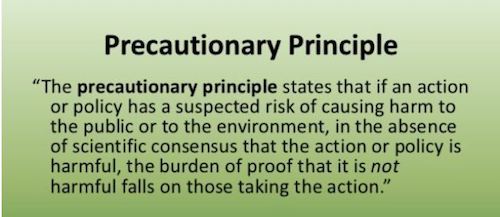

Questions of “sound science” and “burden of proof” invariably arise from conflicting indictments and defenses of industrial agricultural as either a threat or service to public interests. Defenders invariably insist that any regulation of industrial agriculture should be based on sound science, which places the burden of proof on the public rather than the perpetrator. In the absence of a scientific consensus, the precautionary principle would place the burden of proof on industrial agriculture rather than the public. Not surprisingly, the agricultural agenda of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the architect of industrial agricultural policy, lists its support of “science-based decisions” and opposition to the “precautionary principle” among its public policy priorities.

In a recent column, agricultural journalist Alan Guebert wrote: “For more than 20 years, farm and ranch groups, Congress, and Big Agbiz have used the phrase ‘sound science’ like a sharp shovel to undermine agricultural policy they want to alter or bury. Ask them to define ‘sound science,’ however, and you’ll get no clear explanation. That’s because ‘sound science’ is a political weapon, not a branch of knowledge.”

Another recent column by Washington Post health columnist, Christie Aschwanden, points out, “The sound science tactic exploits a fundamental feature of the scientific process: Science does not produce absolute certainty. Science is a process rather than an answer.” It is not scientifically correct to claim that a given scientific study or collection of studies actually prove anything. Science can only increase or decrease the confidence of scientists regarding the validity of fallacy of something — not provide absolute proof. Still, the defenders of industrial agriculture do not accept even a “scientific consensus” as “sound science.”

The term “sound science” was actually coined by the tobacco industry in the early 1990s, when it was defending itself against a growing body of evidence indicting tobacco smoking as a threat to public health. A 2001 Journal of Public Health article stated: “Public health professionals need to be aware that the ‘sound science’ movement is not an indigenous effort from within the profession to improve the quality of scientific discourse, but reflects sophisticated public relations campaigns controlled by industry executives and lawyers whose aim is to manipulate the standards of scientific proof to serve the corporate interests of their clients.”

Industrial agriculture today is a situation similar to that of the tobacco industry during the early 1990s. For example, a 2013 U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention report stated: “Scientists around the world have provided strong evidence that antibiotic use in food-producing animals can harm public health. Resistant bacteria can be transmitted from food-producing animals to humans through the food supply.”

A 2016 global summit of Heads of State at the United National General Assembly, concluded: “The high levels of AMR [antimicrobial resistance] already seen in the world today are the result of overuse and misuse of antibiotics and other antimicrobials in humans, animals, and crops, as well as the spread of residues of these medicines in soil, crops and water.” The statement continues, “Antimicrobial resistance is a problem not just in our hospitals, but on our farms and in our food, too. Agriculture must shoulder its share of responsibility.”

Similar scientific consensuses exist for several other public health risks posed by industrial animal agriculture or Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs).

The only defense put forth by CAFO proponents is that there is no “scientific proof” that any specific CAFO represents a specific public health risk. This is the same basic defense used by the tobacco company scientists who called attention to the many people who breathe secondhand smoke, or smoke themselves, and never suffer from lung cancer or heart disease. Risk does not imply certainty. Most people who drive aren’t injured in traffic accidents, but the government imposes and enforces traffic regulations to protect public safety. The consensus of public health scientists regarding the public health risks of CAFOs is clear, but there can be no proof of the unprovable.

Consequently, “burden of proof” should not be interpreted as requiring absolute proof or certainty but rather requiring a “scientific consensus.” Furthermore, scientific consensus does not require an absence of dissent or disagreement, but instead a predominance or prevalence of scientific opinion.

The precautionary principle holds that in cases of legitimate disagreement, the “burden of proof” that any resulting harm “would not” be severe or irreversible falls upon those who are proposing the policy or action, not on those who might be harmed. The precautionary principle is widely used in the practice of medicine, but defenders of industrial agriculture argue that is should not be applied in cases of public health risks associated with industrial agriculture. I believe they are wrong and eventually will be challenged successfully in court.

Regardless, there are circumstances where the precautionary principle clearly should be applied. In those cases where activities that pose potential public health risks are currently exempted from government regulation, the burden of proof clearly should fall on the beneficiary of the exemption — not on the public. The grant of special privilege entails special responsibility. A priority responsibility of any government is to protect public health and safety. It simply does not make sense that any government body or agency would exempt an activity from public health regulations without requiring a scientific consensus that such activities “do not” represent a significant risk to public health.

In defiance of common sense, CAFOs currently are exempted from virtually all public health regulations that apply to other industries producing comparable quantities and concentrations of toxic chemicals and biological wastes. Local governments are prohibited from regulating agriculture as they regulate other local industries. Recent “right to farm” laws give corporate agriculture the legal right to pollute and plunder rural America pretty much as they please. The few existing regulations of CAFOs are enforced only in response to complaints linked to specific violations.

In the absence of a scientific consensus that CAFOs “do not” pose significant public health risks, the biological and chemical pollutants associated with industrial animal production should be regulated the same as the biological and chemical pollutants associated with manufacturing or municipal waste disposal. The burden of proof clearly should be on proponents to prove that CAFOs “do not” represent a significant public health risk rather than on the public to prove they do. Authentic “sound science” would require action — not provide an excuse for inaction.

(”Industrial Agriculture versus the Public Interest” was first published on JohnIkerd.com and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission. To subscribe to John’s blog, or to learn more about his books and speaking engagements, click here.)