Small Towns in New York and Vermont Share a Water Contamination Crisis, But Not an Official Response

Tracy Frisch

It was around Halloween in 2015 when Michelle O’Leary moved north from Columbia County, N.Y., to a Hoosick Falls fixer-upper with her husband and two children.

Before the family bought their first home here, O’Leary says, she investigated everything from the local school system to crime rates, the sex offender registry and local weather statistics. She even learned that Hoosick Falls’ drinking water had been rated as the best in Rensselaer County in 1984.

But two weeks after the family settled into their new home, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared that the Hoosick Falls tap water was unsafe to drink because of contamination with perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA — an industrial chemical that has been implicated in cancer, developmental problems and endocrine disruption.

“My happiness was ripped out from under me,” says O’Leary.

She and her husband had unknowingly chosen a house “smack dab” in the middle of several toxic sites, including two Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics factories and a shuttered Honeywell plant, all of which used PFOA for decades before production of the chemical was phased out a few years ago.

In late July, the EPA officially added the Hoosick Falls Saint-Gobain plant to the federal Superfund list. The designation allows federal resources to be directed toward a cleanup effort, although the scope and timetable of that effort remain to be determined. State officials say a filter system installed last year to remove PFOA has made the village water safe to drink again. But the groundwater that supplies the Hoosick Falls water system, which serves 4,000 customers, remains heavily contaminated with PFOA as well as vinyl chloride and dichloroethylene. For now, many people in Hoosick Falls still choose to drink bottled water, though free supplies of it ended on September 1.

One idea under discussion is connecting Hoosick Falls to the Tomhannock Reservoir in Pittstown, which supplies drinking water to the nearby city of Troy. But there is no firm plan yet for how to finance or carry out such a project.

Meanwhile, just across the state line in North Bennington, VT., officials announced last month that Saint-Gobain has agreed to fund a $20 million project to extend municipal water lines to about 200 homes where private wells were contaminated with PFOA. The contamination, from a factory Saint-Gobain closed about 15 years ago, was discovered a few months after PFOA first made headlines in Hoosick Falls. In North Bennington, Saint-Gobain has provided point-of-entry filters for homeowners with tainted wells. But the filters require periodic replacement and maintenance, and the state did not accept them as a long-term solution.

The differences in the way New York and Vermont have responded to PFOA contamination in the two neighboring communities are numerous. And in Hoosick Falls, some have taken note that North Bennington seems to be moving more rapidly toward a long-term remedy for PFOA contamination.

“They found out after us — and then surpassed us in every way,” says O’Leary.

When Michelle O’Leary learned Hoosick Falls’ tap water was contaminated, she established a group of volunteers to spread the word and distribute bottled water. (Image: Joan K. Lentini / Hill Country Observer)

Sounding the alarm

The presence of PFOA contamination in Hoosick Falls’ water was first revealed in the summer of 2014, when a former village trustee, Michael Hickey, commissioned his own tests of local tap water. Hickey had gone searching for answers after several people he knew died from unusual types of cancer, including his father, who had worked at one of the local Saint-Gobain plants.

PFOA was not among the contaminants for which the village was required to test, so no one had looked for it. In 2009, the EPA had set an advisory limit of 400 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA in drinking water. The test of Hickey’s own tap water showed a concentration of 540 ppt. Subsequent state tests showed levels in excess of 600 ppt at several collection points. Hickey and a local doctor soon brought the test results to the attention of local officials. But for more than a year after that, the village and state continued to insist that the water was safe to drink.

By the fall of 2015, the EPA was aware of the situation, and officials at the federal agency argued that Hoosick Falls residents needed to be told they were drinking water with dangerous concentrations of PFOA. But Politico later reported, based on documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, that state health officials “resisted sounding a public alarm” — and actively disputed the EPA’s contention that the water was unsafe.

Eventually the EPA went forward on its own to announce that the water shouldn’t be used — for drinking, cooking or even running a humidifier. Even after that, the state Health Department issued a “fact sheet” saying that “normal use” of the water was safe, though the agency soon reversed itself and backed the EPA’s stance.

To read the EPA’s full 2016 report on the adverse health affects of PFOAs, click here. (Image: epa.gov)

‘Water angels’ step up

To replace village water, Hoosick Falls residents were told they could pick up free bottled water at the local supermarket.

O’Leary, who in the past had received public assistance as a single mom caring for a son with special needs, says she worried about the many people who wouldn’t be able to lug home gallons of water — the elderly, disabled, sick and those without cars. Since no one else was offering to do so, she decided to take on the job of delivering water to anyone who couldn’t get it.

With the town abuzz via social media and people turning out at community meetings, O’Leary was able to enlist volunteers for her project. The Water Angels, as they called themselves, wore little badges with their names and began making water deliveries in December 2015. Mostly they were met with gratitude, but they also had detractors. Some people, O’Leary says, didn’t want to be reminded of the pollution in their community and seemed suspicious or hostile to those pushing for more information and speedier solutions. Her newcomer status didn’t help matters.

At least once, O’Leary says she delivered 1,100 gallons of water in a single day. She fielded calls from morning till night. Many people had questions, and the Water Angels carried around pamphlets and other literature. O’Leary says people who didn’t read the news and weren’t on social media were often in the dark. In February 2016, three months after the EPA issued its water advisory, volunteers in her group encountered an 85-year-old man in a third-floor apartment who wasn’t aware that he shouldn’t be drinking the village tap water. She wanted to spread information about the water crisis by going door to door in the village and leaving flyers on car windshields, but says village authorities strongly discouraged her from doing so.

Toward the end of March 2016, O’Leary says, David Borge, the village mayor at the time, sent an e-mail to thank her for her service — and told her that he was putting her project under the village’s jurisdiction and assigning it to someone else. The Water Angels had been a private, voluntary effort, and the village wanted the group to provide a list of those receiving water deliveries.

O’Leary says some people distrusted the village government so deeply that they opted to stop getting deliveries of bottled water rather than share their information with the village. A few months later, the village began asking people for proof that they were unable to pick up the water jugs themselves. Class-action lawsuits against Saint-Gobain were in the works, but the village and the company, which has about 200 local workers and remains Hoosick Falls’ largest employer, were in close communication.

“A lot of people are afraid of repercussions,” says O’Leary.

Proactive in Vermont

PFOA is sometimes called C-8, for its chain of eight carbon atoms, each bonded to fluorine. The carbon-fluorine bond is extremely strong, making PFOA virtually indestructible. So it stays in the environment essentially forever: It doesn’t degrade in water or soil, and plants and animals don’t metabolize it.

First manufactured in 1947, PFOA is best known for its role in making Teflon, but it’s also been a mainstay in the industrial production of many consumer products, from water-repellent outdoor clothing and gear to stain-resistant carpet and upholstery, as well as floor wax, carpet-cleaning liquids and some paints.

So when PFOA contamination in Hoosick Falls became big news at the end of 2015, some people in North Bennington began asking questions. Saint-Gobain had run a plant there that used PFOA.

At the former Chem-Fab plant, which Saint-Gobain acquired in 2000, workers dipped fabric in vats containing PFOA to weatherproof it for architectural applications. Chem-Fab employed this process for end users like the Denver airport and the Georgia Dome in Atlanta. Two years after it took over, Saint-Gobain shut the North Bennington plant, shifting production to a facility in Merrimack, N.H. (Last year, PFOA contamination was found in Merrimack’s public water supply, which serves 25,000 people.)

April 2016 — state officials unload boxes of bottled water for residents living near Saint-Gobain’s plant in Merrimack, N.H. (Image: Jim Cole / Vermont Public Radio)

But when some North Bennington residents asked the state to look into the possibility of PFOA contamination near the defunct plant, the response was far different from what Hoosick Falls residents had encountered in their state.

Sylvia Broude, executive director of the Toxics Action Center, a New England-wide environmental organization that works with communities affected by pollution, says Vermont took a much more pro-active approach. “The state of Vermont tested the same day it heard about contamination,” she says.

The results showed the local municipal water system, which has its source miles away from the former Chem-Fab plant, was fine. But the drinking water wells of at least 200 homeowners outside the system’s service area were contaminated with PFOA. One groundwater sample taken near the defunct plant turned up PFOA at a concentration of 2,000 ppt.

Rapid response

Alyssa Schuren, who served as Vermont’s environmental conservation commissioner under then-Gov. Peter Shumlin (D), described at a conference in Boston recently how the state jumped into action after finding PFOA in North Bennington.

Schuren said a staffer burst into her office with the initial test results from North Bennington on a cold day in February. Five of the six water samples collected in an initial round of testing had PFOA levels the state deemed unsafe. The next day, state officials and the EPA addressed the gravity of the situation at a packed community meeting. Fifteen media organizations showed up to cover the session. The state immediately offered free bottled water to homeowners. And within about a week, a state contractor was making door-to-door water deliveries to 500 households.

Richard Spiese, a hazardous site manager and environmental analyst at the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, said in phone interview last month that by being proactive, the state was able to sample nearly 85 percent of the private wells in the targeted area during the first couple weeks after the contamination was discovered.

Rather than waiting for homeowners to come forward to have their water tested, teams of Vermont DEC staff systematically knocked on doors within a 1.5-mile radius of the former Chem-Fab plant. They made evening rounds to talk with people who weren’t home during the day. And that wasn’t the only occasion when they went door-to-door.

“When we got the first water results late on a Friday, we stuffed the envelopes and hand delivered them on Saturday,” says Spiese.

In the first two or three months after PFOA was detected, Spiese says he spent three days a week in North Bennington, staying overnight at a motel.

Spiese’s depth of involvement in the situation made an impression on Shaina Kasper, the state director for the Toxics Action Center. She described how once, when Spiese went out to eat in Bennington, people in the restaurant gave him a standing ovation.

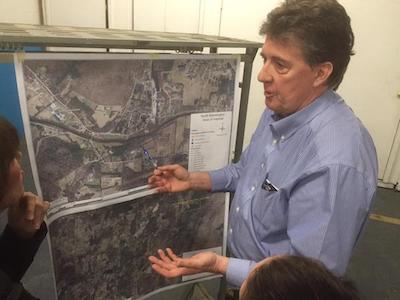

Richard Spiese, project manager for Vermont’s Wastewater Management Program, talks with North Bennington residents about polluted wells. (Image: Vermont Public Radio)

In search of answers

After they stopped delivering water in Hoosick Falls, the Water Angels changed their focus and renamed themselves NY Water Project. O’Leary and other members of the group have continued to demand answers and action about toxics and the local water situation.

Before her family moved to town and found themselves in the middle of an environmental crisis, O’Leary says she had never thought of herself as an activist. “I kept to myself,” she says. “I never thought I’d be talking to crowds or speaking on video or to reporters.” Although it has often led to frustration, she says she has no regrets about taking on the challenge. She says, “I think the only reason anything has been accomplished is because of people speaking up.” She and others have been disheartened, though, by how the New York governor, state agencies and Legislature have responded to the local water crisis.

“There have been numerous times that New York State has had an opportunity to do right by Hoosick Falls residents,” says O’Leary. Instead, she maintains, state officials repeatedly withheld important information, played down the problem and failed to provide answers to citizens’ questions. Throughout the first half of 2016, for example, local activists called for legislative hearings into how state health and environmental officials responded to the initial discovery of PFOA — and why it took more than a year to tell the public that the village water contained unsafe levels of the chemical. After a series of shifting explanations from state legislators as to why such a hearing couldn’t be arranged, the state Senate finally staged a daylong hearing in Hoosick Falls last August.

More recently, Republican leaders in the state Senate have balked at releasing a potential source of information about the extent of local contamination with PFOA and other compounds. Last September, the Senate Health Committee subpoenaed records from Saint-Gobain, Honeywell and Taconic Plastics, whose plant in the neighboring town of Petersburgh, N.Y., contaminated water supplies there. The records purportedly detail the companies’ use and disposal of PFOA and other perfluorinated compounds — as well as the results of contamination tests on the companies’ properties. But the committee chairman, Long Island Republican Sen. Kemp Hannon, has steadfastly refused to release the documents to the public.

