The Grouse That Roared: Will Voluntary Conservation Efforts Work in the Intermountain West?

Kendra Pierre-Louis

Asking a rancher how many acres she has is like sidling up to a stranger and asking her how much she gets paid — it’s intimate and rude. Acreage is money — the more land you have the more cattle you can run — a fact I’m only told after we, a group of roughly 20 journalists, have made a group of ranchers confess their acreage.

Over a lunch of brisket, courtesy of local grass-fed cows, each rancher’s story unfurls in much the same way: with total acreage usually in the thousands, and then, when prodded, a breakdown based on leased Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land versus their privately owned acreages. It becomes subtly evident that they view the BLM land as their own although legally it’s public land leased for the public welfare. The checkerboard pattern which intercuts private land with public land, however, makes that distinction fuzzy, except in one critical way. Here in the arid intermountain west the private land has most of the water, as much as 70 percent by some estimates.

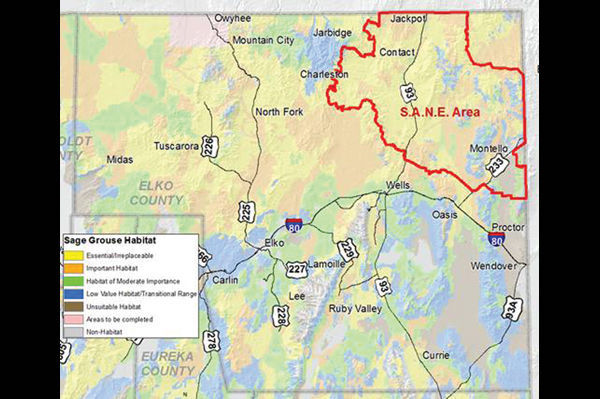

The ranchers subjecting themselves to this odd interrogation are members of Stewardship Alliance of Northeastern Elko (SANE) which member Robin Boies says, “Uses conflict management, a facilitated collaborative process, and sustainable agriculture techniques to improve habitat health while creating a new mythology for the west based on civil dialogue and long term solutions.” It’s a refreshing perspective coming just six hours north of Cliven Bundy country. SANE isn’t here to talk land, however, they’re here to talk sage grouse. But you can’t extirpate the sage grouse from the land and expect either to do well.

The SANE alliance consists of 8 ranches in northeastern Elko Country, Nevada. (Image: elkodaily.com)

To list or not to list

The greater sage grouse, the largest grouse in North America, is a close relative of turkeys, quails and chickens. The thick-bodied, clunky fliers once numbered in the millions, blotting out the sun as they flew. Today, between 200,000 and 500,000 birds remain—an estimated decline of 97 percent from a century ago and 30 percent since 1985.

In a 2011 settlement with environmental groups, the Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) agreed to determine within four years whether the sage grouse warrants listing under the Endangered Species Act. If the sage grouse did not get listed, some feared the bird would go extinct. Yet listing itself offers no panacea: The northern spotted owl has been on the list since 1990 and its population continues to decline. The decision impacts at least 165 million acres across 11 states — California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington and Wyoming — that make up the sage grouse’s domestic range. As a result, the bird’s fate became a political football, with legislators as well as the agriculture and oil-and-gas industries, attempting to block the bird’s listing. In December 2014, Congress voted to withhold funding to implement any listing, which Western lawmakers say could limit the region’s avenues for economic development.

