This spring, after gathering on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northwestern Minnesota and then in Colorado, tribal “hempsters” are working toward a renaissance of the plant that once clothed much of Europe and North America. Tribal hemp growers from the Meskwaki, Lakota, Menominee, Mandan, Hidatsa, Colville and other Native nations are planting the seeds of a new economy — responding with an innovative and holistic approach to the many challenges Native and non-Native communities face.

These new, young tribal leaders are taking a place at the table of the $700 million U.S. hemp industry — an industry that can literally transform much of the material, food and energy world. As hemp returns as a viable part of food, clothing, housing, medicine and fuel systems, tribal hemp leaders are keen to not only be a part of the industry, but to transform their communities.

In early April, at the NoCo Hemp Expo in Loveland, Colo., the near limitless potential of hemp was on display. An estimated crowd of 10,000 curious enthusiasts, among them Native people, crowded into the convention center to view hemp in forms you can fuel your car with, eat in chocolate or pesto sauce, slather on as shampoo, and wear. The trade show was not about “bongs” and tie-dye — rather, it featured the latest harvesting and processing equipment, innovations in hemp farming and up-to-date regulatory analysis.

The industry has certainly arrived in good time.

Muriel YoungBear, a member of the Meskwaki Nation in Tama, Iowa, is a second year attendee of the expo. Currently a University of Kansas graduate student studying business, she’s been attending hemp-related conferences, networking with industry leaders, visiting Colorado growing operations and working within tribal economic development circles to become an educational resource for native nations. While looking for alternatives to fossil fuels, timber, plastics and cotton products, YoungBear became inspired by hemp.

“Initially, I started this journey after seeing the unsustainable business practices our tribal communities are dealing with and I am determined to find an alternative. Hemp is the way to do that,” says YoungBear. She adds, “I want our communities to be a place people run to, not from.”

Understanding that education about the plant’s potential was “the one piece missing in Indian Country,” YoungBear began a social media campaign to publicize speaking sessions with her tribe, water protector camps and Iowa senators.

Out West, Dustin Finley has been working with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in north-central Washington to establish an industrial hemp project. This past year, the tribe grew 60 acres of hemp in the state — the largest grow by any tribe. “I want to make our communities one again,” says Finley.

Like YoungBear, Finley sees hemp as a way to rebuild a local tribal economy and bring people back. “I want a place for people to come home — to bring your knowledge back to your people rather than just leave it,” he says, referring to the “brain drain” and diaspora many reservations face. “I have two young sons… and I’m scared of what’s out there,” says Finley. “Hemp can change the world.”

Along with YoungBear and Finley, Rosebud White Plume, Marcus Grignon and Waylon Pretends Eagle have launched the Intertribal Hemp Association—a new organization intended to educate Native communities about hemp and work to create collaborations for the future of the tribal hemp industry. For them, hemp is about healing and social change, not money.

YoungBear’s interest in hemp was piqued three years ago. Then an undergraduate student at Haskell University in Kansas, she began studying with the college’s indigenous scholars. She read books with Michael Yellowbird and took food sovereignty internships that focused on decolonizing food systems with Dan Wildcat. Among the plant’s 10,000 known uses, hemp, it turns out, is an excellent source of nutrition and amino acids. “I want to feed the warriors,” says YoungBear.

Waylon Pretends Eagle is from Mandaree, N.D., population 596, near the Ft. Berthold reservation — also known as the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara (MHA) Nation. The reservation is in the midst of a fracking boom: Oil royalties are paid out to some families on the reservation and tribal coffers are filled with oil money. At the same time, ground water, plants and animals are suffering from the fracking process. “My family actually benefits financially from fracking,” says Pretends Eagle, “but I’d like to push us all forward.”

Pretends Eagle sees hemp as part of his own healing as well. “I want to heal myself by growing good medicine. I have some trauma from my childhood and this is what I need,” he says.

The medical benefits of hemp come from, in part, the cannabinoids contained within the plant. Over the centuries, these healing properties have been documented as treating a wide variety of human health conditions. Cannibidiol, or CBD as it’s commonly known, is one of over 100 Cannabinoids found in Cannabis sativa L.—the binomial name of the hemp plant. Although CBD is a major medicinal constituent found in hemp’s many varieties, it should not be confused with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) — the one that gets you “stoned.” Hemp and marijuana come from the same cannabis species, but they are genetically distinct and the cultivation methods are different.

Compared with THC, Cannabidiol is not psychoactive in healthy individuals and is considered to have a wider scope of medical applications. These applications include, but are not limited to, the treatment of epilepsy, multiple sclerosis spasms, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, nausea, convulsion and inflammation, and inhibiting the growth of cancer cells.

Hemp is also known to have properties that bioremediate toxins in the soil and air (i.e. help clean up) and sequester carbon — both of which could help address the environmental challenges taking place on the Ft. Berthold Indian Reservation and elsewhere. As such, hemp is viewed by Pretends Eagle and other tribal leaders as a key in healing not only people, but Mother Earth.

An intergenerational commitment

Marcus Grignon, from the Menominee Tribe in Wisconsin, is the campaign manager for Hempstead Project Heart. Founded by the legendary philosopher and writer John Trudell (Santee) and songwriter Willie Nelson in 2012, the collaboration seeks to raise awareness regarding the benefits of hemp for both people and planet. Following Trudell’s death in 2015, Grignon pledged to carry on the organization’s work and continues to advocate for the Menominee’s cultivation of hemp.

