriff in town: the sugar tax. In response to an ominous rise in rates of heart disease and diabetes, more than 43 cities have attempted to levy a tax on soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages. A soda in Berkeley, Calif., is now taxed at a penny per-ounce. In Mexico, the rate is as high as 10 percent.

Not everyone approves of this approach. The sugar tax has drawn criticism from public health officials and journalists alike. Some claim that it disproportionally targets low-income communities. Others say it just won’t work. Mark Bellemare, assistant professor of applied economics at the University of Minnesota, predicts the tax will result in a meager a 0−2.6 percent decrease in soda and sugary beverage consumption.

However, the debate over whether to tax or not to tax is nothing more than a distraction from the underlying problem. It might educate consumers or marginally influence buying habits, but it’s still just a band-aid, allowing Americans to heap blame on those who “chose poorly” without challenging deeper systems of inequality that afflict marginalized communities. It’s true — consumer choice heavily influences obesity rates. But for low-income and minority communities, who make up a large portion of America’s obese, the problem isn’t an unwillingness to make good choices, but the absence of choice in any form.

Nationwide, both environment and income level are strongly correlated with the ability to engage in healthy behaviors — and therefore, with obesity. A recent study from the Food Research and Action Center emphasizes this relationship, implicating the dearth of grocery stores, the lack of time and resources to exercise, and the junk food marketing campaigns that directly target low-income communities as core components of the obesity epidemic.

Slapping a sugar tax on this problem ignores its inherent complexity, allowing officials to claim that they are doing their part without addressing the pressing underlying elements. When famed UK health advocate Jamie Oliver championed a sugar tax to Britain’s House of Commons Health Committee, he argued that the tax would be the “single most important change” that could be made in the fight against childhood obesity, neglecting to consider opportunities for more substantive reform. While similar initiatives occasionally address socioeconomic factors, their overwhelming focus on taxation nevertheless encourages the notion that a surface-level solution will suffice.

This simply isn’t true. Solving the obesity epidemic will require major structural changes, ranging from the integration of healthier options in low-income communities to stricter regulation of the corporations that produce such lethal products.

Yet this summer, Philadelphia became the newest subscriber to the sugar tax philosophy. On June 16, the City Council approved a 1.5 cent-per-ounce tax on sugary drinks and diet sodas. While proponents heralded the tax as a public health victory, the results of previous initiatives cast further doubt upon their optimism. Although Mexico’s soda tax initially lowered rates of soda consumption by 1.9 percent, the market has since experienced a turnaround. By some estimates, soda consumption has now exceeded pre-tax levels, putting consumers at an even higher risk for contracting obesity-related diseases than they were before the tax was implemented. It’s clear that in the absence of serious reform, the wound underneath will continue to bleed.

Fat in Philly

Philadelphia’s efforts to combat obesity first made headlines in 2001, after Men’s Health magazine had recently named Philadelphia the “fattest city in America” and then-mayor John Street decided to take action. Street set his city a lofty goal: lose 76 tons in 76 days. Teaming up with an army of doctors, public health experts and celebrity figures, he launched the “76 Tons of Fun” initiative, a plethora of city-wide health and fitness programs that ranged from free exercise classes to vegetarian cooking demonstrations. In total, Street recruited over 26,000 participants.

Unfortunately for Street, “76 Tons of Fun” didn’t make a dent. Street never disclosed the results of his initiative but, nine years later, a CDC study reported that 60.1 percent of Philadelphians were still overweight or obese.

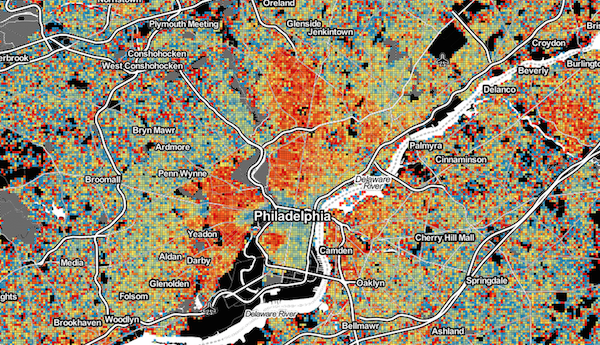

A map of obesity in Philadelphia where the CDC reports nearly 70 percent of children in North Philly are overweight or obese. (Image: RTI International / phillymag.com)

In 2010, Mayor Michael Nutter proposed a new plan: a 2 cent-per-ounce soda tax. This tax, he hoped, would disincentivize consumers from buying unhealthy drinks while simultaneously raising crucial revenue for city infrastructure.

Unsurprisingly, the American Beverage Association (ABA) responded with fury. Given that high-fructose corn syrup, one of the ABA’s most profitable — and most dangerous — sweetening agents, was to be included in the tax (along with myriad other corn-based sweeteners), Philadelphia’s proposal posed a threat to the industry’s profit margin. Between 2010 and 2016, the ABA spent over $5 million in Philadelphia advertising against the proposed tax, claiming that it would be ineffective in reducing the city’s long-term obesity rates.

