West Virginia, “Identity Decline” and Why Democrats Must Not Look Away From the Rural Poor

Lauren Kaori Gurley

When the Economic Development Authority of McDowell County in West Virginia announced the opening of a privately-owned prison in 2006, hundreds of laid-off coal miners expected jobs would flood into this rural county, where only one in three people is employed. In the following months, those jobs did come but a significant portion went to commuters from more prosperous counties in West Virginia and neighboring Virginia. The reason? Many McDowell applicants tested positive for opioids in initial drug screenings and had been marked ineligible for hire.

In late September, I made the four-hour drive from Charlotte, N.C. to McDowell County, W.V., (pop. 19,835) — the 6th lowest income county in the United States and the poorest in West Virginia. Over the past year, I had written several articles about poverty in rural America, and knew full well the effect of deindustrialization on rural communities. Still, entering into McDowell County from the sleepy micropolitan towns of southwestern Virginia felt a bit like crossing a national border.

Hundreds of abandoned houses, schools, banks, restaurants and motels line U.S. Highway 52, McDowell County’s winding two-lane artery known as Coal Heritage Road. At midday, the unemployed sit out on their front porches overlooking the highway, smoking cigarettes and waving to passing cars. The political campaign ads running along the hollows — “Make West Virginia Great,” “Bring Back Coal,” “Trump Digs Coal”— painted a picture of the county’s political trajectory. On November 9, 75 percent of McDowell County voters turned out for Donald Trump.

“There’s nothing left in this town. There’s no business left,” Ed Shepard, 93, told me when I spoke to him at his Union 76 station in Welch, the McDowell County seat. “I’m just whiling away my time now… [I have] two or three clients a week.”

The decline and fall of a single industry town

McDowell County sits at the top of many national poverty rankings. Of the families in McDowell who have children, 40 percent live in poverty, compared with 10 percent nationally. (In 2016 the U.S. government defined poverty as an anual income of $24,300 or less for a family of four.) Opioid addiction is rampant, as are chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and Black Lung — a respiratory disease of miners caused by exposure to coal dust. The average man in McDowell County does not live to be 64 — 13 years below the U.S. average.

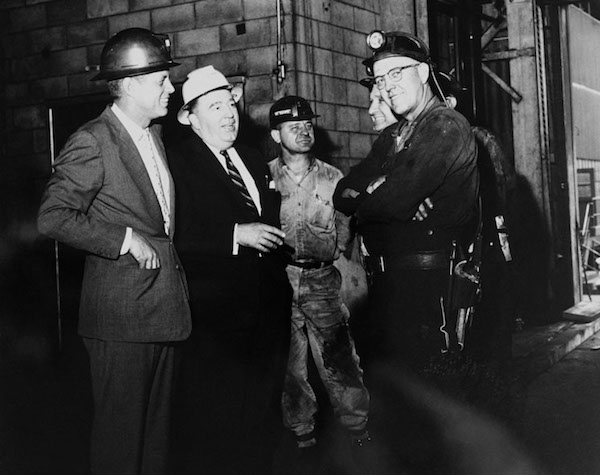

In the spring of 1959 — 57 years ago — Sen. John F. Kennedy (D-Mass.) made a presidential campaign stop in McDowell, during which he touched on many of the same issues that the county faces today. He said America had been “caught in the backwash of economic cycles, shifting markets, and automation.” Shepard, 36 at the time, remembers Kennedy’s visit to Welch, but recalls that the decline of the coal industry had only begun to take shape. “I shook hands with him. The motorcade was going around, and it stopped right there,” Shepard says, pointing out of his shop window at the empty street.

May 9, 1959 — John F. Kennedy and Sen. Jennings Randolph (D-W.V.) talk with Harry Switch, John Bucciarelli and an unidentified miner at the U. S. Steel Cleaning Plant in McDowell County, W.V. (Photo: Jennings Randolph Collection / West Virginia State Archives)

Every family in McDowell, the southernmost county in West Virginia, has been impacted by the decline of the coal industry. The aftermath of General Motors’ downfall in Detroit is comparable to loss of the coal industry in McDowell. In 1950, McDowell was the leading producer of coal in the state, and the population was nearly 100,000. But the county underwent a rapid outward migration beginning in the late 1950s, following the mechanization of the coalfields. Today McDowell’s population sits at just over 19,000 — nearly the same as it was in 1900.