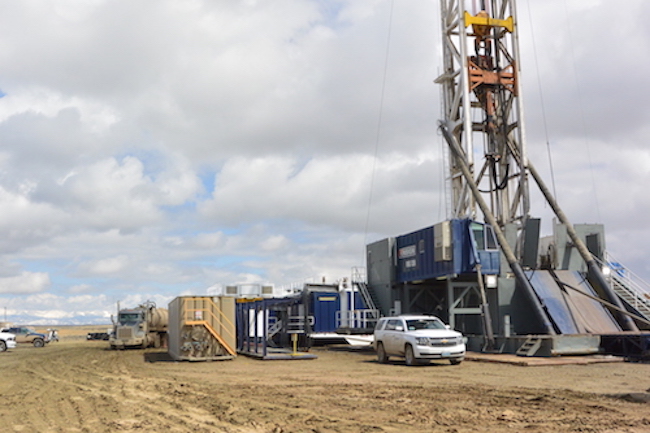

At the same time, states have poured millions of dollars into habitat protection, ranchers have altered ranching practices, fracking sites refrain from drilling near breeding grounds and wind sites have been redesigned — all to avoid impacting the sage grouse and avoid the need for listing.

These efforts have seemingly worked. On September 22, the FWS announced that it had determined the sage grouse did not require greater protection as a threatened or endangered species.

Before the decision came down, opposition to federal intervention on the sage grouse ran high out West. Nearly everyone I met wanted the sage grouse saved, but not placed on the endangered species list. State and federal agencies poured millions into voluntary conservation efforts. This coordination isn’t perfect. While the BLM, in collaboration with other agencies, is implementing a sweeping sage grouse conservation strategy on federal lands, it appears set to approve an energy project that could undermine these efforts. The proposed route for a 730-mile transmission line—which would run from Wyoming through Utah to Nevada carrying wind energy to the three states along with Arizona and California — cuts through the heart of key, relatively undisturbed sage grouse territory.

Still, “people who have fundamentally disagreed for 20 years are coming together in partnership to protect this habitat,” says Brian Rutledge, Vice President for Strategy and Policy of the National Audubon Society and Central Flyway Conservation. Whether that collaboration will continue without the threat of a listing, or whether a listing would fracture that collaboration, is difficult to know.

On his land in Moffat Country, Colorado, rancher Wes McStay (left) speaks with Brian Rutledge from the National Audubon Society. (Photo: Kendra Pierre-Louis)

In a press briefing, Department of the Interior Secretary Sally Jewell stated that the decision not to list the bird was a result of, “the largest, most complex land conservation effort in U.S. history, perhaps the world,” before noting that, the decision not to list would anger both sides of the aisle, “Some people are going to say that the bird should have been listed, these plans don’t go far enough for the sage grouse, and others will say the plans are worse than a listing you’re going to lock up development forever.”

Minamizing the destruction of habitat

Sage grouse thrive on some of the driest and coldest, yet most starkly beautiful land in the country: the sagebrush ecosystem. It’s the iconic West: big sky country with looming mountains, as synonymous with cowboys, ranching and mining as it is with bison, mule deer and sage grouse.

Ranching is frequently criticized for hurting the land. Cattle are picky eaters who, if left to their own devices, will strip a pasture of everything tasty, leaving behind a less diverse ecosystem with less food for other animals. If too many cattle are put on a pasture and left for too long, they’ll leave it completely denuded and open to opportunistic species like cheatgrass, an invasive grass that pushes out the native sagebrush the grouse need to survive.

Cheatgrass starts growing earlier in the season than most other plants and its fibrous root system sucks up water faster than native, perennial grasses. It’s also incredibly flammable. Cheatgrass is at least partially to blame for the increasing frequency and intensity of fires in the West.

[If you like what you are reading, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the wolf on the upper right of your screen.]

Once you can identify the seemingly innocuous wheat like stalks of cheatgrass you begin to see it everywhere in the intermountain west: in fields, peering out between stands of sagebrush, along the highway, but not on Boies Ranch, a cattle ranch two hours southeast of the casino town of Jackpot, Nevada.

It’s just after sunrise one Sunday morning in April, the air still has the bite of an early morning chill and a rancher drives me past wire fence lines marked every three to four feet with 4-inch pieces of white plastic. Sage grouse frequently fly to their death by colliding with the barbed wire fences that corral livestock. These markers make the fences visible to the sage grouse and a 2010 study funded by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game found that they reduce sage grouse mortality by 83 percent.

