In the American West, Arbitrary Poverty Designations Are Shortchanging the Rural Poor

Elizabeth Zach

Two years ago, Consuelo Andrade was living in a village with her grandparents in Michoacán, Mexico, where she regularly saw neighbors and acquaintances returning from time spent working in the United States. Their clothes were classy; some drove cars. She was mesmerized. No one, however, spoke about the work up north, and what it took to earn and save to buy such impressive goods.

Manuel Andrade was one of the men who returned to Michoacán. He eventually asked Consuelo to marry him and return to Tulare County, Calif., where he has picked oranges since 1979. Like countless immigrants before her, she expected, if not fortune, then certainly a better, more prosperous life in California than the poverty she knew in Mexico.

What she found was not quite what she envisioned.

Consuelo wears bright blue sweat pants, an olive green sweater and a bandana tucked back with bobby pins. At age 39, she appears weary. But at the sight of visitors, her smile is immediate and she ushers them into her yard. Her home is like all the others here on Road 216 in Tonyville: crumbling paint, shaky floors and stairs, gravel and weeds, dead tree branches, laundry lines, and plastic sheeting over windows to cut down on the drafts. Like many families in the Central Valley, the Andrades rely on bottled water for household use, due to nitrate contamination in the water that comes out of the tap. But the rent is affordable at $400 per month.

The language, the pace of life — it was all so strange, so disorienting, recalls Consuelo about her arrival in 2016. Picking oranges day in and day out has gotten easier, she says, now that Manuel bought her a ladder. She can fill up to three boxes with the fruit from eight trees. Ordinarily, she and Manuel would each earn $88 per day at the California minimum wage of $11 per hour, but with increasing vision problems and associated doctor visits, he only works half-days, compounding their economic fragility.

Neither Manuel nor Consuelo have heard of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, so they wouldn’t know that the author set much of his tale right here in Tulare County. Next year, it will be 80 years since the book was published. Manuel has been here 40 of those 80 years, just like the countless second- and third-generation Latino farmworkers who make up a critical component of California’s economic backbone. They work long, hard hours, uncomplaining as they feed the state and the nation. Yet their income does not keep pace with ever increasing expenses, despite the fact that the minimum wage law governs their monthly incomes.

Why the federal government’s varied definitions of persistent poverty matter

The U.S. Census Bureau reported in July 2016 that Tulare County’s poverty rate is 24.7 percent. Twenty percent is considered high.

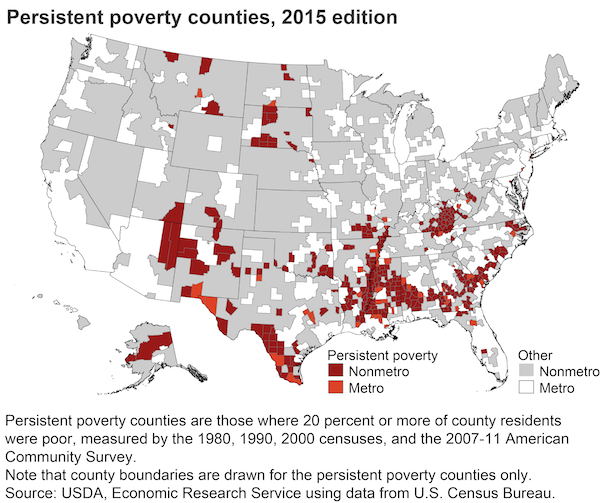

The government uses census data to define counties as officially “Persistently Poor” if 20 percent or more of their populations were living in poverty during the last 30 years, as measured by the 1980, 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses and the Census Bureau’s 2007-2011 American Community Survey. The definition affects at least 15 different spending programs within the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Education, Labor, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Transportation, the Treasury and the EPA.

