Rigging Democracy

Why the people won’t pick the next president or Congress--unless we act now.

Rob Richie

Many center-left political analysts tout Barack Obama’s re-election as affirmation that the unfolding demographic changes in the United States will inevitably vanquish the Republican Party as we know it. But before progressives sit back on their heels and wait for history’s just rewards, a deeper look at the 2012 election results is in order.

Obama’s victory overshadowed the fact that Republicans maintain control of the House of Representatives and won dramatic victories at the state level that seem almost mathematically miraculous in how they flout majority rule. Most strikingly, Republican congressional candidates were able to convert their national 49 percent of the major-party House vote into 54 percent of seats. (Democrats received 51 percent of the major-party House vote and 46 percent of seats.)

Republicans also increased the number of states over which they have monopoly control, securing the governorship and both legislative bodies of 26 states. This has national implications. The fact that Republicans have firm control over 13 Southern legislatures that make up more than one-quarter of states gives them veto power over any proposed constitutional amendment. Consequently, those seeking to overturn Citizens United by amending the constitution will need the support of at least one Republican-run legislature in the South.

Republicans also control government in most of the presidential battleground states, such as Florida and Ohio, which creates opportunities to exploit the vulnerabilities of our centuries-old voting rules. Democrats may have been thrilled that, despite the troubled economy, Obama won a landslide of electoral votes. But for Republicans such as party chair Reince Priebus, the apparent lesson is this: Rather than cater to an increasingly diverse and progressive America, they should rig the Electoral College in 2016. States have wide latitude to pass voting laws such as ID requirements, as well as the power to allocate Electoral College votes. That yields numerous opportunities for deck-stacking.

In addition to fending off vote-rigging efforts, Democrats must ultimately address a more fundamental flaw of the antiquated voting system — the one that gives Republicans their popular-vote-defying chokehold on the House of Representatives and many state legislatures. The GOP will continue to dominate the House, even when the Democrats win more votes, as long as we rely on a geographically defined, single-member district system to elect our legislators.

Electoral College cheat sheet

One of the U.S. Constitution’s quirks is that presidential elections are governed by the Electoral College, not the popular vote. Within this system, state legislatures have broad leeway to administer the presidential race, including the allocation of electoral votes and the mechanics of elections.

Both major parties have sad records of manipulating state election laws for partisan gain. While 48 states and the District of Columbia award all their electoral votes to the statewide popular vote winner, that wasn’t the norm initially. Many states either divided electoral votes or let state legislators appoint electors. Over the opposition of James Madison, the winner-take-all rule was adopted by most states by the time of Andrew Jackson’s presidency. Instructively, it was not driven by calculation of the public good, but by political leaders’ partisan desires to give as many votes as possible to their candidates.

The most glaring flaw of this approach is that candidates can lose the presidency despite earning the most votes. The popular vote was overturned by the Electoral College in four out of our 28 most competitive presidential races, including in 2000.

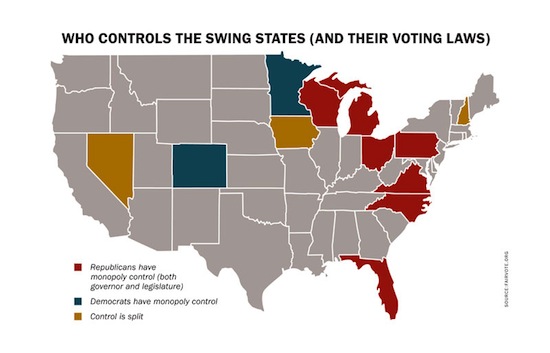

Republicans in key states are considering changes to the allocation of electoral votes that would virtually guarantee their party a presidential victory. Republicans are better-positioned than Democrats to try this approach: Of the 12 states that were considered “battlegrounds” in the 2012 campaigns — the ones deemed important enough to draw a major-party candidate for a general-election event — Republicans have monopoly control of seven: Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Wisconsin. Democrats control only Colorado and Minnesota.

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, Pennsylvania Senate Majority Leader Dominic Pileggi and Michigan elections committee chair Pete Lund are among the Republicans in key swing states backing or expressing interest in replacing winner-take-all rules with methods that would guarantee electoral votes to the Republican nominee.

First introduced by Bill Carrico, a Virginia Republican lawmaker, the most nefarious proposal is to award one electoral vote based on the presidential vote in each congressional district, and then give the state’s two remaining votes to the candidate who wins the most congressional districts. Here’s how vastly this would skew the popular vote: Had such a plan been enacted in 2012 in all seven swing states now under Republican control, Mitt Romney’s 126-vote defeat in the Electoral College would have been transformed into a 16-vote victory. To win under these circumstances, Obama would have needed to win a Romney stronghold such as Georgia or Arizona by increasing his national popular-vote margin to some 12 percentage points.