A marked fence delineates land in sage grouse territory. (Photo: Kendra Pierre-Louis)

Robin and Steve Boies work hard to ensure their ranching practices are within the ecological limits of their land. They keep the size of their herds at a level that the land can support, grazing half the ranch at a time and resting the other half. They even employ cowboys to ensure the cattle stay where they’re supposed to, with the added benefit of keeping predators like coyotes away. The goal is to keep ranching while also protecting the land.

“In the 1980’s when we started this,” says Robin Boies, “we were in an absolute war with the BLM over grazing. But it doesn’t do my soul to be in conflict.”

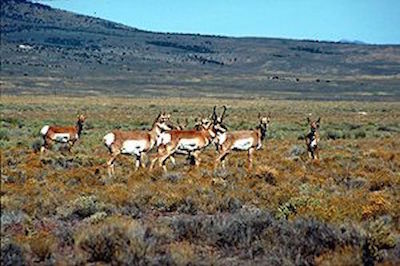

Despite the opposition to cattle ranching by some environmental organizations, like the Western Watersheds Project, many ecologists no longer have a problem with ranching when properly practiced. Herbivores have always existed on grasslands, and a growing body of data has shown that appropriate grazing can improve wildlife habitat and plant species diversity. On the ridgeline, dots reveal themselves to be a herd of pronghorn, the fastest land animal in North America and the second fastest animal in the world. They’re the sole surviving descendants of an ancient family dating back 20 million years. Much of their range overlaps with that of the sage grouse, and like the sage grouse its numbers too have dwindled. Two subspecies, the peninsular pronghorn which resides in Baja California, and the Sonoran pronghorn which sticks to the Arizona’s Sonoran desert, are on the endangered species list. But here, cheatgrass seems far away and the sprawl of craggy hills is stippled with sagebrush.

A herd of Nevada pronghorn. (Photo: blm.gov)

The sage grouse’s last dance?

Sagebrush is a low, unassuming scrub bush. But its tiny stature conceals a long life span. Sagebrush that stands at toddler height can be a century old. Pat Deibart, National Sage Grouse Coordinator for the FWS, puts it this way, “The sagebrush is an old-growth forest that’s 24 inches high.” The plant’s taproots pull up water from deep in the soil while its brush traps and holds windblown snow on the land in the winter, providing crucial water for plants come spring.

The sage grouse is named for the sagebrush because it needs sagebrush to survive. In spring, the grouse hide their eggs in the brush. In summer and fall, the brush provides camouflage from predatory birds, and the moisture held by the plants attracts the fat insects that are crucial to sage grouse hatchling’s diet. When winter comes, the sagebrush not only offers protection from harsh winds and temperatures that can dip to below 40 degrees Fahrenheit, but also provides sustenance. Sage grouse thrive on a winter diet comprised exclusively of sagebrush.

As the sagebrush ecosystem is destroyed, so too are the grouse. A century of harmful human impact, from ranching to mining to oil and gas drilling, has put that ecosystem at risk.

In ancient times, the morning hours between three and four were called the witching hour because it was then that witches, demons and all matter of supernatural beings awoke to spread their malevolence. But for a few months each spring outside of Craig, a town of roughly 9,000 people in northwestern Colorado, that delicate hour become the lekking hour. Leks are sage grouse courting grounds where males — easily identifiable by their peacock-like plumage and thick, chichi collars of white feathers — stamp their feet, gyrate their heads and puff up their yellow chest bladders to make a distinctive popping noise. This ultimate in avian mating dances is called the sage grouse strut.

The best viewing hours are just after sunrise, but the distinctive popping noise can be heard even in the pre-dawn darkness as we walk the mile or so between where the trucks deposit us and the bird blind which provides an intimate viewing experience without disturbing the grouse. We’ll sit in total silence until the grouse take off for the day to rest, and feed before giving it another try the next day. Most of the males will never copulate, leading researchers to dub the lothario who gets most of the ladies ‘the master cock.’ When the blind lifts, the scene that unfurls before us is surprising — the land in front of us isn’t pristine sagebrush but a groomed field.

