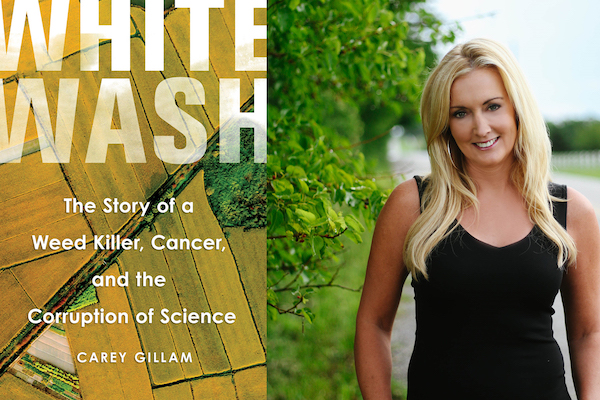

Editor’s Note: In the following interview, for Acres U.S.A., Tracy Frisch interviews Carey Gillam about her first book: Whitewash: The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer, and the Corruption of Science. Gillam, a “Kansas-based journalist turned glyphosate geek” has been a reporter for over 25 years, 17 of which were spent with Reuters covering, among other topics, economic policy, corporate earnings and commodities trading. In that time, Gillam’s reporting specialized on corporate agribusiness and the agrichemical industry. The public health deceptions she’s since uncovered are numerous. Two years ago she became Research Director with U.S. Right to Know, a nonprofit consumer group that “pursues truth and transparency in America’s food industry.”

This interview has been edited for length, but a link to the full (and more in-depth) conversation can be found at the bottom of the post.

Tracy Frisch: What’s the origin of the chemical that became the world’s most widely-used weed killer?

Carey Gillam: In 1950, while looking for new pharmaceuticals, the Swiss chemist Henri Martin synthesized the chemical we call glyphosate. … But it took Monsanto and John Franz, a young Monsanto chemist, to unlock the weed-killing magic within glyphosate and bring it to market as the highly profitable product Roundup. Franz discovered that glyphosate killed plants in 1970 and went on to receive great acclaim for his finding. In 1974, Monsanto rolled out Roundup as a very safe and effective weed killer, and it was quickly embraced for a number of different uses.

In your book, Whitewash, you note that the glyphosate patent was going to expire around the time that the first Roundup Ready crop — soybeans — entered the market.

This was certainly no accident. The company had very good sales over the years. But Monsanto discussed with investors its expectation that the glyphosate sales volumes would soar with the rollout of its Roundup Ready crops in the 1990s. Roundup use did explode, and Monsanto had fabulous sales. Selling the seeds and the herbicide that went along with the seeds was a really smart business play. Farmers that I interviewed did love it. For many years after these genetically engineered crops came out, Roundup was like gold.

When did Roundup start being widely used right before harvest?

That suggestion for glyphosate use came up fairly early on. Oklahoma wheat farmers thought that this could be helpful to them. The idea was to spray Roundup directly on your crops shortly before harvest to help them dry out. The problem, of course, is that this practice leaves higher residues of glyphosate in the finished products.

Glyphosate went on the market in 1974. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, fraudulent practices were discovered at IBT and Craven, two major testing laboratories that conducted many of the toxicological studies for Monsanto and other pesticide companies.

Three IBT officials were convicted of trying to defraud the government by covering up their research data. Though the company now claims it was a victim of the IBT fraud, Monsanto certainly had connections to it. A Monsanto employee had gone to work for IBT, was there during the scandal, and was charged in connection with falsification of scientific results. And Monsanto helped in his defense in the court case.

Even today, people still don’t know in which cases the EPA accepted the data sets from testing conducted at those discredited labs rather than insisting that the tests be redone.

There are still concerns that regulators may consider some tests done by these labs to be valid, though Monsanto will say that they had them all redone. But at this point we have a bigger concern. We now know that for many of the studies that the EPA relies on, Monsanto has worked very hard to manipulate the findings and the way they’re assessed. For instance, the documents we have show that the company has engaged in ghostwriting research papers that appear to be authored by scientists working independently of Monsanto.

