On an evening in late May, a group of Chicago small-business attorneys, urban farmers, environmental community organizers, and food policy makers gathered at a café in Chicago’s South Loop to discuss barriers to building a local, sustainable food movement in Chicago and Illinois at large.

The Sustainable Economies Law Center (SELC) — an Oakland, California-based nonprofit organization that provides legal tools for communities to build alternative, grassroots economic structures for food, housing, and energy — sponsored the event in part to gauge interest in establishing a Midwest SELC branch in Chicago. According to the event’s moderator, Chicago and Illinois have seen “a lot of activity in the local foods movement” in recent years, particularly within the upmarket restaurant industry whose relatively small scale is well matched with that of small farms.

Yet, the farm-to-table dining movement is a pittance relative to Illinois’ overall food consumption. Residents of Illinois spend around $48 billion on food each year, and the vast majority of that goes to food imported from out of state.

“We’re such an agricultural state, but in Central Illinois, for example, we only [give] 0.1 percent of our food dollars directly to our farmers,” says Rebecca Osland, one of the events panelists and a lobbyist at the Illinois Stewardship Alliance, an organization that advocates for sustainable, local, and socially just food policies in Springfield.

Osland sees the paucity of small farms growing diversified crops as a major barrier to the local foods movement in Illinois, the country’s fifth largest agricultural state economy.

Today, there is little incentive for young people to go into sustainable agriculture. Land access, much of it controlled by large agribusiness, is not cheap. Though programs such as the Department of Education’s Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program and the Illinois Treasury Department’s Ag Invest Linked Deposit Program exist to subsidize sustainable farming practices for new farmers, Osland says that farming communities in rural Illinois continue to experience a mass exodus into cities.

“We need a whole lot more farmers. We don’t have enough farmers growing food that people can just eat. They grow plenty of corn. They grow plenty of soy, but we would need tens of thousands of farmers to convert over to growing diversified crops to meet the demand [of a local foods movement]. We just don’t have the supply,” says Osland.

The industrial scale of today’s farms makes the diversification of fruits and vegetables necessary for a local foods movement highly impractical. Illinois’ big landholders, following a desire to reduce costs and increase profits, built an agricultural industry based on the idea of producing a few crops on a massive scale. Consequently, corn and soybeans account for over 80 percent of farm cash receipts in Illinois.

“It’s all based around that industrial scale, and that provides economies of scale so that [farmers] can produce units for cheaper than those working on a smaller level. That puts out the smaller farms competitively,” says Osland.

Small farms and farmers willing to work them are not the only missing piece in the equation. There are a number of infrastructural gaps between the food production and consumption sides of the local food economy. For the restaurant industry, because the scale is so small, the farm-to-table pipeline is relatively straightforward. But bridging the food production and procurement sides of the supply chain becomes a lot more challenging on a massive scale without processing facilities and wholesalers that aggregate the food produced on small farms.

“We don’t have enough meat processing facilities. We don’t have enough grain silos. We don’t have the appropriately scaled logistics, the transit, the food hubs. There’s a lot of talk about how we aggregate, how we get a lot of small growers who combine what they produce and make it efficient enough to get to market,” says Osland.

Demand, quality and cost

Jose Oliva, another panelist at the event, and Co-director of the Chicago-based Food Chain Worker’s Alliance—a group whose work focuses on food procurement and labor practices — explained how weaknesses in the supply chain make ethical food purchasing policies difficult, especially for large-scale food providers such as Chicago Public Schools (CPS).

“[In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), for example], the poultry provider used to be Tyson because they were the only ones that could meet the demand, even [though] Tyson was providing chicken that was riddled with antibiotics…that are incredibly destructive to the environment and workers [were] toiling — literally losing fingers because [they are processing] one-hundred and forty birds a minute” says Oliva, who is currently working to get Chicago’s first food purchasing policy ordinance passed in city council, one that follows Los Angeles’s model.

Workers at a meatpacking plant in Nebraska. (Photo: foodchainworkers.org)

“Even though we could prove that Tyson was not a good fit for LAUSD, there was no other supplier that could meet the demand. They [need] 600 thousand meals everyday. That’s a huge amount of food that they’re serving and no one else could meet that demand. It took three years to actually get to the place where we could identify a vender that was able to aggregate organic chicken where you can trace the working conditions and prove the claims that it had no antibiotics in it,” says Oliva, who is now working to find a supplier capable of bring local, sustainable foods to CPS cafeterias.

