How To Sell Off a City

Welcome to Rahm Emanuel’s Chicago, the privatized metropolis of the future.

Rick Perlstein

In June of 2013, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel made a new appointment to the city’s seven-member school board to replace billionaire heiress Penny Pritzker, who’d decamped to run President Barack Obama’s Department of Commerce. The appointee, Deborah H. Quazzo, is a founder of an investment firm called GSV Advisors, a business whose goal — her cofounder has been paraphrased by Reuters as saying — is to drum up venture capital for “an education revolution in which public schools outsource to private vendors such critical tasks as teaching math, educating disabled students, even writing report cards.”

GSV Advisors has a sister firm, GSV Capital, that holds ownership stakes in education technology companies like “Knewton,” which sells software that replaces the functions of flesh-and-blood teachers. Since joining the school board, Quazzo has invested her own money in companies that sell curricular materials to public schools in 11 states on a subscription basis.

In other words, a key decision-maker for Chicago’s public schools makes money when school boards decide to sell off the functions of public schools.

She’s not alone. For over a decade now, Chicago has been the epicenter of the fashionable trend of “privatization” — the transfer of the ownership or operation of resources that belong to all of us, like schools, roads and government services, to companies that use them to turn a profit. Chicago’s privatization mania began during Mayor Richard M. Daley’s administration, which ran from 1989 to 2011. Under his successor, Rahm Emanuel, the trend has continued apace. For Rahm’s investment banker buddies, the trend has been a boon. For citizens? Not so much.

They say that the first person in any political argument who stoops to invoking Nazi Germany automatically loses. But you can look it up: According to a 2006 article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, the English word “privatization” derives from a coinage, Reprivatisierung, formulated in the 1930s to describe the Third Reich’s policy of winning businessmen’s loyalty by handing over state property to them. In the American context, the idea also began on the Right (to be fair, entirely independent of the Nazis) — and promptly went nowhere for decades. In 1963, when Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater mused “I think we ought to sell the TVA” — referring to the Tennessee Valley Authority, the giant complex of New Deal dams that delivered electricity for the first time to vast swaths of the rural Southeast — it helped seal his campaign’s doom. Things only really took off after Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s sale of U.K. state assets like British Petroleum and Rolls Royce in the 1980s made the idea fashionable among elites — including a rightward tending Democratic Party.

As president, Bill Clinton greatly expanded a privatization program begun under the first President Bush’s Department of Housing and Urban Development. “Hope VI” aimed to replace public-housing high-rises with mixed-income houses, duplexes and row houses built and managed by private firms.

Chicago led the way. In 1999, Mayor Richard M. Daley, a Democrat, announced his intention to tear down the public-housing high-rises his father, Mayor Richard J. Daley, had built in the 1950s and 1960s. For this “Plan for Transformation,” Chicago received the largest Hope VI grant of any city in the nation. There was a ration of idealism and intellectual energy behind it: Blighted neighborhoods would be renewed and their “culture of poverty” would be broken, all vouchsafed by the honorable desire of public-spirited entrepreneurs to make a profit. That is the promise of privatization in a nutshell: that the profit motive can serve not just those making the profits, but society as a whole, by bypassing inefficient government bureaucracies that thrive whether they deliver services effectively or not, and empower grubby, corrupt politicians and their pals to dip their hands in the pie of guaranteed government money.

As one of the movement’s fans explained in 1997, his experience with nascent attempts to pay private real estate developers to replace public housing was an “example of smart policy.”

“The developers were thinking in market terms and operating under the rules of the marketplace,” he said. “But at the same time, we had government supporting and subsidizing those efforts.”

The fan was Barack Obama, then a young state senator. Four years later, he cosponsored a bipartisan bill to increase subsidies for private developers and financiers to build or revamp low-income housing.

However, the rush to outsource responsibility for housing the poor became a textbook example of one peril of privatization: Companies frequently get paid whether they deliver the goods or not (one of the reasons investors like privatization deals). For example, in 2004, city inspectors found more than 1,800 code violations at Lawndale Restoration, the largest privately owned, publicly subsidized apartment project in Chicago. Guaranteed a steady revenue stream whether they did right by the tenants or not — from 1997 to 2003, the project generated $4.4 million in management fees and $14.6 million in salaries and wages — the developers were apparently satisfied to just let the place rot.