Can you give an example of how Monsanto has influenced the EPA’s interpretation of a glyphosate study?

The 1983 mouse study illustrates a troubling dynamic. You can see in documents how Monsanto talked about what they did with that study and other studies, as far as regulators were concerned. The study in question involved 400 mice. The EPA’s toxicology experts looked at the study and came to the obvious conclusion: “This stuff causes cancer.” In the study, the mice, other than the controls, were dosed with glyphosate and some got these rare tumors. Monsanto’s response was to say, “You’re just not looking at it right. These tumors aren’t really due to glyphosate.” At first the EPA toxicologists held firm and remained outspoken. “Monsanto’s argument is unacceptable. Glyphosate is suspect. Our job is to protect the public, not the registrant.” They wrote words like these in memo after memo. Monsanto then hired a pathologist who, they said in their internal email chain, would convince the EPA that they were wrong. Lo and behold, he told EPA that there was a tumor in the control group that nobody had noticed before. The EPA toxicologists continued to fight back. This went on and on. The EPA had a separate outside group look at it, which told the agency to have Monsanto redo the tests. Monsanto refused. A decade later, in 1993, the EPA finally relented. They accepted Monsanto’s study and conclusions and classified glyphosate as having no evidence of carcinogenicity. Some of the EPA scientists refused to sign off on that determination. This case shows how hard it has been for the EPA to stick with the findings of their own scientists. This has occurred repeatedly for Monsanto, with PCBs and dioxin. Companies like Monsanto have a lot of clout, and they use that power. Monsanto spends a lot of money on lobbyists and campaign contributions, and political appointees hold the top positions at the EPA.

We seem to be at a watershed moment right now. From the outside it looks like this started when the International Agency on Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen. What do we know about how scientists make such assessments for IARC?

The International Agency on Research on Cancer is a unit of the World Health Organization that looks at different substances to determine their cancer hazard. As with the working group on glyphosate, the people that serve on IARC panels are independent scientists invited to participate. They work at academic universities and government agencies around the world and are not supposed to have any ties to industry or organizations. The World Health Organization does not employ them and they are not paid.

How is IARC’s work different than what the EPA does?

IARC looks at the best, most authoritative studies — only published, peer-reviewed research — whereas the EPA relies pretty heavily on studies and research presented by the companies themselves. A lot of those studies have not been published or peer reviewed. That’s a very big distinction.

I’m under the impression that the studies that chemical companies submit to the EPA are often confidential, so that independent scientists never get a chance to see it.

Yes. I’ve gotten copies of them myself, and every single page is stamped “Trade Secret. Confidential.” That is a problem. Over time, independent researchers and scientists have done a number of studies on glyphosate and Roundup, and they have found problems. And some of that is what IARC looked at and how they came to their conclusion.

The revelations coming out of Monsanto’s internal documents are breathtaking. Why are they being released?

These documents that I used for my book and that continue to churn out come from several sources. There are discovery documents coming out as a result of litigation against Monsanto. In them you see Monsanto’s internal conversations among themselves or with others in the industry. We’ve gotten documents through Freedom of Information from the EPA, the FDA, and other agencies. There are also state record requests, which we’ve gotten from state universities, that show various professors and other academics collaborating with Monsanto on certain issues — like Monsanto assigning them policy papers to write and drafting reports that would carry the names of these professors, though in reality Monsanto wrote them. Putting all these documents together gives a fairly complete picture of the deception that’s gone on for so long.

Do you think that IARC’s classification of glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen is what opened the floodgates to all the lawsuits against Monsanto?

It really is. The lawyers were aware of the research tying glyphosate and Roundup to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. But when IARC made its classification, it really did open the floodgates, and the lawsuits started piling on from people all over the United States who either have non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or family members who have already died from it. These are farmers and farm workers and others who were routinely exposed to glyphosate. Many of these farmers say they chose to use glyphosate because they had been led to believe it was so much safer than other herbicides.