There are ominous signs that Republicans are willing to take this plunge into a whole new level of electoral-law manipulation. The National Journal’s Reid Wilson reported in December that, according to senior Republican officials, such proposals “are likely to come up in each state’s legislative session in 2013. Bills have been drafted, and legislators are talking to party bosses to craft strategy.” RNC Chair Priebus told the Milwaukee Journal on January 13 that “it’s something that a lot of states that have been consistently blue that are fully controlled red ought to be looking at.”

Alternately, Republicans may decide only to try to allocate electoral votes by district in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. That won’t ensure them the presidency, but would provide a big boost in close elections. Republican presidential candidates haven’t won any of these states since the 1980s, but Mitt Romney won 27 of their 40 congressional districts in 2012. Securing those 27 electoral votes (and six more under the Carrico plan) would shift more electoral votes to a Republicans than could be earned by sweeping the swing states of Colorado, Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada — and all without changing a single voter’s mind.

Legal vote fraud

Another insidious problem related to the Electoral College is the importance it places on a few swing states. Obama campaigned in only eight states in the final post-convention stretch of the 2012 race, every one of which was among the 15 battleground states of 2008. Absent reform, not a single new state is expected to be a 2016 battleground.

In short, the Electoral College rules have marginalized two-thirds of Americans in election after election — including a disproportionate share of racial minorities. The rules also invite partisan manipulation because of the growing ease in predicting where a small shift of votes could decide the White House. In 2000 and 2004, George W. Bush’s election hinged on a single state — Florida and Ohio, respectively. And in both states, Republican secretaries of state were widely criticized for changes to voting laws and election administration that may have tipped the outcome by suppressing the Democratic vote.

Grounded in that history, battles over voting laws raged in swing states in 2011 and 2012. Republicans in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Florida passed laws reducing early voting, requiring photo identification to vote and making it harder to register new voters. In testimony to Congress, Sen. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) called these laws “politically motivated and clearly designed to disenfranchise likely Democratic voters.”

Although the Department of Justice, civil rights groups and Democrats relied on Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act and other legal tactics to block implementation of many voting changes, most remain set to go into effect. Challenges will run their course in courts at the state level, and Congress is unlikely to intercede. As to the federal courts, the majority on the Supreme Court has already upheld voter identification requirements in Indiana, even without being presented with evidence of a single act of voter impersonation fraud.

And this year the Court is now expected to strike down or weaken Section 5 pre-clearance provisions, which empower the Department of Justice to block any laws diluting the voting rights of racial minorities in places with a history of discrimination at the polls. Without Section 5, several swing states, such as Florida, Virginia and North Carolina, will have wider latitude to pass legislation affecting suffrage.

Consequently, in 2016 we can anticipate more states implementing laws designed to limit voting rights of Democratic-leaning constituencies. And given the allure of the presidency potentially hanging by relatively few votes, we can also anticipate huge amounts of money freed by Citizens United to once again be dumped into swing states.

The winner-take-all problem

Republicans have a ready model for earning power with a minority of the vote: the House of Representatives. Despite winning the popular vote, Democratic candidates for Congress didn’t come close to winning a majority of House seats. To have earned even a one-seat majority in 2012, congressional Democrats would have needed another 7 million votes and an overall margin of some 8 percentage points. They’ll face the exact same distorted playing field in 2014, but with the added barrier of low turnout for midterm elections.

The culprit for this imbalance is a seemingly innocuous, even fair, one: single-member districts, in which each individual congressional district elects one individual representative. Many Americans assume that single-member districts are enshrined in our Constitution. That is not the case; they’re the product of federal statutes. Many states once elected House members statewide, but always by winner-take-all, in which 51 percent of votes could win 100 percent of seats. As the parties grew stronger, statewide elections made it easier for one party to sweep all seats. After more states began adopting statewide elections for clear partisan reasons, Congress in 1842 passed a law requiring single-member districts. That mandate has come and gone, most recently re-established in 1967 in the wake of the Voting Rights Act, when Congress acted to avoid Southern states adopting statewide elections to dilute the votes of newly empowered racial minorities.

But while often adopted for laudable purposes, single-member districts rarely provide voters with real choices and fair representation. Because of rigid voter preference, a majority of House seats are simply impregnable. Ninety-five percent of incumbents have won their races for re-election since 1994, with the average House race won by a 2-to-1 margin. Most seats are fixedly red or blue: In 2012, not a single Republican gained a seat in one of the 177 House districts where Barack Obama ran best in 2008 — and not a single Democrat gained a seat in one of the 177 districts where John McCain ran best. This increasingly partisan straitjacket on representation creates a problem for Democrats because Republicans have a strong partisan advantage in 241 districts and Democrats have an advantage in 194.

The Republican bias has existed for decades, and it has contributed to liberal Democrats never running for the House with the same boldness as shown by conservative Republicans. Any Democratic majority always depended on victories by more conservative Democrats who could win in right-leaning districts where their presidential standard-bearer would likely lose.

This reality has forced Democratic presidents and progressive Democrats in Congress to only craft policies that would appease their more conservative colleagues. With fewer votes splitting tickets as the identities become more distinct, “Blue Dog” Democrats have been decimated in Republican-leaning districts, dropping from 54 members in 2010 to just 15 today.

Republicans, on the other hand, can be more responsive to their base since their House majorities can depend entirely on candidates running in districts firmly aligned with their party.

Because of the increasing concentration of Democratic voters in cites, more than two-thirds of the 68 most overwhelmingly partisan districts are Democratic, with Republican voters more efficiently distributed in a system where geography matters. Tellingly, Mitt Romney was able to win 21 more congressional districts than Barack Obama — despite losing the popular vote by a 4-percent margin. With a majority of House seats held by Republicans in districts that went for Romney, it should be no surprise that the White House faces ongoing obstacles even after Obama’s convincing win.

Winner-take-all casts a pall over elections at all levels. Consider:

- The Senate, made up of 90 percent white-majority states, has only five people of color.

- Two out of every five state legislative races in 2012 were uncontested.

- At least 118 (out of 120) winners in North Carolina’s 2012 state house elections ran in districts that favored their party.

- Democrats in Georgia and South Carolina ran candidates in fewer than half of house seats in 2012.

Some believe that partisan control of redistricting is at the root of these problems. Indeed, it’s true that Republican-drawn maps in 2011 contributed to their candidates winning more than two-thirds of the collective House seats in Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Wisconsin despite losing the popular vote in each of these states to Democratic candidates.

But the problem isn’t really redistricting, so much as districting itself. Having one person represent 100 percent of people creates fundamental distortions that take on a harsh partisan character in modern America. The expanding Democratic coalition that boosted Obama — which includes racial minorities, working women, young people and socially liberal professionals — is heavily geographically concentrated. Even while easily winning the popular vote in 2012, Barack Obama carried only 22 percent of counties — far fewer than were carried by Michael Dukakis when he was trounced in 1988. Because every vote counts the same, that concentration evens out in the statewide presidential race. But in the House, which slices voters into districts, Democrats’ uneven dispersion of votes takes on great consequences — creating a natural partisan skew that commissions won’t erase and Republicans can easily exploit.

Winner-take-all also marginalizes voters. Not only do fewer than one in 3 Americans live in a battleground state in presidential elections, fewer than one in 10 will live in a meaningfully competitive congressional district in 2014. Moreover, few of these competitive districts represent the kind of voters who have played such a key role in Democratic electoral successes. To free voters from the shackles of geography, Congress and states should pass statutes enacting proportional representation based on voting for individuals, which already have been proven in local elections. In such a system, single-member districts would be replaced with larger “super-districts” where like-minded voters would elect representatives in numbers reflecting their voting strength. When Illinois used such a fair voting system for more than a century for elections to its state house, a quarter of voters in each district had the power to elect a candidate to represent them. As a result, nearly every district in every election chose a reflective balance of the Left, Right and center of its voters.

The path forward

For all the billions spent on winning campaigns and developing messages, center-left leaders have no agenda to adapt to the modern electorate by replacing our 18th-century electoral laws that marginalize and exclude most Americans with new approaches grounded in inclusion, participation and voter choice. When in power, Democrats in fact have generally embraced current laws as convenient means to protect incumbents, dominate opponents and shut down potential challenges from the Left. That failure of vision and abdication of principle has been a colossal mistake. It dilutes the potential of the changing American electorate and hands the power to block change to an angry, fearful Republican Party.

Going forward, Democrats should work with fair-minded Republicans to take the principled stand that they should have done years ago: enacting electoral reforms that maximize voter participation, voter choice and voter representation. Yes, their congressional incumbents from safe districts and state legislative leaders who enjoy monopoly control may complain, but parochial resistance from the status quo didn’t stop apartheid from collapsing or the Berlin Wall from falling. Movements for change can be compelling, particularly when the alternative is entrenched power that is willing to deny fair elections in order to suppress human progress.

The changes needed are many, including decreasing the influence of money in politics, but here is a package of reforms that would be fair for everyone and fully empower our changing electorate. It includes changes that Congress, states and cities can enact.