This federal funding translates into life staples: wastewater systems and clean water delivery, decent low-income housing, literacy programs, economic development, roads and telecommunication infrastructure. The USDA, for example, has a mandate for 20 percent of its lending to go to persistent poverty areas. In addition, the new tax law creates “Opportunity Zones,” but this is based on census tracts, not counties. States can designate 25 percent of their “high need” census tracts as these opportunity zones, which translates into significant tax benefits to encourage investment there.

Today, there are 353 persistently poor counties in the United States, of which 301 are rural, and the rest urban. Eighty-four percent of persistent poverty counties are in the South. Much of Appalachia qualifies. In the West, 21 rural (non-metro) counties are officially designated as persistent poverty counties. Moreover, agencies adopt new definitions over time. The USDA’s definition is not the same as HUD’s, and the one at HHS differs from the Treasury’s criteria.

Though persistent poverty designations are changed and updated regularly, not a single rural California county qualifies. The reason, say experts, is that many of the state’s rural poor don’t actually live in rural counties. Instead, the state’s large counties often include higher income urban populations that hide substantial rural areas where persistent poverty exists — like Tulare County, which is an urban county.

Likewise, Fresno is an urban California county based on population. But the county also has sizeable rural census tracts, west of the city of Fresno, that are persistently poor.

Isolated geographically, neglected and shrouded from mainstream America, these areas lack resources and economic leverage. They have suffered from decades of disinvestment and high poverty rates. In short, because the government defines poverty by the county as a whole rather than by individual census tract, they are denied access to funding and programs that could help.

“Persistent poverty has always been measured by county and because of that, the federal government has been reluctant to consider other options,” says Janice Waddell, who was State Director for Rural Development California for the U.S. Department of Agriculture between 2015 and 2017, and prior to that worked for 35 years within the agency. “That really puts California at a disadvantage when our rural poverty is very considerable. It excludes so many populations and doesn’t reflect what’s happening on the ground. A persistent poverty county can access more funds, or get first shot at funding when there are initiatives that come out to target high poverty areas. California is disadvantaged because it often cannot compete for those funds.”

Moreover, when the cost of living in California is measured against median household incomes, the state is the poorest in the nation, despite its stellar job and economic growth. More than 20 percent of its residents — 8 million people — are struggling to pay bills, according to the U.S. Census’ supplemental poverty measure, which takes into consideration food, housing, taxes and medical costs. Last year, these striking figures prompted California State Assembly Republican Leader Chad Mayes, who represents San Bernardino and Riverside counties, to declare poverty California’s most urgent priority.

An on-the-ground look at persistent poverty in two states

In January, I spent a few weeks in rural California and New Mexico to try and better understand how these federal poverty guidelines affect residents — and in particular at a time when the overall urban economy is booming and unemployment is down. In California, in addition to Tulare County, I visited Fresno and Riverside Counties. In New Mexico I visited two counties — Taos and Dona Ana. These five counties have similar economies and demographics; all five have significant Hispanic populations, all have vast rural areas and all struggle with drought, contaminated water and lack affordable housing. The difference, however, is that the New Mexican counties qualify for persistent poverty status, allowing them access to funding and anti-poverty programs.

On Avenue 66, between La Quinta and Thermal in California’s Riverside County, Steinbeck’s prose comes to life. Here, along a corridor of date palms lining the road, there is a somewhat Middle Eastern regal ambience. Driving it, you may expect to end up at a desert palace. Indeed, traveling westward, that wouldn’t be far off the mark: La Quinta’s lush world-class golf courses and manicured yards and homes behind automated gates are an oasis set against the striking Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains.

But drive just a few miles eastward and you will pass lettuce fields and orange orchards, and cadres of laborers among each, fully covered to shield themselves from sun and farm chemicals. Eventually you will reach the decrepit mobile homes scattered along unpaved roads and see dilapidated trailers behind metal fences, shrouded by drying laundry and abandoned cars, a world away from Palm Springs and La Quinta.