As you have alluded to, one of Monsanto’s tactics to hide glyphosate’s health problems has been to work with academics as their paid operatives. Could you describe the behavior of one or two such scientists and their relationship to Monsanto?

There are academics all over the United States, Canada and Europe. Where Monsanto has forged collaborations or alliances to enlist these professors, they appear to be independent and neutral. Monsanto wants to leverage that to their benefit, and they talk about it. They have different ways of funding these academics, sometimes through grants or donations to their research programs or to their universities, or they may pay them as consultants. Bruce Chassy, for instance, was at the University of Illinois. Monsanto gave quite a bit of money to his program, funneled through the foundation there. They talk with Bruce Chassy about sending the money and about how much money. At the same time they’re communicating about things that Bruce Chassy can do that would be beneficial to their agenda. They have him traveling around the world, making presentations to policymakers in other countries about how wonderful and safe Monsanto’s products are.

Is he the one who was going to China without knowing what he’d be doing there?

Exactly. He was telling Monsanto, “I’m ready to go, but you haven’t told me what my mission is yet.” Monsanto was preparing slides and presentations and editing things for him. Their part in his appearances and articles was not disclosed, and that’s not what people expect when they think that they’re hearing from an esteemed, independent academic. It really made my jaw drop to read the emails where Monsanto wanted to set up a nonprofit organization to be used to promote its products and its agenda while attacking and discrediting scientists, journalists and other individuals who challenged the industry. They have set up a number of websites and nonprofits designed to look independent while they manipulate and influence media, public opinion, and, of course, lawmakers and regulators.

One notable example is Academics Review, a site that publishes pro-industry propaganda and attacks people who question the industry spin. In an email we’ve obtained that I talk about in my book, a Monsanto executive says, “From my perspective, the problem is one of expert engagement, and that could be solved by paying experts to provide responses. The key will be keeping Monsanto in the background so as not to harm the credibility of the information.” That’s so deceptive and unfair to people like farmers who just want the truth so they can make informed decisions. They deserve truth and transparency. I find such a concerted effort to deceive the public egregious.

The Séralini affair is another example of Monsanto tactics. What was unusual about the Séralini study?

The Séralini study was a two-year feeding study of rats that has become one of the most controversial of all the studies out there examining impacts of glyphosate and Roundup. It was published in 2012 in Food and Chemical Toxicology, but after a storm of protests engineered by Monsanto it was retracted and then republished in another journal. The study found health problems in rats fed genetically modified corn or given Roundup herbicide. The study ran much longer than most, and Séralini’s team said its work showed much deeper investigation was needed into the safety of GMO foods and of Roundup. Monsanto went after Séralini pretty hard with a variety of tactics. They got many different individuals to write letters of complaint and demand the journal retract the Séralini study. The documents show that Monsanto had a financial relationship both with the editor of the journal that ultimately retracted the study and with a scientist on the editorial board. The documents show that even though the company orchestrated the demand for a retraction, they wanted it to appear to be independent of the company’s influence.

Where do we find glyphosate in the environment?

It has been found in our rivers and streams, and in municipal drinking water supplies. These are the findings of government scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey — not some random, crazy scientists!

What about in soil? In terms of growing plants, isn’t that of great significance?

The soil is something that really concerns me. The presence of glyphosate affects the health and nutritional value of our food. A number of scientists have documented changes in the soil after multiple years of glyphosate use. They’ve shown that heavy glyphosate use, which is so common, affects soil properties, plant growth, and soil microorganisms. Over time, the health of soil microbial community is eroded, and the soil becomes almost sterile.

Is it true that glyphosate has a patent as an antimicrobial or antibiotic?