“Right now, the food that the city of Chicago buys basically has one criteria, which is that it has to be the cheapest stuff out there. That is the only criteria they have for the food that is being fed to our kids in public schools and so that food could be brought to this country via slave labor for all they care,” says Oliva who looks to his native Guatemala as a model for a sustainable, local foods economy that works.

“It isn’t brain surgery. My uncle organizes small farmers [in Guatemala],” Oliva says. “They have plots that are for them… and then they have plots for trading. They trade with other farmers. They aggregate that and they take it to market and they make cash and the cash comes back to the community and the community buys things for themselves including infrastructure.”

Race, local economies and the food industry

Several of the event’s attendees lamented racial and economic inequities in the local foods movement. While immigrants and people of color make up the majority of the labor in the food economy — the food system accounts for one sixth of the country’s workforce, many who are people of color and immigrants — local, sustainable food remains largely inaccessible to these communities.

“[Food industry jobs] are the gateway for immigrants. When they arrive in this country, they are either farmworkers if they were rural in their home countries, or they’re restaurant workers if they were urban. You walk into any restaurant in the city of Chicago and I will put some money on the table if you don’t have an immigrant in there somewhere. And same thing with the current farm structure — there are always immigrants there,” says Oliva.

Molly Medhurst who co-owns Chicago Patchwork Farm, an urban farm with a sliding-scale business model, in the city’s gentrifying Humboldt Park neighborhood, said that building an organic farm in Chicago has forced her to confront many difficult questions about who the local foods movement is for and what impact it has on low-income, immigrant communities.

“Building a farm seems like this really great innocuous thing, but it can have consequences on a neighborhood, especially a neighborhood made up of people who don’t look like me. You know, I’m white, and I’m building a farm, and the people who are coming to my farm are majority white …and I’m trying to deal with that all the time,” says Medhurst. Since Italian and Polish immigrants left the neighborhood in the 1950s, working-class Puerto Rican and Mexican communities have dominated Humboldt Park, on the city’s Northwest Side.

Vivi Moreno, a community organizer with the Little Village Environmental Justice Center grieved that the entire food industry is plagued by environmental racism. “Black and Brown folks don’t own the land, they work the land. It is hugely because of a system of racism that our food system looks the way that it does,” Moreno says.

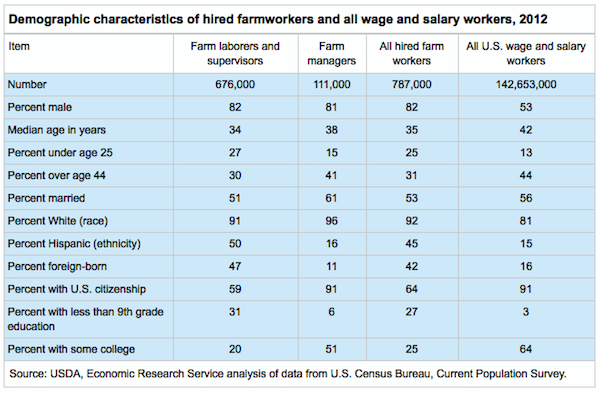

According to the USDA, Latinos made up around half of U.S. farm laborers in 2012, but only 16 percent of farm managers. White people, on the other hand, accounted for 80 percent of managerial positions.

Osland and Oliva are optimistic that organizations such as theirs can work to systematically implement the local foods movement — a movement that until now has remained a privilege of those with resources.

Late last month, the Illinois legislature voted unanimously on the Healthy Local Food Incentives bill, part of the Farm Bill, that will provide double-value coupons to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) users for fruits and vegetables at farmers markets — alleviating some of the burden from farmers and low-income communities.

“I know this sounds dramatic but it is actually true that agribusiness is destroying our planet in more ways than one,” says Oliva. “We need to continue to organize resistance to that but at the same time we need to create an alternative and it has to be something we’re able to then demonstrate has an impact not just at the local level, but in the entire supply chain.”