Samuel Castro has lived in Thermal for nearly four decades. It was poor when he arrived from his native Michoacán and it’s without question still poor. He speaks no English — he explains, he was too busy working in the fields to learn. But he’s moved up a bit in this world: for the past 15 years, he’s owned and managed the 12 mobile homes at the Mezquit Mobile Home Park in Thermal. Walking among the homes, he describes trying to convince residents to get rid of old cars that no longer run and are left blocking fire routes. There are no sewer lines to his park; he must manage a septic system. He details the county fees and permits that have left him drowning in debt, and problems with the former owner who refused to vacate the property. He’s scared, he doesn’t want to speak ill of the bureaucracy; he doesn’t want to jeopardize his lot.

Instead, Castro does the best he can, walking the premises daily to inspect the properties and make sure all is up to code and pleading with tenants to remove unused cars and do their part to keep the area presentable.

Some 350 miles north of Thermal, in Fresno, Dave Herb has spent his adult life puzzling over situations like Castro’s and generational poverty — ever since he arrived in Kings County, Calif., as a VISTA volunteer in 1969. Back then, he says, “I thought to myself, ‘God must not love this place.’”

A Pennsylvania coal country native, he says he came to California “to save the poor” and “to teach people how to be squeaky wheels.” He eventually settled in Fresno where he raised a family and worked for decades in county politics. He has an unmistakable affection for his adopted home, in particular when he notes proudly that the writer William Saroyan lived his entire 72 years here and, even as an older gentleman, could be seen pedaling his bike around town.

He has watched prisons — a dozen today — proliferate throughout the Central Valley, California’s 450-mile long agricultural powerhouse that parallels the Pacific Ocean and the Sierra Nevada. The prisons provide jobs, but also mutate the fabric of cherished farming communities and increase suburban sprawl. He has watched neighborhoods diversify and gentrify and develop.

“The Central Valley is a classic case of establishing scattered communities without adequate services,” says Herb, as he drives through Calwa, a low-income Fresno neighborhood. “Over the years, counties here have allowed scattered developments often without adequate levels of urban fire protection, police or infrastructure.”

These communities were often built on unincorporated land, Herb says, and the development standards on that land, “were much, much lower than they are in cities. There were no requirements for street lights, sidewalks, paving, gutters, they often had no community water systems, and many relied on private wells.”

The history is different for every community, he explains. The scattered nature of the development was sometimes due to farming and agricultural needs, but not always.

The western half of Fresno County is very poor and has been so for decades. But further east around Fresno, it’s somewhat more prosperous. The USDA, which could provide the most funding Fresno County’s rural areas, such as deeply impoverished communities like Mendota and Firebaugh, does not recognize it as a persistently poor county. Nor, for that matter, does it recognize it as a rural county.

A rural New Mexico community considers its options

On a sunny yet freezing Saturday afternoon in Rio Lucio, a town in Taos County, Melanie Delgado sat among more than a dozen area residents in a trailer that serves as the Rio Lucio Community Center. Sitting on metal folding chairs around tables forming a crescent moon, some participants sipped from water bottles, others from Styrofoam cups filled with ginger ale.

The meeting agenda was focused on but one item: water.

As a community services coordinator with the New Mexico Environment Department’s Drinking Water Bureau, Delgado spends her days helping rural communities figure out how to deliver clean water to residents and businesses and how to treat wastewater. She also helps them determine whether they are eligible for grants that would cover their infrastructure costs and pay for certified water operators, who are trained to ensure clean water delivery and manage wastewater systems.

So she knows better than most the issues of drought and contamination plague this mountainous region. In the month prior the meeting, one water system had three major water leaks. Another system, at an elementary school, drained 250,000 gallons of water over twelve hours; no one could find the valve to stanch the flood. Some communities around here don’t have water operators; there’s no economy of scale and infrastructure is expensive. The one bright spot, everyone agrees, is that local leaders are sympathetic to keeping rates low, recognizing that this is a low-income county.