Meanwhile, the $1.6 billion Plan for Transformation drags on, six years past deadline and still 2,500 units from completion, while thousands of families languish on the Chicago Housing Authority’s waitlist. Be that as it may, the Chicago experience looks like a laboratory for a new White House pilot initiative, the Rental Assistance Demonstration Program (RAD), which is set to turn over some 60,000 units to private management next year. Lack of success never seems to be an impediment where privatization is concerned.

Chicago Inc.

Privatization plainly made sense to another witness to the Plan for Transformation: Rahm Emanuel, who served as a Chicago Housing Authority vice chairman from 1999 to 2001. After his time as a top aide in the Clinton White House, he made more than $18 million in two-and-a-half years as an investment banker, brought into the business by the man who just became Illinois’ new Republican governor, billionaire venture capitalist Bruce Rauner.

And as mayor, Emanuel has proven himself practically an addict when it comes to brokering deals with his former investment banker comrades and the other business interests he keeps on speed dial. As the Chicago Reader’s Ben Joravsky and Mick Dumke discovered when they filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the mayor’s private schedule, Emanuel almost never met with community leaders during his first year in office, but he met constantly with rich bankers like Rauner, BMO CEO William Downe and Larry Fink, chairman and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s biggest money management firm. These are his people.

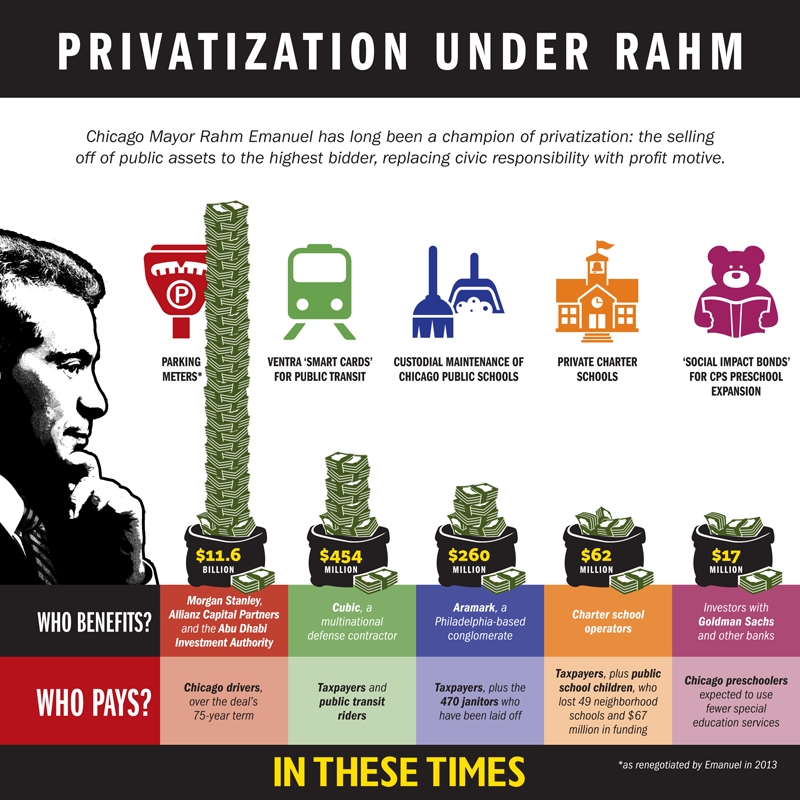

When he took office as mayor, Emanuel inherited several major deals with corporations for city services. One is infamous: the parking meter deal between Morgan Stanley, Allianz Capital Partners and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority — the poster child for privatization deals gone wrong.

Mayor Daley’s 2008 deal to sell off Chicago’s parking meter franchise was negotiated in secret; City Council members got just two days to study the contract before signing off on it. Under the deal, rates promptly skyrocketed. And worse: Not only does the privately owned Chicago Parking Meters get the money whenever one of Chicago’s fine upstanding citizens pumps money into a meter; CPM gets paid even when they don’t. Each parking meter has been assigned a “fair market valuation.” When the city takes what is called a “reserved powers adverse action” — anything from removing a meter that impedes traffic flow to shutting down a street for a block party — CPM can demand a payment for the loss of that meter’s “fair” market value for the entire time it’s down.

What’s more, a 2009 estimate from the city Inspector General found that the city had sold the meters for about half of what they were worth. Then, in 2010, Forbes estimated that the city had in fact been underpaid by a factor of 10.