Every spring for five years, Wes McStay has allowed the nonprofit organization Conservation Colorado to run lek tours, like this one, on his ranch in Moffat County. This kind of access is important because much is still unknown about the sage grouse and leks allow researchers to calculate their populations. By some estimates more than 80 percent of leks are on private lands.

“Sage grouse have extreme site fidelity,” says Deibert. Across the west, sage grouse will try to renest regardless if a habitat’s suitability has changed. Famously, there’s a lek at the end of the Jackson Hole Airport runway in Wyoming. This site fidelity is risky, since it not only impacts the how often birds mate on a lek, but also how long those eggs and chicks survive since sage grouse hens nest near leks.

When a fracking field is built near a lek — as in the case of the Jonah Field, a natural gas field in Sublette County, Wyo. — it directly impacts the health of the sage grouse. On the Jonah Field, a sprawling 300,000 acres — 80 percent of which is public Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land leased for the public welfare — the noise and light interfere with the birds’ ability to mate and communicate. Both the holding tanks that dot the property and the transmission lines that bring power provide perches for ravens and crows, from which they can find and raid sage grouse nests. There were once four leks on the Jonah Field, but only one is still active.

The Jonah natural gas field in Sublette County, Wyoming. (Photo: Kendra Pierre-Louis)

Thirty-seven percent of all sage grouse live in Wyoming. That is not coincidence. Wyoming has the fewest people per square mile outside of Alaska and there’s a strong correlation between the number of people in a state and how healthy the sagebrush, and by extension the sage grouse, is. Humans have a knack for destroying the sagebrush ecosystem.

Paul Ulrich, Jonah Energy’s regulatory director tells us, “Wyoming is a great place to hunt, and fish and poke around on my mountain bike. I plan on raising my kids here and I hope they can raise theirs here and have what I have.”

But it’s doubtful that his grandkids will have what he has.

Over the past 25 years, the West has had the greatest population growth in the country. From 1990-2000, Nevada, Utah, and Colorado population increased more than 25 percent in comparison to the national average of 13 percent. From 2000-2010 these states continued to grow rapidly — more than 10 percent a year, with Wyoming one of the least populous states, which spent most of the late 20th century losing population, also grew.

When a species is at risk of extinction we tend to look for easy causes. But in the case of the sage grouse a single cause remains elusive. It’s the sum total of human beings’ imprint on the landscape: a century of bad ranching practices, the impact of oil and gas extraction, mining, human developments and the bird killing cats we bring with us that are harming the sage grouse. And it’s not just the sagebrush ecosystem that’s imperiled. Many scientists believe that, thanks to human activity, the Earth is in the midst of its sixth mass extinction. (The fifth occurred 65 million years ago, when the dinosaurs and 75 percent of life on earth were exterminated by an errant six-mile wide asteroid.) Normally, the process of extinction is quiet. Who mourns the last known Christmas Island Forest Skink, a smooth-bodied, speckled lizard named Gump who died late last year? What’s surprising about the sage grouse is not its decline, but that we’re noticing it.

It’s why Secretary Jewell, though satisfied in her pronouncement that the decision not to list the bird meant, “a brighter future for one amazing scrappy bird that calls the West home,” also noted that the announcement was also merely the end of a beginning. “We need to implement these state plans and these federal plans,” cautioned Jewell, “and keep learning about what’s working on these landscapes, and we need to incorporate science in our decisions into the future.”

“People say, ‘The grouse are so stupid,’” says Rutledge, in reference to the fact that we are talking about a bird that will return to a mating site regardless of its current suitability and has a tendency to fly into fences. “But they’ve been doing pretty well for 40 million years in a habitat we’ve all but decimated in 100 years.”

A sage grouse takes flight in Moffat Country, Colorado. (Photo: Kendra Pierre-Louis)

This reporting was made possible by a grant from the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources.