Last weekend, amidst much talk in the media of the proposed Trump budget, my wife and I were crossing Coal Country on a car trip from Chicago to Washington DC, and we happened to stop for the night in the town of Somerset, Penn. Quickly, we learned that the area contained not only the crash site of Flight 97 (the famous “third plane” on Sept. 11, 2001) but also the Quecreek Rescue site where in July 2002, nine miners, trapped for more than three days in a collapsed and flooded underground pit, were saved by a heroic intervention combining the expertise of the federal Mine Safety Health Administration, area machine shops that fashioned an emergency drill and a National Guard helicopter.

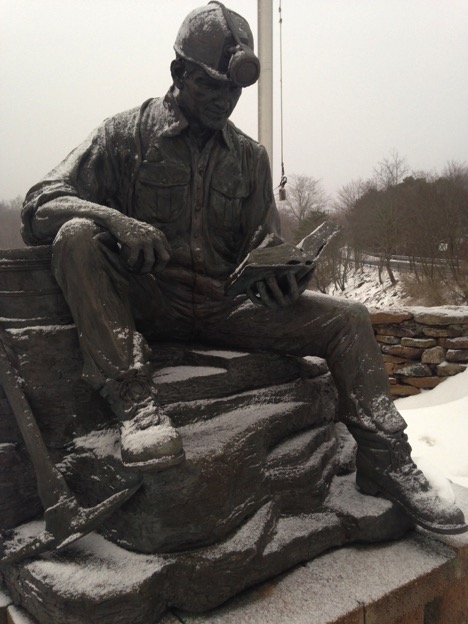

To mark these unrelated but closely-occurring events, local entrepreneurs have even established a “Tragedy and Triumph” bus tour across Somerset County. Whereas the National Park Service has erected an impressive memorial complex in honor of the Flight 97 victims, a simple but moving monument by Zanesville, Ohio sculptor Alan Cottrill — and funded by contributions from a variety of local citizens and businesses — commemorates the Quecreek rescue operation. The monument pictures a sitting miner, his pickaxe to the side, with a book in one hand and an apple in the other.

Given current circumstances, the Quecreek statue’s juxtaposition of worker subject with symbols of learning riveted our attention. Only the day before our trip, Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney justified severe cuts in workplace and environmental regulation as well as a zeroing out of the national arts and humanities agencies with a defining rhetorical question: “Could we as an administration, could I as a budget director look at a coal miner in West Virginia and say I want you to give money to the federal government so I can give it to the National Endowment for the Arts? We finally got to the point in the administration where we couldn’t do that.”

A larger image of Alan Cottrill’s statue of a coal miner. (Photo: Susan Levine)

Trump’s white working-class base, Mulvaney implied, had more pressing needs to contend with than any arts agency could possibly supply. The anti-arts initiative from the White House followed a public appeal from conservative columnist George F. Will to abolish an agency pushing liberal vagaries like “community and connectedness,” “diversity” and “self-esteem.”

Yet, before the current attempt to stir the class resentment of so-called white populists, it was not so clear that education and the arts functioned as mere proxies for liberal-professional elites. At Quecreek, Cottrill’s miner — perhaps reflecting the sculptor’s own trajectory as the first in his family to graduate from high school — gazes at the following lines (drawn from an amateur contemporary poet), etched in stone:

Those who work the mines/And they who read great books/Are but one, their name is human/By the labor of their hands/through the exercise of their minds/And in the strength of their spirit/They will prevail.

Such a spirit, moreover, is in keeping with deep working-class traditions combining class pride with a yearning for self-improvement as well as group empowerment. In the aftermath of the American Revolution, numerous artisan associations proclaimed, “By hammer and hand, all arts do stand.” A century later, American labor unions regularly fought for expanded public education and free public libraries. Through the 20th century they would establish scholarship programs for the children of union members and occasionally even pioneer their own arts programs, like Local 1199 hospital workers’ Bread and Roses project.

Nor do the public arts and humanities advocates in Coal Country resemble the caricature of touchy-feely snobs and/or ideological zealots that is pushed by would-be de-funders. Susan Landis, longtime chair of the West Virginia Commission on the Arts, sounds a populist note of her own in emphasizing that arts programs should “not just stay in the state capital.” “Especially in rural America, which in our state means coal-mining areas,” she says, “small amounts of money can make a huge difference.”

Funded West Virginia artists include bluegrass musicians, square dance callers and regional quilt-makers. The state arts’ commission, which as in most states receives half of its funding from the NEA, is particularly proud of two outreach projects for public school students. One is support for the national Poetry Out Loud competition that hones performance skills for children likely unexposed to private piano or dance lessons. The other is the state’s collaboration with the VH1 Save the Music Foundation: taking advantage of a program that started with the funding of inner-city school bands, the arts council has helped award 30 new instruments to at least one school in each of the state’s 55 counties.

Reaching far into the depressed coal fields of the state, such initiatives, Landis is convinced, “keep kids in school” while generally buttressing “community spirit.” “People like George Will,” she says, “miss the power of the arts to diversify our economy. When you see what young people are doing with design and technology and advertising, especially with [access to] broadband, that’s art!”

Like the apple in the hand of the Quecreek miner, Landis believes that knowledge will power a future beyond dependence on coal. “We need alternatives in West Virginia,” she says, “and the arts provide one avenue to find those things.” Whether we’re talking about miners trapped underground or young people facing limited economic opportunities, a region-wide “rescue” surely involves a smart and coordinated public-private partnership. But where is that in today’s political landscape?