“You put one machine in there and you replace 200 men,” Shepard says. Though Shepard never wanted to work in the mines — his father was killed in a mining accident — he says the sharp decline in coal mining jobs affected his business. “The economy went down, down, down,” Shepard says. “Much of your population here now is on welfare. We’ve still got coalmines, but they’re being run with machines, so they don’t need all the people they once did.”

Many West Virginians blame more recent pay cuts and layoffs in the coal industry on the Democratic Party’s efforts to regulate coal emissions. Once a stronghold of unionized Democrats, West Virginia flipped political affiliations during the 2000 election, and has continued to prefer Republicans like George W. Bush and Mitt Romney whose policies focused on recovering rather than eradicating the coal industry. For West Virginians, Trump held a messianic appeal. Every single West Virginia county went to Trump, who campaigned heavily throughout the state, promising to repeal President Barack Obama’s fossil fuel emission standards.

Donald Trump campaigns in West Virginia wearing a hard hat. (Photo: The Last Refuge)

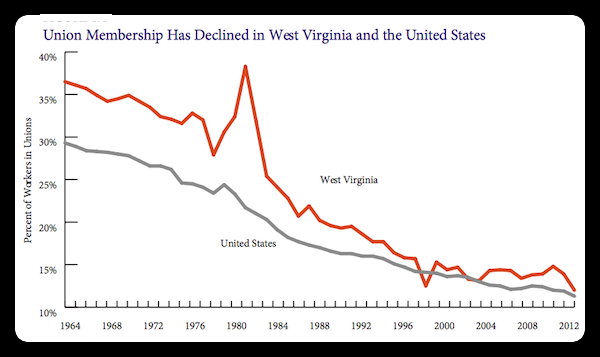

Roy Williams Brown, 23, began mining for Alpha Natural Resources two weeks after he graduated from River View High School in 2011. But he says the possibility of losing his job is ever-present and one of the reasons unions are not as strong as they used to be. In February 2016, West Virginia passed “right-to-work” laws that severely weakened unions by allowing workers to opt of out of paying union dues.

“The pay and benefits have dropped tremendously. People are getting laid off,” Brown tells me while waiting in line at BW’s Barbershop in Welch. “My pay went from $31.50 an hour to $26.50 an hour in three years.” Between 1981 and 2015, union membership in West Virginia took a dive from 38 percent to 12 percent of workers. The scarcity of mining jobs in West Virginia has allowed coal companies to hire non-union miners who will work for lower wages.

(Source: Hirch, MacPherson and Vroman (2001) and Unionstats.org)

For generations, the men in Brown’s family have worked in the McDowell County coalmines. But, after being laid off last year, Brown’s father moved to Florida. “You never know what’s going to happen. Mines are shutting down. The ones who have been laid off are just unemployed,” Brown says. He got married after high school, but he and his wife, a nurse, are waiting for greater job security before they have children.

Unlike highly diversified metropolitan economies, rural economies are typically dominated by a single industry — oil in east Texas, corn in central Illinois, potatoes in eastern Idaho. “The lack of economic diversification is a common theme with rural economies,” says Lisa Pruitt, a professor of law at University of California Davis, whose work focuses on rural livelihoods. “In Appalachia, that lack of economic diversification is wrapped up with the dominance of coal, and so whenever anything threatens the coal industry, then that threatens further economic collapse.”

Built in 1908, to dig and load coal onto trains in Gary, W.V., the machine on the left required three men to do the work of 50. On the right, completed in 1978, the Bagger 288 is used to remove “overburden” when strip mining. Until the 1990s, it was the heaviest land vehicle in the world weighing in at 13,500 tons. (Photo: Lewis Wickes Hine / Kamil Porembinski)

Life after coal

For decades, poverty rates in the United States have been higher in rural areas than in urban ones. In 2011, 85 percent of persistently poor counties in the United States were non-metropolitan — the majority of these counties are clustered around Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta and the New Mexico/Arizona border. The United States Department of Agriculture defines “persistent poverty counties” as those in which more than 20 percent of the population hads been lliving below the poverty line for over three decades.