What, then, did the new mayor do? “He simultaneously badmouths the deal and defends it to the death,” explains public interest lawyer Thomas Geoghegan, who argued in an unsuccessful lawsuit that the contract was invalid because it unconstitutionally usurped the police powers of the city. On the one hand, Emanuel loudly boasted he’d renegotiated the deal to the public’s benefit. Parking became free on Sunday (but the hours people had to pay to park on weeknights were extended, vouchsafing CPM’s profits). Meanwhile, he was careful to say nothing bad about the multinational consortium, which continues to bilk his constituents. That would discourage other would-be concessionaires — like the ones with whom he negotiated a $154 million deal to operate digital billboards along Chicago’s expressways for a term of 20 years.

That’s in keeping with the cash-up-front, consequences-later logic of privatization deals. An extreme example is a 2004 deal that then-mayor Daley won’t even be alive to see the outcome of: the leasing of the Chicago Skyway for $1.8 billion to a consortium composed of Macquarie, a Sydney-based investment firm, and Cintra, a Spanish private infrastructure developer, for 99 years.

In 2007, Chicago’s chief financial officer, Dana Levenson, explained the rationale for the deal to Businessweek: “There is money to be had, and cities need money.” He pointed out that because of the $1.8 billion cash influx, Chicago was able to pay off its debt, commit $100 million to social programs like Meals on Wheels, and have enough left over to earn as much interest income as it used to make from tolls (which now went instead to the concessionaires in Sydney and Spain). Sounds nice — unless you happen to drive on the Skyway. On January 1, the price to drive its eight miles rose to $4.50, up from the two bucks it cost when the city ran it, making it the highest toll-per-mile roadway in the United States; if prices had reflected only inflation, it would cost $2.50. To investors, that’s the point. As Timothy J. Carson, vice-chair of the Pennsylvania Turnpike commission, noted years ago in fighting a deal to privatize that highway: “There’s no magic here. These [deals] are largely driven by one factor: the permitted toll increases.”

As for the Skyway, the hit is likely to get worse — and the claimed benefits will fade, too. Research by John B. Gilmour of William and Mary University indicates that the longer road privatization deals last, the more they reward investors but shortchange the public.

He ran a mathematical model based on the deal the state of Indiana inked in 2006 to lease the Indiana Toll Road, the “Main Street of the Midwest,” for a 75-year term. The delightful initial cash payout closed the state’s budget deficit, But, according to Gilmour’s midrange estimate, by the time that deal reaches the last third of its term, only 13 percent of revenue goes to the public.

Why would politicians negotiate 75-and 99-year contracts that systematically shortchange their constituencies the longer they last? Because the concessionaires are able to exploit the simple fact that no politician, even ones named “Daley,” last in office that long. Politicians reap immediate glory for closing deficits without raising taxes and funding popular programs, an irresistible temptation. Voters blame the corporations that operate the roads for the toll increases and revenue shortfalls, not the politicians who wrote or voted for the deals in the first place. Then, when the damage is done, IBDYBD — “I’ll be dead, you’ll be dead,” to repurpose the phrase that became popular among the cynical Masters of the Universe who structured the financial time-bombs like mortgage-backed securities that tanked the global economy in 2008. A short-term infusion of cash that forces the recipient more and more into hock the longer the arrangement lasts: “It’s like going to the payday loan store,” explains Tom Tresser, a Chicago-based anti-privatization activist.

What Rahm hath wrought

Other cities and states did their homework and rejected the privatization fad. In 2008, Pennsylvania turned back Democratic governor Ed Rendell’s dream of selling off the state’s famous turnpike for 75 years to a consortium of Citi Infrastructure Investors and the Spanish company Albertis Infraestructuras. The proposed deal would have raised tolls by about two-thirds within 10 years (to $36.40 to travel from one side of the state to the other), would have eventually made the state pay the consortium for lost traffic during emergency road-closures, and would have turned over transportation-planning decisions to far-off corporate bureaucrats. And after Atlanta leased its water system to United Water Inc. in 1997, leading to a series of water-main breaks and billing disputes, the city’s watershed commissioner said, “I don’t believe the city will ever look at privatizing essential services again.”

Rahm Emanuel’s Chicago, though, presses ahead.

Soon after taking office, Emanuel announced the Chicago Transit Authority’s new Ventra “smart card” payment system for public transportation. Cubic, the San Diego-based defense contractor that got $454 million in taxpayer money to create it, had faced endemic complaints in nearly every other city in which it had been introduced. The system proved just as disastrous in Chicago: For months, card failures forced bus drivers to simply wave passengers through. Or customers were charged twice if their purses or backpacks brushed too close to the reader upon exiting a bus. Federal government employees found they could ride free by swiping their work IDs. The systematic glitches are devastating to the argument that business is better than government at delivering services.

