Activists to Congress: This New GMO Labeling Law “Doesn’t Pass the Laugh Test”

Tracy Frisch

This was supposed to be the watershed moment for activists around the region who had long campaigned for labeling of genetically modified foods.

On July 1, Vermont became the first state in the nation to require labels on food products with genetically engineered ingredients. The state’s law, which the Legislature passed by an overwhelming margin in 2014, was the result of years of effort by grassroots activists who spoke out forcefully and jammed public hearings to demand the right to know what was in their food.

As Vermont’s law staved off a court challenge and moved toward implementation this summer, activists in New York and Massachusetts gained a new burst of momentum in their effort to pass similar labeling laws in those states.

And as the effective date of Vermont’s law neared, a series of large food companies announced that, rather than create separate labels for one small state, they would simply start nationwide labeling of products with genetically modified ingredients. A few companies also made plans to reformulate their products to omit these ingredients.

But in mid-July, Congress rode to the aid of processed food, pesticide and biotechnology companies, which had bitterly fought Vermont’s labeling law. With no hearings and little debate, first the Senate and then the House passed a much weaker federal law for disclosing genetically modified ingredients in food — and barred states, including Vermont, from setting their own labeling requirements. President Obama signed the federal measure into law on July 29.

Although the new federal law directs food companies to disclose whether products contain genetically modified ingredients, the companies won’t have to say so directly on product labels. Instead, the labels can simply include a QR code, Web address or toll-free number where consumers can seek information about genetically engineered ingredients. A consumer theoretically could find out about genetically modified ingredients by scanning the QR codes on packages while shopping, but only if the consumer has a smart phone with the appropriate app and can get adequate reception in a particular store.

Instead of written labels (which can be read without a smart phone) the new GMO law uses QR codes like this one. (Image: undark.org)

“The idea that this will provide right to know is ridiculous,” says Andrea Stander, the executive director of Rural Vermont, which pushed for Vermont’s labeling law. “It doesn’t pass the laugh test.”

Now Stander and other local advocates of labeling are trying to settle on a path forward, perhaps by challenging the new federal law in court — or, more likely, by organizing to push for tougher standards as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) embarks on a two-year process to craft rules for implementing the new federal law.

Widespread but secret?

Foods made from genetically engineered crops began appearing on supermarket shelves in the mid-1990s, and within a few years the vast majority of processed foods contained these ingredients. Today, about 90 percent of the corn, soybeans, sugar beets, canola and cotton grown in the United States is genetically engineered.

Unlike plants developed through traditional breeding practices, most of the genetically engineered varieties sold commercially so far contain foreign genes extracted from animals, bacteria or unrelated plant species. Critics say this makes the altered crops fundamentally different — and risky. The companies that produce engineered crops claim they are safe, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has supported those claims — relying heavily on industry data.

The United States stands nearly alone among industrialized nations in resisting consumers’ calls to label foods produced with genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, despite national surveys showing as many as 90 percent of Americans favor labeling. Until Vermont’s law passed two years ago, major agricultural, chemical and biotechnology companies like Monsanto and Dow had succeeded in thwarting all labeling legislation.

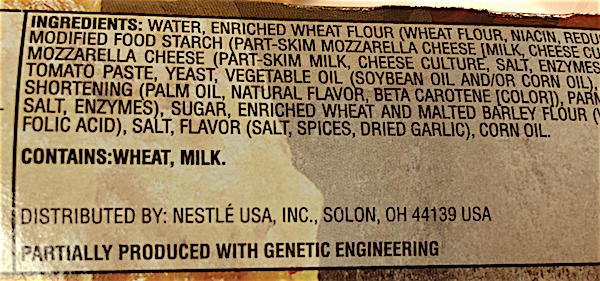

Vermont’s labeling law set a simple standard: It required food producers to put four to six words on packages of food containing genetically modified ingredients. Companies had a choice of three phrases: “Produced with genetic engineering,” “Partially produced with genetic engineering,” or “May be produced with genetic engineering.”

A picture of a frozen pizza box posted on social media with the caption: “My pizza is partially produced with genetic engineering.” (Photo: reddit.com)

In determining the percentage of genetically engineered ingredients that would require labeling, Vermont followed the 0.9 percent threshold set in Europe, where labeling laws are widespread. The Vermont law did not cover foods containing meat or poultry, such as many canned soups, because separate U.S. Department of Agriculture rules govern labeling for these products.

But the new federal law has now nullified all existing state laws that mandate GMO labeling, and it prevents states from requiring labeling in the future. Apart from Vermont, Maine and Connecticut had enacted laws requiring GMO food labeling once a certain number of other states mandated it. And in Alaska, where wild salmon are central to the fishing industry, the state had passed a law in 2005 requiring labeling of genetically engineered fish and fish products. (The FDA approved the first genetically engineered fish — a salmon — in November.)