The loss of coal mining jobs in McDowell led to the deterioration of the housing stock, roads and other infrastructure that coal companies built and maintained throughout the first half of the 20th century. “Originally, in McDowell County, [coal companies] put in the housing for the miners and they put in the water and sewer systems. These have greatly deteriorated,” says Jeff Johnson, community development director at West Virginia’s Region One Planning and Development Council. “I have a number of communities that, unfortunately, [still] straight pipe their raw sewage into creeks and waterways.”

Johnson has worked for 17 years to attract industries such as tourism, farm-to-table farming and prisons to West Virginia’s six southernmost counties. “There’s a big thrust to diversify the economy,” he says. Efforts to expand the tourism and four-wheeling industries have been seen as the most promising, but the region’s rugged topography and decaying infrastructure turn many businesses away.

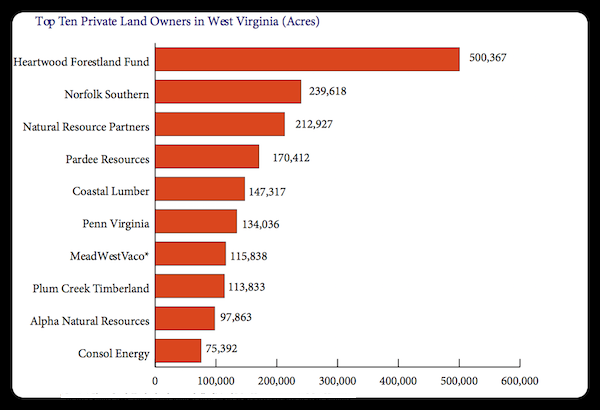

Out-of-state coal companies own millions of acres in West Virginia, making it difficult for new industries to develop the land. In McDowell County, ten landholders own over 60 percent of private land. Norfolk Southern, a Virginia-based railway company that also manages coal, natural gas, and timber resources, owns nearly a quarter of all private land in McDowell.

(Source: wvpolicy.org)

Those who are unfamiliar with rural economies might wonder why the people of McDowell do not give up on coal. Why do they continue to see coal’s revival as the panacea to hard times — despite all the evidence that coal jobs are not coming back. “Everyone associates good times with coal. It’s just the way people think, because it’s just what they’ve known,” says Paul Rakes, a professor at West Virginia University’s Institute of Technology.

Since topographical engineers from the Civil War first began to exploit Appalachia’s coal reserves in the 1870s and 1880s, the coal-mining industry — much like agriculture and other extractive industries dominant in rural economies — has followed a boom-to-bust cycle. Miners have a saying: “Coal mining is feast or famine.” When the demand for fossil fuels is high, coal-mining jobs with solid middle-class incomes flow into the community. “As an extractive industry,” Rakes says, “it’s the first to be affected by an economic downward trend, because you’re supplying the natural resource. When other areas of the economy begin to slow, it’s going to slow coal first, because they don’t need those raw materials as much anymore.”

Despite the overall downward trajectory of the industry over the past 60 years, coal experienced upswings as recently as George W. Bush’s presidency. This is one reason McDowell clings to the hope for a comeback. Compared with coal mining, jobs in tourism and agriculture are less attractive as they are seasonal and mark “something of a downward mobility” in terms of income for former miners, says Rakes. In 2015, coal miners in the United States made an average annual salary of $55,550.

“[In the past], school, for a lot of students, wasn’t as important because you could get a job in the coal mines,” says Frazier McGuire, principal of River View High School in western McDowell County. “You didn’t have to have a high school diploma, and you still made a pretty good salary. But over the last 15 to 20 years, it has gradually gotten to the point where you can’t do that anymore. McDonalds and fast-food are about it.” In McDowell, 5 percent of adults have college degrees and 65 percent have high school diplomas. Like prison jobs, many teaching positions in the McDowell County School District are filled by people from outside of the county.