In an interview earlier this year on Albany-area television station WRGB-Channel 6, Hannon responded to the criticism this way: “The people who have legitimate interest in those documents have been offered them. Period.” But State Sen. Brad Hoylman (D), the ranking Democrat on the committee, has repeatedly called for the release of the documents, arguing that village residents whose life and health are at stake deserve to see them. He says the chairman has responded by saying the documents are confidential.

In addition to the contamination already documented at current and former manufacturing sites in Hoosick Falls, PFOA also has turned up in high concentrations in a capped landfill near the Hoosic River, which runs through the village.

Downtown Hoosick Falls as seen from across the Hoosic River. (Image: Joan K. Lentini / Hill Country Observer)

Blaming the EPA

At last August’s state Senate hearing in Hoosick Falls, New York’s health and environmental conservation commissioners testified at length but expressed no regrets about how their agencies had handled the Hoosick Falls water situation. Instead, they blamed their initial misleading messages about the safety of the village’s water on what they claimed was confusing guidance from the EPA.

But the EPA’s stance on PFOA hadn’t changed during the period in question. Beginning in 2009, the EPA set an advisory limit for short-term exposure of 400 ppt for PFOA in drinking water. The initial tests of Hoosick Falls water clearly exceeded that level.

The EPA did subsequently lower its advisory limit for short-term exposure to 100 ppt in drinking water, and in June 2016, the agency established a still lower limit of 70 ppt for long-term exposure to PFOA. All of these limits are advisory; the agency still has no legally enforceable limit for PFOA in drinking water. In 2013, the EPA listed PFOA, PFOS and four related compounds under its Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule, which effectively required large public water systems to test for these chemicals. Based on the results of this testing, EPA has estimated that drinking water supplies serving 6 million people nationally are contaminated with one or more of these compounds. But small water systems that serve fewer than 10,000 users, like the one in Hoosick Falls, have been exempt from the testing requirement.

The result is a big data gap. Critics point out that 90 million people rely on small water systems or private wells that are exempt from testing. Some also question the adequacy of testing methods, given that scientists have linked PFOA to health effects at concentrations as low as 1 ppt. That concentration is equivalent to one teaspoon in the water of 1,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

NY Water Project helped to push for passage of a new state law covering “emerging contaminants” such as PFOA. The new law requires all public water systems in New York, even small ones, to test for previously unrecognized contaminants that the state identifies. That means small water systems serving 2.5 million New Yorkers will now be subject to testing, and the new law provides some funding to help smaller systems pay for these tests.

The state’s new testing requirements were included in the Clean Water Infrastructure Act of 2017. Championed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D), the legislation allocated $2 billion for upgrading public drinking water systems. Some of these funds theoretically could be tapped to help Hoosick Falls connect to an alternative water supply.

Strict standard

After PFOA was detected in North Bennington, V.T. issued an emergency rule setting its groundwater limit for PFOA at 20 ppt. That’s far lower than the current federal level of 70 ppt for drinking water — and unlike the federal guideline, it’s an enforcement standard that’s not just for drinking water.

State toxicologist Sarah Vose said last month that she could not answer questions about the details behind Vermont’s strict limit, because Saint-Gobain was contesting the standard in a pending legal action. The company dropped that lawsuit later in July.

But Kasper, of the Toxics Action Center, says the Vermont PFOA limit is the result of a process the state applies to all toxic chemicals. “The 20 ppt limit came about using the same comprehensive formula the state uses across the board, taking into account the research and the most vulnerable populations, such as children and infants,” says Kasper. Because of “how quickly the state was responding” in the North Bennington PFOA crisis, she says her group didn’t fill its customary role of community organizing, outreach, technical assistance and media work. Instead, the group tried to do things the state was unable to do.

Within weeks of PFOA being detected, Kasper says private lawyers began aggressively soliciting North Bennington residents, offering to file legal claims on their behalf. In response, Kasper’s group worked with the Vermont Law School to help local people weigh the legal issues and make good decisions about legal representation. Together they developed a list of questions for people to use, for example, in interviewing prospective lawyers.

Kasper’s organization also pushed for state legislation approved this year to allow the state to start construction on extending municipal water lines when private wells are contaminated — rather than having to wait for the state to recoup costs from the party deemed responsible for the pollution.

