Language of the Unheard: 50 Years On, the Flames of the Detroit Uprising Still Burn

The structural injustices that laid the groundwork for Detroit’s uprising still exist.

In These Times Staff

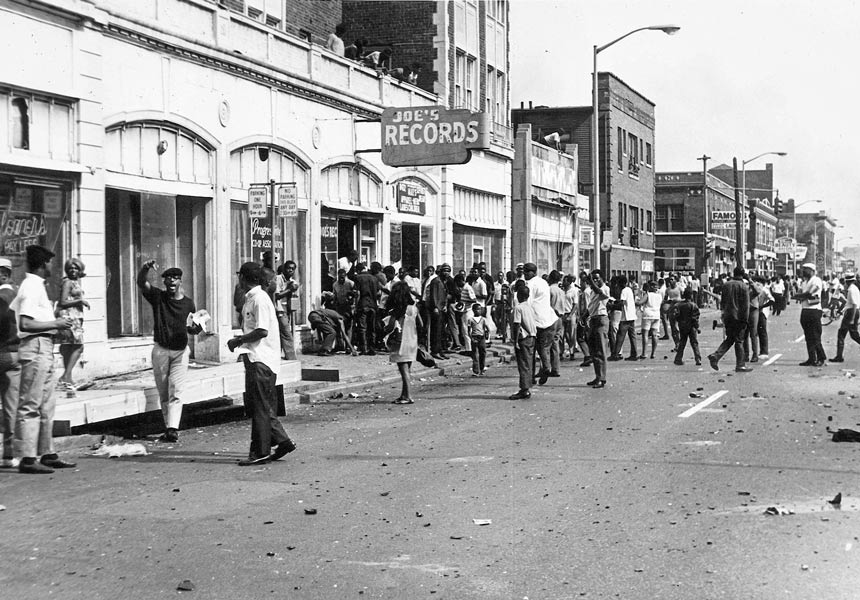

Early on the morning of July 23, 1967, police in Detroit raided an illegal after-hours bar and began to arrest all 85 people there. A crowd gathered, and, soon, allegations of police brutality were flying — along with bottles and rocks thrown by fed-up Detroiters. Over the next several days, 2,509 buildings were damaged, 7,231 people were arrested and 43 died, most of them killed by police or the Michigan National Guard.

Fifty years later, the structural injustices that laid the groundwork for Detroit’s uprising still exist. Oppressive police forces, widespread poverty and housing segregation pervade U.S. cities, and citizens are again in the streets. The excerpts below are taken from Detroit 1967: Origins, Impacts, Legacies, a new collection edited by Joel Stone of the Detroit Historical Society.

The following excerpt comes from the book’s foreword, written by native Detroiter Thomas J. Sugrue, professor of history at New York University.

Detroit’s 1967 riot is conventionally portrayed as a moment of collective lawlessness and disorder or as an irrational outpouring of rage. Those descriptions are woefully inadequate. The events in late July were an outgrowth of years of protest. To use the contested language of the 1960s, black Detroiters engaged in an uprising against a racially unequal status quo, a rebellion against brutal police and exploitative shopkeepers. There is no evidence that the burning, looting and vandalism that happened on the city’s streets in July 1967 was organized, despite pervasive conspiracy theories that outside agitators, whether communists or advocates of black power, had orchestrated the riot. But there is abundant evidence that many of those who took to the streets saw their actions as a challenge to the legitimacy of white authorities. Many of the participants in the 1967 riot took the opportunity to exact revenge for economic hardship. Looters singled out merchants, especially owners of food stores who routinely overcharged their inner-city customers. Some saw looting as redistributive justice.

Like all rebellions, Detroit’s had unanticipated consequences. Few who took to the streets had a vision for what the post-riot city would look like. In the aftermath of July events, Detroit’s civic leadership — for a time — channeled money into community economic-development projects. Foundations sponsored job training and creation programs. City officials haltingly implemented programs to diversify the public employee workforce, even though they faced fierce resistance, especially among the city’s overwhelmingly white police force. But the long, hot summer also fueled an already intense, bipartisan demand for tough “law and order” politics, including militarizing police departments and expanding the prison system. The fallout from the urban uprisings also gave whites who had long fiercely opposed housing and educational integration a new justification for keeping blacks out of their neighborhoods and schools. Half a century after 1967, Detroit remains near the top of the list of America’s most racially divided metropolitan areas. Many whites continue to rally around calls for tough policing and continue to discount African-American grievances as special-interest pleading.

Fifty years after Detroit’s uprising, the events of 1967 are sadly relevant. The protests in Ferguson, Mo., after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown; the burning and looting in Baltimore in the spring of 2015 after the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody; the anti-police-brutality marches in violent Chicago in 2016; and the uprisings in Milwaukee and Charlotte, N.C., in August and September 2016 are all reminders of the fact that many of the underlying causes of the long, hot summers of the 1960s remain unaddressed.

Above: Detroiters loot a record store on 12th Street, part of an ebb and flow of activity that confused officials attempting to determine appropriate countermeasures. (Detroit Historical Society Collection, reprinted with permission from Wayne State University Press)

Above: Federal troops of the 82nd Airborne Division were shuttled by chartered buses to various staging points near the conflict zones. (Image courtesy of Thomas Diggs, all images reprinted with permission from Wayne State University Press)

From “The Problem Was the Police,” by Melba Joyce Boyd, professor of African-American studies at Wayne State University:

Karl Gregory, a community activist and a professor at Wayne State at the time, described his encounter with the National Guard in July 1967 during an oral history session with the Detroit Historical Society.

It occurred on the east side of Detroit when he was patrolling the streets with Alvin Harrison, trying to get people to return to their homes during the civil eruption. We continued until late that evening during a curfew. The National Guard stopped us. There was a young white guardsman who dismounted from his vehicle, approached, and told me, “Pull your window down.” I was driving. [He] pointed his gun at me. I was concerned, but I wasn’t afraid then. His hand was shaking … on the trigger. And I said, “Look, I’m a college professor. I am just trying to get the people off the street.” And he looked like he was trying to determine whether or not I was a rioter (or what have you), and a sergeant came by and said something like, “Cool it.” But this guardsman [the kid] was more afraid of me than I was of him. I don’t know how many black persons, if any, that youth had been in contact with before in his entire life.

Above: Detroit Free Press staff entered the conflict area in an armored personnel carrier loaned to the newspaper by the Chrysler Corporation. They included (left to right) copyboy Tom De Lisle, photographer Ira Rosenberg and reporter Gene Goltz. (Timothy Kiska and the Detroit Free Press, reprinted with permission from Wayne State University Press)

From “Hindsight: The Shift in Media Framing,” by Casandra E. Ulbrich, vice president for college advancement and community relations at Macomb Community College in southeast Michigan:

Ask any native Detroiters old enough to remember about their reflections on the “Detroit riot” and you are likely to hear vivid memories of burning buildings, tanks in the streets, or neighbors protecting one another’s homes. They will tell you about the smell of the smoke, the crackling of breaking glass, or the fear that comes from the unmistakable sound of gunfire in the distance.

But you are also likely to hear a refutation of the word riot. “It wasn’t a riot,” some will tell you. “It was a rebellion.” And just like that, the images just described assume a completely different meaning. The actions of those who were involved are transformed, as are the actors themselves. The historical context is redefined, and societal responsibility suddenly becomes part of the discussion.

Copyright © 2017 Wayne State University Press, with the permission of Wayne State University Press