Transnational Corporations, Factory Farms and the Economic Colonization of Rural America

John Ikerd

In 2011, Margaret Wheatley, a widely respected scholar and one of the leading thinkers in the United States on matters of institutional and cultural change, identified three major trends shaping U.S. society:

1) “A growing sense of impotence and dread about the state of the nation,”

2) “The realization that information doesn’t change minds anymore.”

3) “The clarity that the world changes through local communities taking action — that there is no power for change greater than a community taking its future into its own hands.”

I agree with Wheatley. Her revelations are more relevant to rural America today than in 2011.

First, I think “a growing sense of impotence and dread” accurately describes the prevailing mood of people in rural America. Fred Kirschenmann, a distinguished scholar at the Leopold Center at Iowa State University, has observed that the “predominant attitude toward rural communities is that they have no future. In fact, this attitude seems to prevail even within rural communities.”

He quoted from a 1991 survey conducted in several Midwestern rural communities indicating that people in most rural towns harbored one of two visions for their communities. “One vision sees their town’s death as inevitable due to economic decline.” The other vision is also of “a dying town” with only a fading hope that “they can keep the town alive by attracting industry.” The widening rural-urban divide since the early 1990s seems to confirm a transition in rural attitudes from impotence and dread to desperation and anger.

Secondly, I agree that information no longer changes minds, certainly not concerning issues such as global climate change, species extinction or genetically modified organisms (GMOs). For example, for decades the proponents of industrial agriculture called for decisions based on “sound science.” The early bits of research available on this controversial issue had come from the agricultural colleges — the academic allies of industrial agriculture. Now, a large and growing body of scientific information from other respected academic institutions provides compelling evidence of the negative ecological, social and economic impacts of industrial agriculture on rural America. The response of the “agricultural establishment,” and even the agricultural academic community, has been denial or rejection.

I agree also with Wheatley that any hope for a positive future for rural America depends on local communities taking action — rural people taking their future in their own hands. In order for people in rural areas to shape their own destiny, they must be willing and able to work together for the common good of their communities. But first, they must come to a common understanding and acceptance of the ultimate source or root cause of rural economic, social, and ecological degradation and depletion.

The economic colonization of rural America

The sense of impotence and dread in rural America is a consequence of decades of economic extraction and exploitation carried out in the guise of rural economic development. Rural areas are suffering the consequences of prolonged “economic colonization” — a term typically used in reference to neoliberal economic development in nations previously colonized politically. Rather than being colonized by national governments, most economic colonization today in rural America, and indeed in rural communities around the world, is carried out by multinational corporations.

Much like colonial empires of the past, transnational corporations have been extending their economic sovereignty over the affairs of people in rural places all around the globe. Rural people are losing their sovereignty, as corporations use their economic power to dominate local economies and gain control of local governments. Irreplaceable precious rural resources, including rural people and cultures, are being exploited — not to benefit rural people but to increase the wealth of corporate investors. These corporations are purely economic entities with no capacity for commitment to the future of rural communities. Their only interest is in extracting the remaining economic wealth from rural areas. This is classic economic colonialism.

A stripmine in the Montgomery Creek area of Perry County, Ky. (Photo / Caption: Geoff Oliver Bugbee / The Solutions Journal)

Historically, political colonialism was defended by the ethnocentric belief that the moral values of the colonizer were superior to those of the colonized — that those colonized ultimately would benefit from the process of civilization. Today, economic colonialization is defended by the urban-centric belief that rural people are incapable of developing their own economies and must rely on outside investment for rural economic development; that corporate investments will bring badly needed jobs and local income and will expand local tax bases; that economically depressed rural communities will be afforded the opportunity for better schools, better health care, and expanded social services, and will attract a greater variety of retail businesses. These are the same basic promises made to previous political colonies.

In general, people in rural communities are led to believe they have been left behind by the rest of society, and their acceptance ofoutside corporate investments is the only means by which they can hope to catch up. In cases where promises of prosperity have failed to persuade the people, corporations have resorted to economic favors promised to local leaders or outright “bribery.” If all else fails, they simply refer to commerce laws to claim the economic right to force their way into communities where they are unwanted. These are the same basic strategies colonial empires have used with the indigenous peoples of their colonies throughout history.

A British colonialist being carried on the backs of locals. (Image: quatr.us)

After decades of so-called development, previous political colonies were left in shambles. Indigenous social and political structures were destroyed, leaving the people with no foundation for reestablishing self-government to address the shameful legacy of colonialism. Traditional ways of life were destroyed, cultures were lost, economic resources were depleted, and natural environments were degraded and polluted with the toxic wastes of industrial extraction and exploitation.

Admittedly, in some cases, colonization has brought economic and social benefits — at least to some people. In these cases, such as North America and Australia, the indigenous populations were sufficiently small to be essentially eliminated by colonial immigrants. The people native to these countries were given a choice of assimilation or annihilation. The indigenous people of virtually every previously colonized country of the world, including the United States, still harbor deep resentment of their former colonial masters.

Like slavery, political colonization eventually became morally unacceptable to civilized society. It was abolished because it became obvious that colonization wasn’t about civilization; it was about exploitation. However, the economic colonization of rural areas continues virtually unchecked everywhere, including rural America.

Ironically, the rural descendants of past political colonizers have become the colonized: the unwitting victims of economic colonization. The European colonists first settled in rural America to exploit the economic wealth of its wildlife, timber, and minerals that had been left intact by Native Americans. Once the resources in particular places were used up or depleted of economic value, the exploiters moved on. Only “ghost towns” remained where many fur trading, logging and mining towns had once thrived. Today, many farming towns are struggling to survive and avoid becoming the new ghost towns of American history.

During the late 20th century, manufacturing plants were attracted to rural areas by a strong work ethic and low wages — a legacy of farm families displaced by agricultural industrialization. When rural people began demanding a living wage, multinational corporations found people in other countries who would work harder for less money. Many rural communities were left with only empty factories and people who no longer remembered how to make a living for themselves.

The cover story of the July 1, 1935 issue of Forbes asks “Who Own America’s Corporations?” (Image: Forbes Magazine Covers)

Whether intentional or coincidental, industrial agriculture has become a means of colonizing rural areas. As with other industries, the industrial practices of corporate agriculture invariably erode the fertility of the soil through intensive cultivation, and poison the air and water with chemical and biological wastes. Corporate contracts replace thinking, caring farmers with tractor drivers and hog house janitors. Once the resources of rural America have been depleted, the corporations will simply move their operations to other areas of the world where resources are more productive, and land and labor costs are cheaper. Rural communities will be left with depleted soils and aquifers, streams and groundwater polluted with agricultural chemical and biological wastes, and farmers who no longer know how to farm.

Today, rural communities compete for prisons, urban landfills, toxic waste incinerators, nuclear waste sites, animal slaughter plants and giant confinement animal feeding operations. All of these so-called economic development opportunities are nothing more than providing places to dump the human, chemical and biological wastes created by an extractive, exploitative economy. As in indigenous cultures of the past, the children of many rural families are abandoning rural communities for better economic opportunities and a more desirable quality of life in the cities.

This kind of rural economic development is economic colonialism — pure and simply. With today’s trend toward economic globalization, the corporate colonization of rural areas seems destined to spread to every corner of the world, until every remaining pocket of natural wealth has been extracted from every rural place in the world. This kind of rural economic extraction and exploitation quite simply is not sustainable.

The remnant rural populations who still cling to the indigenous rural American culture have every reason to harbor feelings of distrust, resentment and even hatred of the outsiders they identify with their oppressors. Like the remnant indigenous people of previous political colonies, they have fought long, costly, desperate battles to preserve their chosen way of life. They have survived thus far through fierce independence and self-reliance.