A National Popular Vote Plan for the Presidency: If Republicans decide to manipulate the Electoral College, Democrats — and all fair-minded Americans — have all the more reason to back the National Popular Vote (NPV) plan. NPV is an inter-state compact designed to guarantee the presidency to the candidate who wins the popular vote. Acting under powers granted to them under the Constitution, eight states and Washington, D.C. have passed the compact. Collectively, they represent nearly half of the 270 votes necessary to trigger a national popular vote in 2016. Each new legislative win at the state level will trigger more attention and bring us closer to the 270-vote threshold.

Once enacted by states with a majority of electoral votes, it will be activated and ensure that every vote will matter in every presidential election — freeing those orphan voters in the two-thirds of states that are now ignored and rendering moot any scheme to steal the Electoral College. Securing NPV by 2016 is tantalizingly close — and urgently needed.

Cities and States Shining a Beacon for a Constitutional Right to Vote: Recent state assaults on voting rights, potentially abetted by the Supreme Court striking down key provisions of the Voting Rights Act, demand an aggressive response. It’s time for a clear call for an affirmative right to vote in the Constitution and immediate action to expand voting rights. States can use new technology and existing databases to automatically register voters in a drive for universal voter registration. They can also invest in voter guides, better poll-worker training, and “public interest” voting machines that run on open-source software and are managed by nonprofits. Cities can take action to uphold voting rights and boost participation as well, particularly in states where new laws could disenfranchise voters. PromoteOurVote.org—a website run by my voting-rights organization, FairVote—has model resolutions detailing the full range of steps cities and states can take.

Ranked Choice Voting to End the Duopoly: The emerging majority doesn’t neatly fit into the simple partisan label “Democrat.” A growing number of young people are unaffiliated, and third parties remain attractive alternatives that are able to take principled positions and inspire the Occupy activists who want more than what Democrats are ready to deliver.

We can end the sectarian fight over the value of third parties through adopting the instant runoff system of ranked-choice voting (RCV) that allows voters to rank candidates in order of choice, then simulates a series of runoffs to determine the majority winner — thereby eliminating all talk of “spoilers.” Adopted by more than a dozen U.S. cities, RCV has a particularly strong base of support in Maine and Minnesota, which have strong third parties. In each of those states, RCV has proven successful in electing the mayors of major cities, while the lack of RCV in statewide elections has led to controversial outcomes and a string of victories by candidates who earned less than 50 percent of the vote.

Fair Voting for Legislatures, From Councils to Congress: Replacing winner-take-all, single-member districts may be the hardest lift, but is essential for representative democracy in today’s America. Super-districts with proportional representation provide a neat solution that can be established without a constitutional amendment. The question is how to get there.

In local and state governments, forward-looking leaders can simply move to fair voting plans. An interim step would be the Citizens’ Assembly plan pioneered by British Columbia. A randomly chosen citizen group was tasked with developing a proportional representation proposal that was then put before voters — where it won 58 percent, just shy of the arbitrary 60 percent threshold established for its enactment. Just as term limits swept the United States in 1992, a reform idea can be won far more quickly than many believe possible.

The Voting Rights Act creates another reform avenue. It has forced many jurisdictions with unfair winner-take-all plans to draw districts where racial or ethnic minorities can elect a candidate of choice. But the winner-take-all rules also mean that the majority of our nation’s African Americans live in Southern states with legislatures almost certain to be dominated by white, Republican conservatives for decades. It’s time for more state and local jurisdictions to use the Voting Rights Act to empower voters to win shared representation.

Winning fair voting for Congress requires overcoming the current Republican stranglehold and potential resistance from Democrats in safe seats. But sometimes the greatest need inspires the greatest movement for change, and congressional elections are more broken than ever. A diverse coalition outside Congress can push Congress members toward reform. Within both major parties, visionaries will see the value of having candidates be able to meaningfully contest every corner of every state. This is particularly true for those Republicans who see the need for their party to evolve with the changing electorate — and those who see that their party is increasingly captive to representatives from its strongholds.

Other likely allies include frustrated centrists who would earn a voice with plans that represent the Left, Right and center. Stalled at less than 18 percent of the House, women can embrace new systems likely to result in far more viable women candidates. Environmentalists would gain from having representation of a richer mix of voices from the rural West. Tea Party believers are just as interested in competing in Democratic areas as liberal Democrats are in Republican areas. And the list goes on.

For more than two decades, I’ve been told that fundamental electoral reform isn’t possible here. But I’ve seen exciting progress at the local level, and we can be closest to change when the times seem most desperate. Urgent needs create new allies and new openings. It’s time to expand our vision, embrace a true democracy movement and discover the new political world that awaits us.