“Well, it is and it isn’t,” Delgado said after the meeting as she helped fold and stack the metal chairs.

Here in Taos County, the median household income is $31,112 and the poverty rate reported in July 2017, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, was 22.4 percent But Delgado says the median income figure may be misleading. The city of Taos, with its world-renowned art galleries and nearby ski resorts, is a haven for the wealthy. Julia Roberts has a seasonal house there. Robert Redford calls Taos home. (In fact, it’s also where Redford filmed his 1988 Milagro Beanfield War, which is set in a poor northern New Mexico town that loses its water to political and business interests.)

The county’s historical poverty, however, has earned it persistent poverty status, which allows it to compete for rural development funding. Such funding helps towns like Rio Lucio and nearby Peñasco and Rodarte, which continue to struggle with paying for clean water.

Nearly 500 miles south of Rio Lucio, the high desert gradually flattens, allowing farmers in Dona Ana County to grow the area’s signature chili peppers. The Hatch Chile Festival on Labor Day weekend attracts more than 30,000 visitors from around the world to the town of Hatch, population below 2,000, earning it coverage in the BBC and Food Network. But for most of the year, this is a lonely, searing landscape.

It’s all Lisa Neal has known, growing up here on her parents’ onion farm. She has a natural affection and enthusiasm for Hatch, serving as its library director as well as the Hatch Valley Economic Coordinator.

One afternoon during my visit, she drove through a neighborhood where farm laborers live and which are similar to those in California’s Central Valley. Both stretched amid dusty roads and were populated with wire fences and makeshift trailers. Neal later pointed to an arroyo that flooded over levees in 2006 and last year, and she described the water and wastewater problems Hatch has had to deal with across periods of extreme drought and flash flooding. But because of Dona Ana County’s persistent poverty status, it qualified last year for more than $500,000 in USDA funding to renovate its water system.

“We’re eligible for certain library programs, too,” Neal said, explaining the poverty she has observed in Hatch over the years. She receives increased state funding for bilingual books and to teach citizenship, GED and literacy classes. Funding for this is partly through the federal Library Services & Technology Act, which supports libraries in underserved rural communities and children from families with incomes below the poverty line.

One of those children was Ana Balcazar, whose family arrived in the Hatch Valley nearly 30 years ago. Her father was 13 when he came; now 40, he and his wife are raising five children. A number of their family members work for Lisa’s sister, whose husband has a farming business. As soon as Ana was old enough — age 12 — she, too, was in the fields. She is now 18.

“We picked onions and I learned how to top off their stems,” she says. “It was hard work. I knew it then even though I had nothing to compare it to. My father would make a game out of it for us and we’d have competitions to see who could do the most work. During the summer, we’d be up at 4 a.m., start work at 5:00 a.m. and finish sometime in the afternoon. My grandfather is in his 70s and he’s still working in the fields.”

In 2016, Balcazar applied for, and got, a part-time after-school job at the library. She learned how to shelve books, helped visitors use the computers and translated for those who couldn’t speak English. It opened up a world for her, she says, adding that it gave her more time to read and gave her confidence to apply to the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. She was accepted and will enroll this fall.

Such stories, of course, are not new. This country was built on the backs of immigrants like Ana’s parents, many disoriented just like Consuelo Andrade, but forging ahead so that their children can have better lives. In California’s Central Valley writers like Steinbeck and Saroyan celebrated the field hands — their dreams and modest ambitions.

It struck me later that I had seen this same simultaneous fastidiousness and acceptance with the Andrades as I had the day before when I left Samuel Castro. They all have, as Dave Herb had told me, been too busy the last decades working themselves to the bone to pay attention to the bureaucratic definitions of their lives.

(This reporting was made possible by a grant from the Marguerite Casey Foundation’s Journalism Fellowship. The foundation “exists to help low-income families strengthen their voice and mobilize their communities in order to achieve a more just and equitable society for all.” For more information about their work, click here.)