Another wonky feature of the Ventra system is that it was designed to suck up the hard-earned money of millions of less-fortunate Chicagoans into bank coffers. The transit cards can double as debit cards, you see, promoted as a boon for Chicago’s un- and under-banked. But dig the customer fees hidden in the 1,000-page contract the city signed with Cubic: $1.50 every time customers withdraw cash from an ATM, $2.95 every time they add money to their online debit account with a personal credit card, $2 for every call with a service representative and an “account research fee” of $10 an hour for further inquiries, $2 for a paper copy of their account information, and, if you decide you’ve had enough, a $6 “balance refund fee.” This all makes mincemeat of the pro-privatization argument that “the marketplace” is more transparent than a government bureaucracy. The city might have been able to anticipate this before inking the deal had they paid attention to the fact that Money Network, the payment processing company partnering with Cubic, had received the lowest possible grade from the Better Business Bureau, and that another partner, MetaBank, was fined $5.2 million by federal regulators for a scheme to issue debit cards funded by tax refund loans at interest rates of up to 650 percent.

How did this all go down? Consider, as a clue, the case of one John Flynn. As the Chicago Tribune reported, Flynn was the Chicago Transit Authority’s vice president of technology from 2000 to 2008, then decamped for the private sector. During a four-year term at the Chicago division of Cubic, Flynn helped broker the $454 million Ventra deal. Then, last year, under Emanuel, he returned to the city’s employ.

Propagandists vaunt privatization as a brave new world beyond the icky quid pro quos of old-school municipal politics. Tell that to Deborah Quazzo — who might just laugh all the way to the bank. A year ago, when I first started researching this article, I sent Quazzo an email posing two simple questions: Given the work her firm does in education, did she anticipate recusing herself from school board decisions that presented a conflict of interest? And did she anticipate putting investments in a blind trust during her tenure? I never heard back. Then, this past December, the Chicago Sun-Times reported that companies in which she invested have reaped $2.9 million in business from Chicago Public Schools — compared to only $930,000 in the three-and-a-half years prior to her appointment.

She told the paper she saw no conflict of interest: “It’s my belief I need to invest in companies and philanthropic organizations who improve outcomes for children” — and that she wasn’t involved in the deals or aware that her companies’ take had tripled since she took office. Which would make her either a pretty inattentive school board member or a pretty inattentive executive: Some of her companies that had preexisting contracts with CPS cut their prices after Quazzo joined the school board so their bills would fall under the threshold that would require review by district bureaucrats. One of those bills came to precisely $24,999. The threshold for review? $25,000, naturally. Privatization is building a new Chicago machine in many respects more offensive than the machine of old.

The $14 billion Philadelphia-based facilities service conglomerate Aramark has a well-earned reputation for unsavory labor relations and shoddy business practices — for instance, the maggots discovered in food served in Aramark-run prison cafeterias in Michigan and Ohio. That didn’t keep the Chicago School Board from voting in March of 2014 to give Aramark a $260 million, three-year contract to handle custodial maintenance. Before the first month of the 2014 school year was out, however, a group of Chicago principals released a report describing filthy conditions in their schools since Aramark took over, including rodents, insects, mouse droppings and urine left in toilets for weeks. Conditions had been so bad just before the schools opened that parent and teacher volunteers had pitched in with cleaning.

What happened next? Within days of the report’s release, Aramark announced it was laying off 470 of its janitors, reducing the custodial labor force by almost 20 percent. In response to complaints that such layoffs help destroy the working class, Chicago Public Schools CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett, an Emanuel appointee, all but boasted about one of the most problematic aspects of privatization: the way it allows public officials to evade accountability. The Chicago Sun-Times paraphrased her: “They are employed by private companies, so it’s not the district laying them off.”

Of course, another thing that elites like about privatization is that it lets them lay off public employees — especially unionized ones. In Chicago, privately run charter schools that replace traditional public schools are not covered by Chicago Teachers Union contracts, and most are not unionized. Before the Chicago Skyway was privatized, the toll-takers were full-time city employees with full benefits. Now many are part-time contractors without benefits. When a Japanese-owned technology company took over responsibility for the call center that handles water bill complaints, jobs were outsourced to part-timers. All told, since 2009, the city has cut 5,000 jobs, in addition to laying off 1,700 public-school employees. This is bad not just for the workers who lost their jobs and the labor movement generally, but could serve to drive down wages for all workers in the city.