When pro-tax advocates finally claimed victory this June, Nutter celebrated via Twitter, congratulating current mayor Jim Kenney on the victory. “It was the right thing for Phila when I proposed it 5+ years ago,” he wrote, “& it’s right today!”

Although motivated by profit, the ABA’s conclusion is correct. In Arkansas, where a sugar tax has been on the book for decades, obesity rates continue to rise at an alarming pace. Between 2011 and 2014, they jumped from 30.9 percent to 35.9 percent. In West Virginia, a state with similar legislation, they have grown from 32.4 percent to 35.7 percent. While this increase can’t directly implicate the sugar tax, one thing is clear: it isn’t the “magic bullet” solution its proponents promised.

Considering these statistics, how could so many elected officials get it wrong? Unfortunately, they’re working with a fundamentally flawed logic. When consumers lack both supermarkets with healthy alternatives and time to prepare their own food, and are the primary targets of junk-food marketing campaigns, incentivizing better choices won’t change much. To begin to curb obesity rates, legislation must target the context — the obesity inducing environments that catalyze these choices in the first place.

Choice vs. context

In a world where many still believe in the efficacy of choice-based public health campaigns, food justice advocate Julie Guthman is among the less devout. Guthman links our cultural obsession with “choice” with the rise of neoliberalism, which asserts that we are all independent actors in the marketplace, and that our health is a direct consequence of our choice. Environment? Irrelevant. Socioeconomic status? An excuse. In the neoliberal world, we all get a cake, we all get an apple, and it’s up to us to decide out of which to take a bite.

Following this logic, the soda tax makes sense. As long as we are incentivized to make better choices, nothing should stop us from slimming down. Right?

The data from Arkansas and West Virginia says otherwise. And despite the reign of consumer-choice ideology in recent years, America is getting fatter in almost every state. In 2011-2012, the CDC reported that 34.9 percent of adult Americans were obese. By 2014, that number had risen to 37.7 percent, and there’s no evidence that it will fall any time soon.

Graph showing prevalence of obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by sex and age in the United States from 2011 – 2014. (Image: CDC)

Guthman offers a different solution. In her 2006 book Weighing In, she notes:

The absence from public discussions of acknowledgement that our food system is part of a political economy that systematically produces inequality … instead promulgating the notion that education will change how people eat — and thus transform the food system.

The inequality Guthman cites is the key factor in the obesity epidemic. The largest consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages are poor and people of color. Out of all demographics, black women who earn less than 130 percent of the poverty line have the highest rates of obesity.

Despite what neoliberal advocates want us to believe, choices aren’t made in a socioeconomic vacuum. We know that poor people aren’t poor because they’re lazy. We understand the various structural forces that continue to marginalize the marginalized. Similarly, poor people aren’t fat simply because they make bad choices. It’s because choices are constrained by socioeconomic contexts.

Debating the efficacy of the soda tax fails to address the structural violence that draws low-income communities into this vicious cycle of processed food, obesity and poverty. Education doesn’t work if 2.3 million U.S. households without a vehicle live more than a mile from the nearest grocery store. These households don’t have access to the proverbial apple that neoliberalism suggests. If all that’s available is the cake, can we really blame people for eating it?

A new solution

If consumer-choice initiatives won’t work, what will? As Guthman suggests, comprehensive reform is crucial. If government and public health officials are to expect at-risk communities to make better choices, they must ensure that these choices are accessible.

Mobile food markets are a promising first step. Loaded to the brim with healthy products, these “supermarkets-on-wheels” provide communities with fresh fruits and vegetables they would otherwise be unable to access. Already, these trucks have significantly increased consumption of healthy foods in the communities in which they operate — proving that when consumers actually have access to healthy foods, they will make good choices (even without financial incentives).

Farmers team with a mobile market to supply fresh produce to residents of Camden/Philadelphia neighborhoods. (Photo: Greensgrow Farms / USDA)

On a more radical note, corporations must be held accountable. We would never allow Big Pharma to peddle diabetes-inducing pills to low-income communities, even if they pled innocent under the guise of consumer choice. So why do we permit it from the food industry? Brands such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi must claim responsibility for their dangerous drinks, and should be required to end targeted marketing campaigns and reduce the sugar levels in their sodas to a healthier level.

These types of reform will require effort, far more effort than simply handing down a sugar tax while shooting reproving glances at the poor. But obesity, and the socioeconomic issues to which it is inextricably linked, are complex as well. They won’t be solved by a tax, and they definitely won’t be solved by scapegoating those least capable of changing the contexts in which they live.

[If you like what you’ve read, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the bear on the upper right of your screen. Also, follow RAITT on Twitter @RuralAmericaITT]