This work has not been easy. As recently as 2015, the Menominee hemp crop was seized by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). The right to grow hemp has been mired in bureaucratic controversy for decades but, thanks largely to the tireless work of its advocates, attitudes in states across the country are changing.

Another leader of tribal hemp’s “Old Guard” is Rosebud White Plume’s father, Alex, from Manderson and Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. For 16 years, from 2000 to 2016, he and other tribal members in the state fought to push the hemp industry forward. (His battle to grow hemp on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is an epic story in its own right.) In short, although Pine Ridge and the Navajo Nation had passed ordinances to grow industrial hemp, tribal crops continued to be seized and the federal court barred the White Plume family from planting hemp.

In March 2016, however, the U.S. District Judge of South Dakota, Jeffrey L. Viken, lifted the injunction that stopped White Plume from growing hemp on his land by Wounded Knee Creek. He produced his first crop again in 2017. Now, Rosebud White Plume, Alex’s daughter, has taken up much of the hemp work for the family. Like the other young people in the second generation of this renaissance, she looks forward to a brighter future thanks to the hemp revolutionaries of the last decades.

Though Trudell did not live to see the full renaissance, his legacy is flourishing. In late 2017, the state of Wisconsin also legalized industrial hemp. And now that spring is coming to the North Country, the Menominee, Oneida and the St. Croix Band of Ojibwe all plan to grow this year.

Unlike tribal gambling, the economic boon hemp offers indigenous communities includes health and environmental benefits. Wealth, after all, is more than money — it is wellbeing. At a Native gathering at the NoCo Hemp Expo, Lavonne Peck, a former tribal chairwoman of the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians, spoke of the promising role CBD is playing in assisting those suffering from opioid addiction. “It’s the future,” she says. “Hemp is what the world needs. Hemp is the way.”

Indeed, more mental health counselors are looking toward hemp as a part of a holistic treatment for addictions and trauma. Wearing an outfit made entirely of hemp, Dionne Holmquist, the founder of Hemp Quest Ventures of Colorado, also attended the gathering. With a long career as a counselor, she says, “I wanted to do holistic healing, not treatment. That’s what I learned as an addiction counselor. We were just treating people and not healing them.” Inspired by Alex White Plume, Holmquist’s experience motivated her to do more and eventually led to her current role leading multiple hemp initiatives. She and her company will work with tribes to move their efforts forward.

Hemp economics and big pharma

Tribal and other hemp growers are (and must continue) doing all they can to ensure that “Big Pharma” does not control the future of hemp. This is, after all, a medicine you can grow in your yard. But there is undoubtedly money to be made.

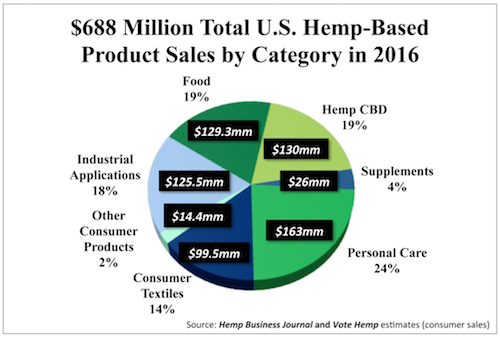

Hemp Business Journal estimates the total retail value of all hemp products sold in the United States to be at least $688 million for 2016. The data demonstrates the hemp industry is growing quickly and according to Sean Murphy, the Journal’s founder and publisher, sales are projected to be nearly $2 billion by 2020. The surge is expected to be led by hemp food, body care and CBD-based products.

One example of the pending boom is the fact that pharmaceutical companies are continuing to develop innovative cannabinoid based drugs. In the United States, GW Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ:GWPH) has received Orphan Drug Designation from the FDA for its CBD-based drug Epidiolex. The drug will be used to treat a variety of degenerative and other illnesses including tuberous sclerosis complex and infantile spasms — both severe infantile-onset, drug-resistant epilepsy syndromes.

Big pharma stands to profit well: Sales of Epidiolex are slated to begin in 2018 or 2019, and are projected by Hemp Business Journal to reach $120 million by 2020. If these forecasts for Epidiolex prove accurate, sales of the drug will represent nearly 7 percent of total hemp industry sales by 2020 — an estimated $1.8 billion market.

For those concerned about any new regulations that would limit tribal and other national hemp markets, most industry and legal analysts are not worried. “That train has left the station,” says longtime environmental and Native American advocate Don Wedll. Now in his third year of growing hemp in Minnesota, Wedll says, “You can buy CBD’s at Walmart.” To further cement this sentiment, the Hemp Farming Act of 2018 was introduced on April 12 by Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky). The legislation, which would amend the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 to once again allow hemp production, was quickly given a second reading by the Senate and is expected to pass.

With tribes like the Anishinaabe, Crow, Oneida, Odawa, Menominee, Navajo and Omaha interested in industrial hemp, it is clear that the renaissance of hemp is now. This spring, a planting in Native communities brings promise. With it, a new collaboration is growing in indigenous nations. Some tribes will grow, others will enact regulatory authority, and more tribes will come to the table in what promises to be an economy that can change many facets of our lives.

The plant is here to stay.