Scientists are seeing that with repeated applications of glyphosate the soil becomes bereft of its natural microbial community, which negatively impacts the crops that farmers are using glyphosate to protect. Plants lose access to the nutrients mediated by these soil organisms and become more vulnerable to disease. So then farmers use more fungicides and more fertilizer. Glyphosate is creating an environment that encourages more pesticide use and we are eating food with more pesticide residues. Our government has even documented this. In its latest report, 85 percent of the foods that the USDA tested showed pesticide residues, the highest level in more than a decade.

In Whitewash, you write about the failure of government agencies to test food for glyphosate residues, despite the existence of monitoring programs for many types of pesticides. How did they manage to avoid testing for glyphosate?

A number of years ago this became a pet peeve of mine. Every year the USDA and the FDA monitor food for pesticide residues. They’re required to do this testing and keep track of it in a database. This allows government agencies to determine if food producers are violating the allowable levels determined by the EPA for particular pesticides. The monitoring program also enables us to understand what we’re taking into our bodies. As I’ve stressed, glyphosate is the most widely used herbicide in history, but it’s the only pesticide that neither the USDA nor the FDA have tested for. (The USDA did one special project in 2011 looking at glyphosate residues in soybeans and found residues of the weed killer in more than 90 percent of the samples.) For decades they have refused to test for it. Many years ago I started asking them why they didn’t test for glyphosate. They told me that, first, it’s so safe so it doesn’t matter if they test for it. Second, they would say that it’s really expensive to test for. The third reason was, “We know that if it’s in the food, it’s probably not in very high amounts.” I found that laughable.

Don’t they require the pesticide manufacturer to provide a laboratory method for testing as part of its registration?

Wouldn’t that be a good idea? Actually, I don’t know. I think the companies do give a method, but that doesn’t mean the government agencies have the equipment to test for it. What they’ve told me is that doing the test is very expensive, and the methodology is very complicated. Interestingly, we know from internal documents that in 2017 the USDA was slated to start testing for glyphosate. They laid out what they were going to test. I was writing the story. Then early last year, shortly before they were supposed to start this program, they decided that they were going to continue to not test for glyphosate. The FDA has an even more interesting little saga. In early 2016, they said they were going to start some limited testing for glyphosate residues. I reported that in a big story that was picked up all over the place. The FDA was not happy that I reported that because they didn’t want people to know. That surprised me. If you’re a government agency and part of your job is to test food for pesticide residues, why wouldn’t you want to shout it from the rooftops when you’re finally going to start testing for the most widely used herbicide? You’d think they would be proud of it, but they weren’t.

Internal documents show that they did start testing and found residues that I suppose they didn’t anticipate, like glyphosate contamination in honey and oatmeal. One of the FDA chemists found pretty high levels of glyphosate in honey, even in the organic honey, which created quite an uproar. Bees are getting it from their environment, which is doused with glyphosate. In addition to farm fields, the herbicide is used on golf courses, parks, yards, playgrounds, roadsides, and other settings. Lawsuits have been filed against honey producers because of glyphosate being found. Yet EPA and FDA are remaining mum on this. After I reported on the oatmeal and the honey issues, the FDA glyphosate testing program was suspended. It was supposed to have resumed in 2017, but we haven’t heard anything. I recently received word that the FDA has explicitly told its scientists not to test any honey for glyphosate in 2018.

On top of that, didn’t the federal government bump the maximum residue level for glyphosate up many times higher than it used to be?

Yes. Over the years, the legal limits for residues of glyphosate have been raised many times, for many different foods and feed crops.

I loved that those members of the European Parliament did a urine test. What a great way to publicize glyphosate’s ubiquitousness!

When you have your own bodily fluid tested and you find that you have this pesticide in you, it really does resonate more. I’ve had my urine tested, and though I was on the very low side of the average among people tested at this particular laboratory, it still impacts you. You also realize that this is not the only pesticide you’re carrying around inside your body.

You reported that the average Member of Parliament had a 17 times greater concentration of glyphosate in their urine than the European drinking water standard.

