For centuries, hunters have relied on lead ammunition to quickly and humanely kill game, but with each shot they release a potentially lethal poison into the environment, threatening vulnerable animal populations.

While harmless to humans, the gut piles and carcasses hunters regularly leave behind often contain lead fragments, which can be deadly for scavengers who eat them, particularly raptors like bald and golden eagles, California condors and turkey vultures.

Consequently, a seemingly unlikely alliance between sportspeople and environmental activists has formed to tackle the issue by advocating for copper and other non-lead options and promoting hunters as environmental stewards.

Hunter Russell Kuhlman, who serves as the Institute for Wildlife Studies’ non-lead ammunition outreach coordinator for California, says, “I think there’s a movement within the hunting community towards people wanting to get into the conservation and support of wildlife by hunting. [It’s] not so much the good old boys’ club of hanging out with your friends and shooting the biggest deer that you see.”

In a time when species extinction rates are 1,000 times higher than if humans didn’t exist, the recovery of bald eagle populations has been viewed as a successful conservation effort. But the majority of injured and sick eagles and birds brought into wildlife rehabilitation facilities around the country test positive for lead.

Although no federal agency keeps comprehensive track of wildlife lead poisoning, a documented 130 species, which include mammals, reptiles and amphibians, have been exposed or killed by ingesting the poisonous heavy metal.

Kuhlman says bald eagles’ patriotic symbolism has brought attention to the issue — including a recent high-profile eagle death in the nation’s capital — but that only in recent years has published research focused on lead ammunitions’ environmental consequences. He says, in the past, many avian populations were too small to conduct comprehensive studies.

While lead remains the industry standard because it’s accurate and affordable, the bullets are prone to shattering on impact. When fragments are ingested, they can not only be lethal, but also in lower doses, attack an animal’s brain and nervous system.

Impaired flight from lead leaves birds susceptible to injury or death by obstructions like cars and power lines. Due to direct and indirect mortality, it’s difficult to track lead deaths, especially because poisoned birds often hide while dying and can be scavenged by larger animals. Consequently, Kuhlman and others across the United States are raising awareness with environmental organizations, hunting associations and other invested parties.

Leland Brown, the non-lead hunting education coordinator with the Oregon Zoo, talks to sportspeople around the state, which is known for big game deer, elk and cougar hunting.

“We’re trying to get some of the larger national groups engaged in this issue and understanding that this is about how as hunters we can continue to make sure we aren’t having any unintended consequences,” says Brown. “It’s supposed to be a one shot, one kill. With a non-lead bullet, I can guarantee that.”

Why hunters need to be at the forefront of the non-lead effort

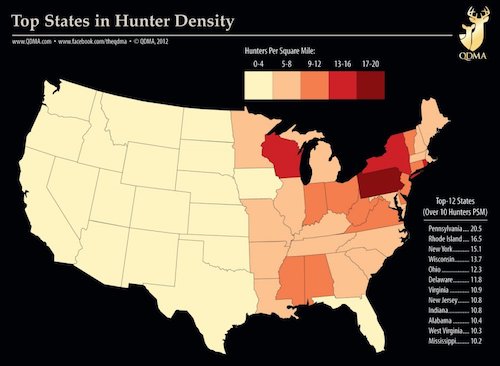

Although the majority of American hunters live in the East and Midwest, much of the non-lead movement is based in the western United States, where many of the most impacted populations live. The Klamath Basin in southern Oregon and northern California is home to the largest wintering concentration of bald eagles in the lower 48. California condors, an endangered species, are also susceptible to lead poisoning, particularly in their namesake state and Arizona.

In 2013, largely because of the damage to condors, California took the seemingly progressive charge of being the first state to ban lead bullets — a ruling which is slowly going into affect, with complete prohibition to be implemented by July 2019. Although this seems like a move non-lead advocates would applaud, Kuhlman and Brown believe outlawing lead bullets is a step in the wrong direction.

They explain that ammunition bans are difficult to carry out because much hunting occurs on private land, and it’s next to impossible for a state enforcer to know what kind of ammo is loaded in a firearm. On a larger scale, Kuhlman says, restrictions often pit hunters against environmentalists, without giving either party a fair say in crafting legislation.

As one of the Obama Administration’s final acts, one day before Trump’s inauguration, outgoing U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Director Dan Ashe issued a ban on lead bullet use on federal lands. But this proved short-lived. Almost immediately after Ryan Zinke, Trump’s pick for Interior secretary, was sworn in last March, he overturned the ban stating that “affected stakeholders,” i.e. hunters, had not been considered.

“I think the best way to do that would be to involve states and hunting organizations and even bring in groups like the National Audubon Society and have them all sit down at a table together and discuss how to best implement that,” says Kuhlman. “And in Dan Ashe’s order there was none of that. It was kind of black and white.”

In some cases, nationwide bans have proven effective: A 1991 prohibition of lead shot used for waterfowl hunting helped prevent “species threatening” die-offs of aquatic game birds. Many states have also outlawed or restricted lead fishing sinkers, jigs and other tackle, which have poisoned loons and other marine life, but lead use still abounds in upland hunting.

Gordon Batcheller, a retired former chief wildlife biologist for the New York Department of Environmental Conservation who is active in the non-lead movement, says it’s important that government agencies “respond in a regulatory way when documented environmental problems are causing population level impacts.”

While it’s easy to view lead bullets as a partisan issue — especially with groups like the National Rifle Association (NRA) presenting it as an attack on gun rights—Kuhlman, Brown and Batcheller agree that it’s crucial for hunters to be at the forefront. On a larger scale, through non-lead advocacy, they see hunting returning to its roots as a way to gather sustainable, safe food sources and to connect with nature.

And they have a large audience: Kuhlman and Brown individually give presentations to thousands of hunters every year. Batcheller also organizes workshops in New York and around the country. In addition to sharing research on the benefits of switching away from lead, they bring copper ammo and give hunters the opportunity to try alternatives.

“When you give someone the information, the majority of the time, they’re smart enough to make the correct decision,” says Kuhlman. “When you tell somebody that they have to do something and don’t give them any information on the reasoning, they tend to be a little more hostile towards that ban, law or rule.”

Brown, who previously worked for the Institute for Wildlife Studies in California, says he was a “punching bag” for hunters frustrated about the state ban. In Oregon, where some hunters fear similar legislation will eventually go into place, Brown sees more impact in encouraging hunters to make a voluntary switch.

A grassroots approach

Last summer, while working at a newspaper in the rural town of Klamath Falls, Ore., I attended Brown’s talk at a local hunting association meeting. As an August lightening storm brewed outside, Brown and members of a wildlife rehabilitation center were met with open minds. While some hunters expressed concerns about their pastime becoming a “rich man’s game” because of non-lead ammunition’s higher price, they invited Brown back for an ammo demonstration.

While this grassroots approach will take time, the leaders of the non-lead movement have faith they can shift hunting practices that go back generations.

“We’re dealing with a long-term issue that’s going to take a long-term solution,” Brown told me after the presentation. “We’re going up against at least 100 years of tradition, so people need an opportunity to wrap their heads around it and come to the other side.”