In addition to blocking state food-labeling laws, the new federal law also pre-empts state laws that had required labeling of genetically modified seeds, thereby denying farmers and gardeners the right to know whether seeds were produced with genetic engineering. Vermont had had a seed-labeling law in place since 2004; Virginia also had such a law.

Stander calls the new federal law “a dramatic abrogation of states’ rights.”

Vermont’s seed-labeling law was working well, she says. In addition to Vermont’s many organic farmers, some conventional growers in the state also had chosen not to use genetically modified crops. The seed law, Stander says, had made it possible to track the number of acres of GMO crops in Vermont — a number that has increased dramatically in the past decade.

GMO labels take off

Because Vermont’s labeling law was in place for nearly a month before Congress overrode it, and because the state law carried substantial penalties for noncompliance, most if not all food producers that sell their wares in Vermont have been labeling foods containing genetically modified ingredients for much of this summer — and not just in Vermont.

As the July 1 effective date of Vermont’s law neared, major food companies like Campbell Soup Co., Mars Inc., PepsiCo, Nestle and General Mills started to label their products nationally. The wording required by Vermont’s law generally appears on food packages just below or near the federally mandated ingredients list — and was evident in a spot-check of a variety of packaged foods at an eastern New York supermarket in late August.

“They’re labeling, and the sky is not falling,” says Stacie Orell, the campaign coordinator for GMO Free NY, a group that has been pushing Albany to pass a labeling law for New York.

Orell says that to make her case to New York’s legislators, she had recently been carrying around a show-and-tell kit with sample product labels resulting from Vermont’s law — including products like Skittles candy (from Wrigley’s), an empty bag of chips from Frito-Lay (a PepsiCo subsidiary), a Campbell’s soup can and a package of M&M’s.

Campbell Soup was the first of these large companies to announce, in January, that it would begin labeling nationally. Others, such as PepsiCo, never made an official announcement, but Orell says people have seen GMO-containing products labeled on store shelves as far away from Vermont as Hawaii.

Whether these companies continue to label genetically modified products voluntarily under the new federal law remains to be seen.

Massachusetts and New York campaigns

Orell first became aware of the controversy surrounding GMOs in 2009 and began reading books like The World According to Monsanto. Around that time, she completed a master’s degree in environmental conservation from New York University and decided she wanted to engage the political system.

“The more I learned, the angrier I got,” says Orell.

In Albany, Orell helped to form a statewide coalition that has been pushing for a GMO labeling law since 2013. (The New York coalition includes GMO Free NY, the Northeast Organic Farming Association of New York, Food and Water Watch, Hunger Action, Consumers Union, the New York Public Interest Research Group, Natural Resources Defense Council, Catskill Mountainkeeper, Fire Dog Lake, Good Boy Organics, the Green Party of New York, the Brooklyn Food Coalition and the Sierra Club Atlantic Chapter.)

In past years, when she and other advocates met with legislators to advocate for GMO labeling, they “looked at you like you had two heads,” says Orell.

But as Vermont’s law neared implementation this year and companies actually started labeling, Orell says there was a sea change in the response to her efforts.

“The volume was turned up in Albany,” she says.

Coalition members actively pushed out alerts to call legislators and come to lobby days. Some 300 people came to the coalition’s March lobby day, staging a big rally on the Capitol staircase. In some districts, labeling proponents met individually with legislators — or held protests and rallies outside legislators’ offices.

Protesters assemble in March at the New York State Capitol in Albany to lobby legislators to make GMO labels on foods mandatory. (Photo: Erik McGregor / Pacific Press / Getty Images)

“We were able to get a majority of both houses of the legislature to sign on as sponsors of the labeling bill or promise to vote for it,” says Elizabeth Henderson, an organic farmer from western New York who worked with Orell on the campaign. “But we were not able to get the leadership to bring it up for a vote.”

Orell and Henderson say the New York labeling bill was strongly opposed by lobbyists for the Farm Bureau, the Grocery Manufacturers Association and the biotechnology industry. One of those lobbyists, a former deputy state agriculture commissioner, showed up to take pictures whenever the pro-labeling campaign staged public events, Henderson says.

As in New York, activists in Massachusetts say the advent of Vermont’s labeling law led to a new burst of support this year for their efforts to enact a similar law. On Beacon Hill, a GMO labeling bill garnered more than 75 percent of state legislators as co-sponsors.