Privatizers like Emanuel say they have no choice: The city is going broke. That alibi is threadbare. Shortly after his inauguration, Mayor Emanuel threatened 625 layoffs unless the city’s unions acceded to a set of work rule changes. In response, the city’s Coalition of Unionized Public Employees — which represents 6,400 workers — quickly released a study proposing to save the city $242 million. The plan: Adopt more efficient scheduling and contracting procedures, get rid of unneeded middle managers instead of front-line union workers — and, defying conventional wisdom, replace private contractors with city workers. According to two COUPE principals, Chicago Federation of Labor President Jorge Ramirez and Laborers Local 1001 business manager Lou Philips, they never got a direct response from City Hall. “We’re saying we can save you more than $200 million and they don’t even read it!” Ramirez told Emanuel biographer Kari Lydersen.

So things rest: Most privatization deals fail every public policy test. There’s little record of successful competition between concessionaires to deliver services more efficiently. The very logic is faulty, because most government services are what economists call a “natural monopoly” — which turns out to be what makes it so attractive to capitalists in the first place: “Infrastructure is ultra-low-risk because competition is limited by a host of forces that make it difficult to build, say, a rival toll road,” as Businessweek explained way back in 2007. “With captive customers, the cash flows are virtually guaranteed.” Meanwhile, transparency is plainly a joke; indeed, aldermen in hock to Mayor Emanuel have let languish an ordinance drafted by unions and progressive alderman demanding actual transparency. So, what’s really going on here?

It’s about money and power.

Consider, finally, the mystery of Emanuel’s “infrastructure trust.” The idea was announced with great fanfare in March 2012 as an innovative way to pour private money into public goods like airport expansion, street and water improvements, and an expanded commuter rail network. An “integrated, comprehensive approach” for “building a new Chicago,” Emanuel called it — with little risk to the public. The PowerPoint presentation alderman watched before voting 41 to 7 to approve the deal contained only five slides. The New York Times credulously reported the city’s estimate that the trust would create “30,000 jobs over the next three years.” How? Three years in, with not a single new job created, no one seems to have any idea.

Maybe they’re just working out the kinks. Chicago Public Schools certainly hasn’t given up on the idea. In late 2014, the school board and the City Council approved a $17 million agreement with several investment banks, including Goldman Sachs, to expand preschool using “social impact bonds.” The plan hinges on “success payments” that are triggered if children perform well on kindergarten readiness tests and third-grade literacy tests. The better kids do, the more investors get — up to double their money over the 16-year program, according to an analysis by the education magazine Catalyst Chicago. The deal, Catalyst explains, “relies on a complicated formula that poses little risk to investors … largely due to the proven track record of the project’s chosen preschool program.” Benefit to the public hardly seems the primary aim when you consider the expectation — built into the deal — that Chicago children will be using fewer special education services.

Chicago’s NBC affiliate, WMAQ, editorialized, “Once again, the city is about to enter into a complex, long-term financial transaction with millions of dollars at stake with almost no debate, little understanding of how the program works, and no third party to weigh in on the potential risk and rewards” — with children as collateral, to boot. Why? Follow the money. Rues Tom Tresser: “These are investment bankers at work cooking up business for their campaign contributors. … The banks and billionaires who are sitting on piles of cash are looking for some sweet deals, like Morgan Stanley’s getting $10 for every $1 they invested in our parking meters. They play. You pay.”

What’s next? Now that Emanuel is gliding to likely re-election in February, quite possibly a municipal constitutional apocalypse. The enabling legislation for his infrastructure trust includes the following language: “To the extent that any ordinance, resolution or order of the city is in conflict with the provisions of this ordinance, the provisions of this ordinance shall be controlling.” It sounds like a formula to turn the governing of the City by the Lake over to the bankers on a street called Wall. When Chicago voters go to the polls on February 24 to decide whether to keep Rahm Emanuel as their mayor or replace him with someone else, this is what that race should be all about.

Rick Perlstein, an In These Times board member, is the author of Reaganland: America’s Right Turn, 1976-1980 (2020), The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan (2014), Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (2008), a New York Times bestseller picked as one of the best nonfiction books of the year by over a dozen publications, and Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus, winner of the 2001 Los Angeles Times Book Award for history. Currently, he is working on a book to be subtitled How America Got This Way.