In defiance of urban culture, some rural folks have created their own version of an “affluent society,” with big 4×4 pickup trucks; jeans, hats/caps, boots and in-your-face country music. They eat giant hamburgers to show their disdain for “healthy eating.” They drink real beer from the big American breweries rather than boutique brews from local microbreweries. Wine is for sissies and liberals. Organic food is anything that grows. “Politically correctness” is rural profanity. They have their own RFDTV cable channel and rely on the FOX News network for a common version of political reality. The American Farm Bureau Federation is the ultimate authority on everything agricultural.

The lingering economic recession of nearly a decade, however, has taken at heavy toll on their hopes of sustaining a thriving parallel rural culture. The outsourcing of jobs following the Clinton-era “free trade” agreements hit rural areas particularly hard. Many remaining rural manufacturing jobs were low-skilled, low-paying, non-union jobs that were easily “exported” to Mexico or the Pacific Rim under “free trade” agreements. In rural America, NAFTA is a “four-letter word.” More recent environmental regulations, particularly those targeting species extinction and global climate change, have disproportionately affected rural economies that rely on extractive industries such as coal, irrigated agriculture, forestry and private use of public lands.

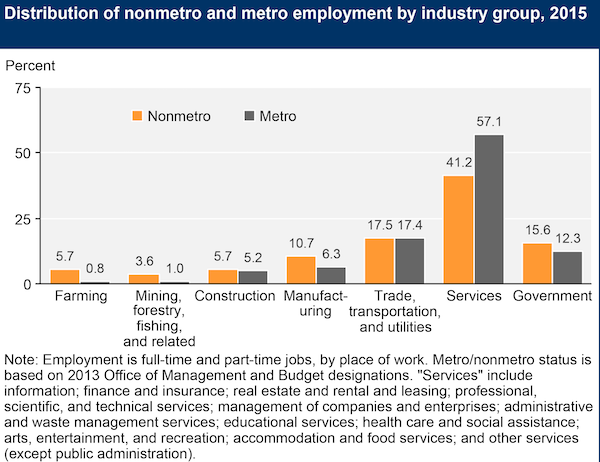

Industrial farmers have prospered in recent years, but farming is no longer a major source of rural employment, even in so-called farming communities. Farming accounts for only about 6 percent of non-metropolitan employment in 2014. Agricultural profits now accrue mostly to investors in corporate agribusinesses. The few jobs associated with extractive natural resource industries, such as fracking and coal mining, have gone mainly to outsiders who add little to the local economies of communities.

Rural or non-metropolitan employment overall has recovered far slower than metropolitan employment since the recession of 2008, leaving rural employment well below levels of 10 years ago. The fierce independence and defiance of rural people is being severely tested by the current economic and political environment.

(Infographic: USDA Economic Research Service using data from Bureau of Economic Analysis)

Wendell Berry summarized the current plight of rural America in a recent letter to the editor of the New York Review of Books: “The business of America has been largely and without apology the plundering of rural America, from which everything of value — minerals, timber, farm animals, farm crops, and “labor” — has been taken at the lowest possible price. As apparently none of the enlightened ones has seen in flying over or bypassing on the interstate highways, its too-large fields are toxic and eroding, its streams and rivers poisoned, its forests mangled, its towns dying or dead along with their locally owned small businesses, its children leaving after high school and not coming back. Too many of the children are not working at anything, too many are transfixed by the various screens, too many are on drugs, too many are dying.”

There are good reasons for the growing sense of impotence and dread and even anger, in rural communities. In desperation, some indigenous rural Americans are fighting back by all possible means — in what might be their “last stand.”

The above excerpt was taken from a keynote address John Ikerd delivered at the 2017 Rural Sociological Society Annual Meeting, held July 27-30, in Columbus, Ohio. The focus of the RSS’s 80th annual meeting was Rural Peoples in a Volitile World: Disruptive Agents and Adaptive Strategies. To read this presentation in its entirety, click here. To subscribe to John’s blog visit johnikerd.com. (Image: ruralsociology.org)

This work is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the author.