Yes. That woke some people up a bit. With the license for glyphosate expiring in December, the European Union has been caught up in hot debate over whether to renew it. Parliament voted in October to ban glyphosate, but the member states have been struggling to reach a qualified majority on the re-authorization issue. It’s a very deeply divided situation. At the same time, the EPA is due to issue a new risk assessment of glyphosate.

Is the glyphosate saga indicative of the failure of mainstream chemical agriculture?

I say that Monsanto and glyphosate represent a poster child for a much larger problem — the pesticide treadmill. We’re stuck in a place of dependency, thinking that we can only grow food, manicure our lawns, and take care of our golf courses with an array of pesticides. It’s not good for our health or the environment, or for our future or that of our children.

I’m glad you included discussion of some front-line populations in your book. Why is glyphosate so widely used in Hawaii?

Hawaii has become a testing ground for Monsanto and other large seed companies. It offers an ideal year-round growing environment with its temperate climate, good rains, and sunshine. Some people call it a poison paradise. Big agrochemical and biotech companies have leased or purchased land there to test and grow their genetically engineered seeds. Glyphosate is one of the pesticides that they’ve been using, as well as a host of restricted-use pesticides. People there are very concerned that these pesticides are contributing to health problems.

What kinds of things are the citizens pushing for?

They’re scared and are trying to figure out what they can do to protect themselves. One of the main things they’ve asked for was transparency. Tell us what you’re spraying, how much you’re spraying, and when you’re spraying. The companies have even fought back on providing that information. People have also demanded increased buffer zones so there’s more distance between them and the pesticide spraying. Studies have found the pesticides in the water, soil, and dust, and the residue is in people’s homes and schools. It’s pervasive.

You wrote that weed scientists and others knew that the agricultural system Monsanto was promoting would be a perfect incubator for resistance, but neither Monsanto nor the EPA or USDA would listen to them. Where are we now?

It’s too late. I was reminded of how early people sounded the alarm bells on this problem. The weed scientists, who were in the best position to know, warned everybody, shortly after genetically engineered crops were introduced. They predicted that such extensive, repeated use of one chemical would create populations of resistant weeds and the herbicide wouldn’t be effective anymore. Monsanto brushed them off and convinced the EPA to ignore them, too. I remember talking to Monsanto about weed resistance issues and them telling me it wasn’t going to happen. Only after facts on the ground shifted and the company and the regulators could no longer deny the epidemic of resistant weeds did they get engaged. By that time, 2011 or 2012, the horse was already out of the barn. Farmers were using two and three times more glyphosate to try to kill these weeds. A lot of cotton farmers had to hire people to pull weeds by hand. It’s been extraordinarily costly in labor and decreased production.

Sounds like the worst of all worlds.

The chemical industry’s answer has been to pile on more chemicals. They’ve created crops with tolerance to both dicamba and glyphosate and to 2,4-D and glyphosate. This pesticide treadmill serves the chemical industry really well, but doesn’t benefit public or environmental health. Dicamba and 2,4-D have their own range of toxic problems. Dicamba especially is notorious for not staying where you put it. It volatilizes and drifts. It’s killing other farmers’ crops around the Midwest and South. Farmers who don’t have these specialty dicamba-tolerant seeds are finding their crops damaged or destroyed. It’s extremely costly. Farmers are suing and there are regulatory battles. It didn’t have to be this way at all.

Is there anything else you want to say about your book?

I hope that people understand that my book Whitewash is not aimed at Monsanto or at one particular chemical. I tried rather to use glyphosate and Monsanto as the storytelling vehicle to illuminate a much larger problem — our complacency with a pesticide-dependent system. It’s creating an unhealthy future for our children, which sets them up for a range of diseases, and it’s destructive to ecosystems. We’re smarter than this. The information is out there. We just need to pay attention to it. The book aims to help wake people up to that.

(“Glyphosate: A Toxic Legacy” was originally published in the January 2018 issue of Acres U.S.A. and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from Tracy Frisch. To view the interview in its entirety, please click here. For more information about Carey Gillam and her book, visit her website.)