Martin Dagoberto, the campaign coordinator for Massachusetts Right to Know GMOs, said the House Agriculture & Environment committee unanimously advanced the bill in March. It then sat in the House Ways & Means committee, where its chances appeared to fade near the end of the legislative session as federal action on the issue appeared likely to pre-empt any state law.

“Transparency opponents appear to have … convinced House leadership that this issue would soon be handled at the federal level,” Dagoberto said in an e-mail interview.

Although advocates of GMO labeling are often accused of being anti-science, Dagoberto knows the scientific perspective well: He studied biotechnology and genetics at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, graduating in 2006.

“It was there that I gained an appreciation not only for the immense promise of medical biotechnology, bur also for the incredible set of risks that the shortsighted and accelerated engineering of our food entails,” said Dagoberto. “When I learned about the federal government’s hand-off approach to regulating agricultural biotechnology, I became convinced that the only way forward must be with full transparency and informed participation of the public.”

The industry’s end run

In Washington, industry groups opposed to labeling had been pushing for most of the past two years for Congress to intervene to block Vermont’s law and any others that individual states might pass.

Last summer, the House voted 275-150 in favor of a bill, ironically titled the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act, to prohibit individual states from requiring labeling of genetically modified foods. Supporters of GMO labeling dubbed the bill the “Deny Americans the Right to Know Act” or Dark Act, and it stalled in the Senate.

This year, labeling opponents focused their efforts first in the U.S. Senate. The result was a “bipartisan compromise” backed by Sens. Pat Roberts (R-Kan.) and Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.), who are respectively the Republican chairman and the ranking Democratic member of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry.

Like last year’s bill, this year’s version barred states from requiring GMO labeling, thereby overturning Vermont’s law. But the new compromise also purports to establish a national system for disclosing information about genetically modified ingredients — except that the information doesn’t have to be disclosed on product labels.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (Tenn.) fast-tracked the bill, a maneuver that allowed the leadership to bring it to the floor for a vote without any witnesses giving testimony or amendments being considered.

Stander, of Rural Vermont, says both of Vermont’s senators — Democrat Patrick Leahy and independent Bernie Sanders — put forth amendments but were denied an opportunity to have them debated.

The bill passed the Senate by a vote of 63-30. On July 14, the House, without making any changes, passed the bill, officially titled “An Act to Reauthorize and Amend the National Sea Grant College Program, and for other purposes,” by a vote of 306-117. Despite an outcry from labeling opponents and a petition to the White House, the president signed it into law on July 29.

All of the senators representing New York and New England voted against the new federal law except New Hampshire’s two senators, Republican Kelly Ayotte and Democrat Jeanne Shaheen. House members representing Vermont, western Massachusetts and eastern New York all voted against the federal law except Rep. Elise Stefanik ®, who supported it. Stefanik, a freshman Republican, represents New York’s northernmost House district.

Advocates say one critical factor that allowed the anti-labeling bill to advance in the Senate was the decision of the Organic Trade Association, a trade group representing organic food producers, to support the so-called compromise legislation. The group cast the bill as the best deal that could be achieved — and even went so far as to criticize organic farm and food groups who opposed the bill, saying they were dividing the organic movement.

“What really turned the tide was essentially a betrayal by the Organic Trade Association, saying we can live with this, it is OK,” Stander says. “Our understanding is that once they did that, it provided enough cover for some farm-state Democrats in the Senate to vote for it.”

Many activists believe the Organic Trade Association backed the bill because of the influence of some of the association’s larger members — namely, major food-processing corporations that also own organic brands. Conventional food manufacturers stand to gain from the new law’s lack of full and accessible disclosure, while organic companies can continue to claim that only their products are, by definition, produced without genetically modified ingredients.

Devil in the details

What particularly galls labeling advocates is that the new federal law is being described by its supporters as a national standard for GMO labeling — but won’t require any information about GMOs to be placed directly on product labels. Advocates point out that all kinds of other data — nutrition information, a calorie count, ingredient list, and so on — are already printed on labels. Only for information about genetic engineering will consumers have to take extra steps beyond reading the label.

“There are no other types of mandatory disclosure that are not right there on the food package,” says Orell of GMO Free NY.

She says some national groups are looking into the possibility of suing on the grounds that the law is discriminatory, and hence unconstitutional, given that more than 100 million Americans do not own a smart phone. Many of those who don’t have low incomes, are elderly or live in rural areas.

For Stander, another concern is that the new federal law will limit the range of items subject to classification as genetically engineered. “The way they have defined bioengineering leaves out a whole host of products,” Stander says. “It will just lead to more confusion for consumers.” For instance, the law exempts products that do not contain “genetic material.” According to the FDA, oils, starches and purified proteins do not contain genetic material.