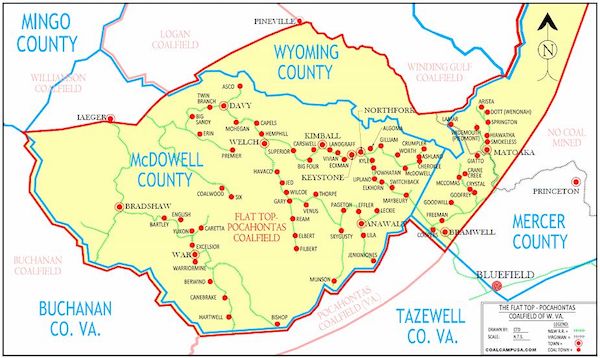

A coalfield map of McDowell and surrounding counties. (Image: coalcampusa.com)

“We don’t have people who can pass the drug tests or you have a population that’s not prepared to take the jobs,” says Nelson Spencer, the superintendent of McDowell County Schools. During some years Nelson is forced to leave teaching positions unfilled or hire teachers certified in other subjects. “I would much rather have a math certified teacher teaching math than a social studies teacher teaching math,” he says.

Does West Virginia matter?

The steady loss of coal mining jobs in Appalachia marks a larger shift in the American socioeconomic landscape. Blue-collar jobs that do not require college degrees are no longer easy to come by. Since 2000, 5 million manufacturing jobs have been lost nationwide, and in Obama’s first term alone, 50,000 coal-extraction jobs. The long-evolving transition from an economy that produces goods to an economy that produces services has triggered what Arlie Hochschild, author of Strangers in Their Own Land, calls “identity decline” for white working-class rural Americans, and an intractable nostalgia for a bygone America.

A McDowell County resident talks on her phone outside her house on Highway 52, also known as Coal Heritage Road. (Photo: Lauren Gurley)

Often pushed into the shadows of the national poverty debate, poor rural Americans took the spotlight throughout the 2016 presidential elections, as journalists scrambled to explain the advent of Donald Trump. “The rural poor and rural working class kind of come back into the national consciousness during the election season,” says Pruitt, the University of California — Davis professor. Yet, many establishment Democrats and Republicans alike blame a “culture of ignorance” and a “culture of fear” for the “backwardness” of rural Americans, and in doing so they skimover the economic roots of rural poverty. Despite the Democratic Party’s commitment to fighting inequality, its stance towards working-class whites in rural America is often defined by disavowal and contempt. “[Poor rural whites] have become sort of a scapegoat,” Pruitt says.

Nearly everyone I contacted and interviewed in McDowell expressed concern about speaking on the record about their community. Many declined to be interviewed, noting that reporters often come into the county seeking to capitalize on its poverty through negative portrayals of the local people and culture.

“I don’t care what people say. I don’t care what people put in the books. You will never meet a better bunch of people than the people of McDowell,” says Monique Rash, 41, a nurse at the Tug River Health Clinic in Welch.

Rash, who is African-American and a native of McDowell County, left home in the early 1990s to study nursing, but her ties to the community were too strong for her to stay away — a sentiment felt by many among the county’s small professional class. “I could go elsewhere, and make more money or do whatever, but it feels good to me to be here,” says Rash.

Like many other McDowell residents I spoke to, Rash questions the intentions of politicians and businesses that come into McDowell promising to bring change. “I try to stay out of the whole politics thing, but a lot of coalmines were shut down because of this ‘clean coal.’ You got to have all these guidelines,” Rash says.

Many progressive Democrats have difficulty stomaching the rural poor. Their values are seen as diametrically opposed to the Left’s commitment to the environment, racial and gender equality, immigration and prison reform. This ideological disconnect has, with the recent exception of Senator Bernie Sanders’s campaign for president, blinded the progressive movement to the possibilities of what can be gained by uniting the urban and rural poor. If the polarization of America’s rural and urban working classes is the greatest lesson for Democrats in the 2016 election — as many progressives have argued in the aftermath of Trump’s presidential victory — then mending this rift should be the movement’s foremost assignment over the next four years.

The publication of this story was supported by a grant from the Marguerite Casey Foundation’s Equal Voice Journalism Fellowship Award.