ON ELECTION DAY, THE CEMETERY WHERE SUSAN B. ANTHONY IS BURIED had to extend its hours for those wishing to cover her tombstone with “I voted” stickers. Many of us thought that the endless slog would be over, not just the 16-month slog of this curdled, rancid campaign, but also the 144-year slog for a woman to be taken seriously as a presidential candidate, earn the nomination of a major political party and actually win. As a feminist roughly of Hillary’s vintage, who participated in one of the most significant social movements of the 20th century — the Women’s Liberation Movement — I felt we were poised to break this barrier after all these years.

Devastatingly, even though Hillary won the popular vote, in her stead we got a publicly misogynistic, racist, nationalist, massively uninformed self-styled autocrat.

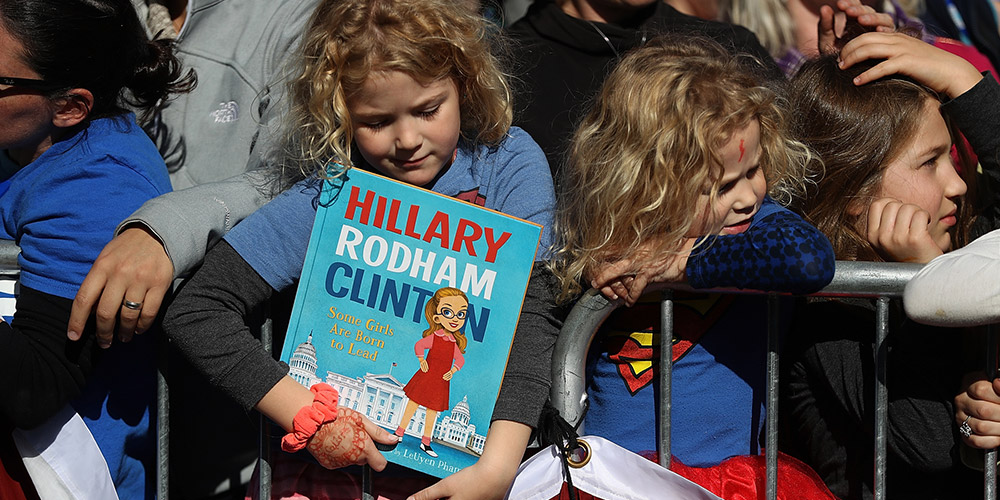

Hillary was a flawed candidate, and exit polls suggest she failed to galvanize, as Obama had, African Americans, Latinos and young people. But in considering what led to this loss, let’s not forget how sexism, and sometimes rank misogyny, have thwarted women’s quests to lead our country.

The suffragist Victoria Woodhull was the first woman to run for president, in 1872, representing the Equal Rights Party. In 1870, the passage of the 15th Amendment had granted African-American men the right to vote, but women of all races remained disenfranchised. So Woodhull herself, thwarted by sexism, hoped to combine the campaigns for women’s equality and racial equality. Today that seems more pressing yet imperiled than ever.

In 1964, Maine Republican Margaret Chase Smith—whose candidacy was an object of merriment among many in the nearly all-male White House press corps—ran in the primaries against Barry Goldwater, although she didn’t win a single nominating contest. She had been the first member of the Senate to stand up against Joe McCarthy and asserted in her 1950 “Declaration of Conscience” speech, “I don’t want to see the Republican Party ride to a political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny—Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry and Smear.” How prophetic.

The first African-American woman elected to Congress, the outspoken feminist Shirley Chisholm, ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972 and won 152 votes at the convention (compared to McGovern’s 1,728). She knew she didn’t have a chance but wrote the next year, “What I hope most is that now there will be others who will feel themselves as capable of running for high political office as any wealthy, good-looking white male.” She stated, repeatedly, that sexism had impeded her more than racism: “The emotional, sexual and psychological stereotyping of females begins when the doctor says, ‘It’s a girl.’ ”

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Geraldine Ferraro, as vice-presidential nominee, was asked on Meet the Press: “Do you think the Soviets might be tempted to take advantage of you simply because you’re a woman?” Pat Schroeder was criticized for choking up when she withdrew from the presidential race in 1987, because it would reinforce the notion that “women were too emotional to govern.” Carol Moseley Braun and Elizabeth Dole tried, too. Of Dole, an article in New York Times Magazine noted that her “sugary Southern charm” would not carry her very far and asked “who wants a magnolia” for president?

So now, here we are, at the end of a long campaign in which the Republican candidate has injected the body politic with massive new doses of racism, xenophobia, attacks on a free press, conspiracy theories, and a dark, soured vision about the state of the country—and, let’s not forget, misogyny. While the conventional wisdom held that authoritarianism, racial prejudice and ethnocentrism were the main drivers of Trump’s support, my colleague Nick Valentino at the University of Michigan and his collaborators found in forthcoming research that “hostile sexism” was “more powerful than authoritarianism” and “nearly as important as ethnocentrism” as a predictor of support for Trump. This was especially true for men, and “voter anger” multiplied the effects of sexism. The researchers concluded that “sexism is a powerful determinant of voter choice in 2016.”

Yes, Hillary was a flawed candidate. Her penchant for privacy—not surprising given what the Republicans and the national press have put her through since 1992—was her Achilles heel, leading to the use of a private email server that came to symbolize her alleged untrustworthiness. It also led her to be not adroit enough with the media. Hillary misread the country: the fury about the wages of neoliberalism—which, yes, she embodied—that was gripping people, young and old, on the Right and the Left. Thus, she didn’t have a galvanizing progressive message that, as the Sanders campaign demonstrated, millions were hungering for, even some white men feeling they’ve been left behind.

But can we please remember this: In 2015, Hillary Clinton was listed by Gallup, for a record 20th time, as the woman Americans admired most. So we must come to terms with this sad fact, as Penn State professor Terri Vescio put it, “The more female politicians are seen as striving for power, the less they’re trusted and the more moral outrage gets directed at them.” Not all Trump voters are misogynists, but sexism played a role in his victory, as evidenced, in part, by all the Trump regalia calling Hillary a “bitch.”

As Shirley Chisholm insisted more than 40 years ago, “At present, our country needs women’s idealism and determination, perhaps more in politics that anywhere else.” We did not get that this time; indeed, we got the opposite. I still hope, however quixotically, in my or my daughter’s lifetime, that will come to pass. You know all those “national conversations” we’re supposed to have about racism? Can we please add sexism to the list?

Susan J. Douglas is a professor of communications at the University of Michigan and a senior editor at In These Times. She is the author of In Our Prime: How Older Women Are Reinventing the Road Ahead.