According to Liana Hoodes, formerly executive director and now a policy adviser for the National Organic Coalition, this means high-fructose corn syrup and canola, soy and corn oils — all routinely made from genetically modified crops — would be excluded from the disclosure requirement. Disclosure also will not be required if the genetic modification could have been achieved through conventional breeding. Such a claim would appear to be difficult, if not impossible, to prove and extremely difficult to police.

Hoodes says the National Organic Standards Board has convened panels to look at how to include newer genetic technologies in the definition of genetic engineering that is excluded from certified organic products. But the new federal law goes in the opposite direction. The latest technologies, like gene editing which does not involve the transfer of foreign genetic material from different species, do not fall under the new law’s definition of genetic engineering. Hoodes believes the implications are great. She says, “The law that was passed is likely to redefine what GMO is — and even what organic thinks is a GMO.”

Building public awareness

Despite the defeat in Congress, Stander says the pro-labeling campaign had had a huge impact — and the campaign’s effort to educate the public is paying off. She cites recent survey research that found a large jump in the number of people who are able to identify the five crops most commonly produced with genetic engineering.

Stander says there’s another important measure of success: The tenacity of her state, one of the country’s smallest, leveraged national change. “We did persuade major corporations to label their products or to change the formulation of their products in response to consumer demand,” she says.

When General Mills announced that it would reformulate its classic Cheerios brand, Stander says the group Moms Across America ran a massive social media campaign, and the company decided to remove genetically modified ingredients from the cereal. The food company didn’t acknowledge that this grassroots activism played a role in its decision, however.

Though Stander says she is frustrated by the passage of the new federal law, she remains energized by what has already been accomplished. “This issue isn’t going away,” she says. “Too many people who are aware will continue to vote with their dollars.” She and others who’ve campaigned for labeling say they will continue to organize their grassroots supporters to press for fuller disclosure as the U.S. Department of Agriculture develops rules to implement the new federal law.

“We will need to help people participate in the comment periods and other input opportunities during the rulemaking process,” says Dagoberto. And Hoodes says she sees “a lot of pressure points coming up ahead” in the federal rulemaking process. “We’re trying to look at all these bads as opportunities to keep the issue fresh in the public’s eyes,” she says. “There will be opportunities for publicity at every stage of the way.”

Stander also suggests that focusing on the details of the new law might help create public pressure to improve the law. “As the USDA’s rulemaking process goes forward, more of the flaws with the law will be revealed,” says Stander. “It will become clear how vague and unclear it is, how many loopholes it has. … We may be able to have some influence or shine a light on the problems.”

She predicts, however, that the next presidential administration probably won’t be “particularly consumer-oriented.”

“GMO labeling will not be restricted to the political arena”

On Aug. 18, Congressman James McGovern (D-Worcester), speaking in Northampton, Mass., called for repealing the new federal law — an effort Dagoberto said the Massachusetts coalition would support.

But action on GMO labeling will not be restricted to the political arena. Nearly 500,000 people have already signed up to boycott brands that refuse to label products genetically modified ingredients — as well as those organic companies that supported the new law.

“Companies that don’t disclose which products contain genetically engineered ingredients are going to pay a price for that with consumers,” says Dagoberto. “We are choosing whether the future of food and agriculture will be in the hands of the people or in the hands of multinational chemical corporations.”

Henderson, the organic farmer from western New York, says she supports GMO labeling in part because she wants people to be able to avoid food that contains glyphosate, the herbicide better known by the brand name Roundup. Last year, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen. The weed killer is used in tandem with the most popular types of genetically modified crops, Roundup Ready corn and soybeans. Its use has skyrocketed since these herbicide-resistant crops first went on the market. The USDA also has significantly increased the allowable levels of glyphosate in food to accommodate the actual residual levels that result from heavy spraying of these crops.

The organic movement has played a crucial role in propelling GMO labeling forward. Hoodes says that even though this isn’t the group’s focus, the National Organic Coalition made a commitment to work on the issue “because we knew what was at stake — the right to know what’s in our food.”

“Organic means no GMOs — and that’s a bona-fide label,” says Hoodes. “But the absence of GMOs is not the same as organic.”

For Dagoberto, GMO labeling could be the gateway to an alternative future. “I see GMO labeling as one avenue for food sovereignty,” he says, “people reclaiming control over what our food supply looks like.”

(“Still Seeking the Right to Know” was originally published in the Hill Country Observer and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the author. Main image is property of Crowley Photos courtesy of the Vermont Public Interest Research Group.)

(Correction: An earlier version of this post mistakenly reported Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), speaking in Northampton, Mass. on August 18, called for repealing the federal law. It was in fact Congressman James McGovern (D-Worcester) who made that statement. This has been corrected in the text.)