But the Toxic Action Center’s biggest legislative goal — to require industries to disclose all chemicals they use, not just those regulated as hazardous — remains unfulfilled.

Blood tests track exposure

Just about all Americans have PFOA in their bloodstreams. The national average load is 2 parts per billion. Blood tests conducted by New York and Vermont for Hoosick Falls and North Bennington, respectively, found many people with far higher concentrations in their bodies.

In Hoosick Falls, where 2,081 people were tested between February and April last year, the geometric mean for those tested was 23.5 ppb, 12 times higher than the national background level. People with the highest levels of PFOA had more than 400 ppb in their blood. In Bennington County, the 477 residents tested between April and June 2016 had an average of 10 ppb of PFOA in their blood, with one resident testing at 1,100 ppb.

Although PFOA blood levels cannot predict a person’s exact health risks, they do suggest the magnitude of exposure. Ongoing exposure to PFOA in drinking water increases the concentration of the chemical in the blood. If the source of exposure is removed, such as when an effective water filtration system is installed or a new clean water source goes online, blood levels will gradually drop over a matter of years.

Humans and other animals are incapable of metabolizing PFOA or otherwise breaking down the molecule, which is not found in nature. Although the chemical is slowly excreted through the digestive tract and kidneys, much of it gets repeatedly reabsorbed into the bloodstream. Individual rates of excretion vary widely, perhaps due to differences in kidney function and in the gut microbiome.

Tracking contamination

Schuren, the former Vermont environmental conservation commissioner, says addressing the crisis in North Bennington was only the first step in the state’s efforts to deal with PFOA and related compounds. She discussed the case in June at a conference on highly fluorinated compounds. The conference, held at Northeastern University in Boston, featured top research scientists as well as government officials, lawyers, journalists, environmentalists and people from communities affected by contamination.

Schuren described how, after dealing with the immediate issues in North Bennington, the Vermont DEC tried to determine where else highly fluorinated compounds had been used or disposed of. The agency sampled additional sites around the state. She said PFOA and related chemicals are used in such varied applications as wire coating, semi-conductors, tanneries and firefighting foam against fuel fires, and they end up in landfills and wastewater treatment plants.

Locally, the state’s investigation revealed PFOA in the municipal water supply in Pownal, which serves 400 customers. As a short-term remedy, the Pownal system has been provided with a granulated activated charcoal filter; the state says its long-term goal is to obtain clean replacement source for the town.

New York also has attempted to find other sites where public drinking water supplies had become contaminated. A state water quality “rapid response” team conducted targeted sampling of 38 regulated public drinking water supplies within a half-mile of facilities that reported having used either PFOA or the related compound PFOS, a major ingredient in firefighting foam. The state said it didn’t find either substance in the majority of water supplies tested. And where these compounds were detected, the state said levels were below the EPA’s lifetime guideline of 70 ppt.

In March, the New York DEC announced that the CTI Agri-Cycle composting facility in the rural Buskirk area of the town of Cambridge had tested positive for six perfluorinated compounds, including PFOA and PFOS, in paper mill sludge, finished compost, a monitoring well and a stormwater collection pond. Some residential wells near the facility also tested positive for PFOA and PFOS, though concentrations were below the EPA’s 70 ppt advisory limit. After discovering the contamination at CTI, the state expanded its investigation to six recycled paper mills and six other facilities that use recycled paper sludge in manufacturing.

For a number of years, Agri-Cycle has received tipping fees from paper mills for accepting their sludge. A decade ago, the composter did not sell its compost. Instead, it then spread it thickly on farmland at the site of its composting facility, some of which was in pasture grazed by a herd of cattle. Schuren says laws regulating PFOA and related chemicals aren’t strong enough, but that budget constraints make it hard for government to fulfill the promise of legislation that expands environmental protection.

Although the EPA sets a floor for regulation, states should do more, she says. And when it comes to regulating toxic chemicals, Schuren favors taking a precautionary approach — rather than waiting for a finding of absolute certainty that a substance poses a significant hazard.

In the case of North Bennington, says Schuren, “I feel great about our response, but I don’t think it’s enough.”

(“Two states, two paths: Border makes for sharp contrasts in handling of tainted-water crisis” was originally published by the Hill Country Observer and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the author.)