Yes, Pensions Are Collapsing, And Progressives Can’t Remain in Denial

Doug Henwood and Liza Featherstone

This piece is a response to Max Sawicky’s critique of the authors’ feature, “Wall Street Isn’t the Answer to the Pension Crisis. Expanding Social Security Is.” Read the original here and Sawicky’s rebuttal here.

Max Sawicky seems to think we’re against generous pension plans. We’re not. He also seems to think that if you just close your eyes and believe hard enough, state and local government pension plans are in good financial shape. They’re not.

Max doesn’t really argue why it’s reasonable to assume that pension funds should return 7 – 8 percent a year over the long term. U.S. stocks have done that in the past, but there’s absolutely no good reason to believe they will in the future. The Congressional Budget Office projects that U.S. GDP will grow an average of 1.8 percent a year over the next decade, the result of 1.3 percent growth in productivity and 0.5 percent growth in the labor force. Why should stocks should grow more than four times as fast as the economy? Were that to happen, after-tax corporate profit would rise from just under 7 percent of GDP today to 12 percent in ten years and 20 percent in 20. We’d run out of money to pay wages, which already seems to be in short supply. Or if that didn’t happen, stock valuations would have to increase from very high by historical standards (where they are now) to astronomical (where they’ve never been).

Maybe the CBO’s projections are wrong. Maybe GDP will grow more like its 1970 – 2007 average of 3.2 percent. You’d still have to explain why stocks should consistently grow at a rate more than twice that of the overall economy, and merely defaming more conservative estimates as University of Chicago-style free-market econonomics isn’t an argument.

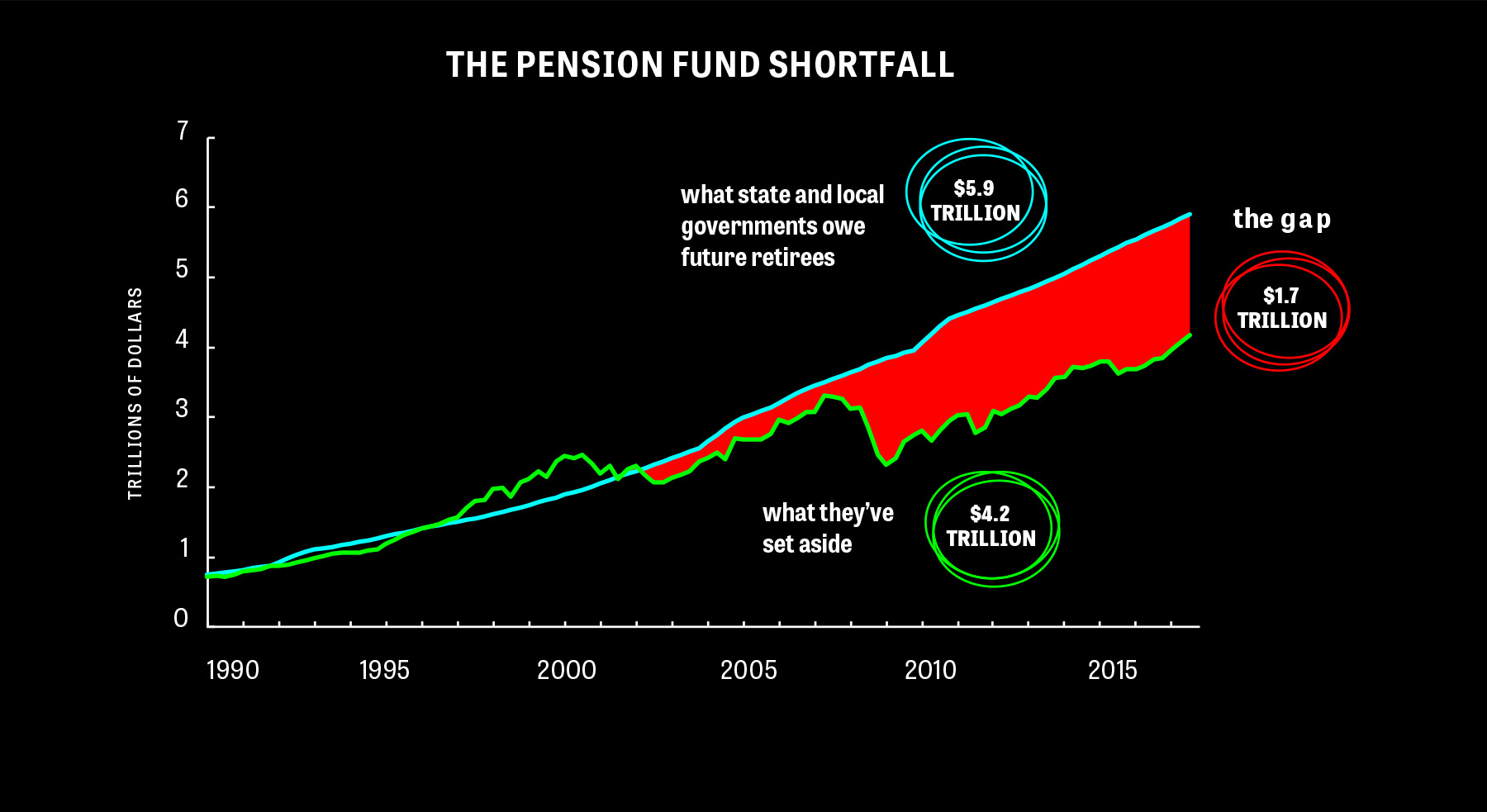

Recent history offers no support for the idea that magical stock market profits — rather than actual contributions — can save the public pension system. Stock prices more than tripled between their low in March 2009 and the end of the third quarter of 2017, but according to Federal Reserve statistics, this great bull market has done little to close the funding shortfall.

That’s because instead of sponsors contributing to the funds, managers have been selling assets since 2009: $291 billion, according to the Fed stats.

Since stock prices are very unlikely to triple over the next decade — that would require consistent annual gains of almost 13 percent, nearly twice the fanciful assumptions that Max shares with complacent pension managers — it’s hard to see how that gap is going to close.

It’s funny Max should bring up the Government Accountability Office (GAO). We looked at a couple of recent GAO reports relevant to the topic and found more worry than he recalls. One, from 2014, contrasts assumptions about the investment returns of private pension funds and public ones. Private funds, which are regulated by the federal government, are required to use the low bond rate; state and local government funds are free to make fanciful assumptions. GAO interviewed a number of experts, some of whom were fine with higher projected returns, but some of whom were worried that assumptions were “too optimistic.” GAO itself finds the use of historical returns statistically problematic; there’s just not a long enough history of long-term stock market performance to speak with mathematical confidence. Nor are historical returns easily applicable to the moving target that is a pension plan: money goes in and goes out at varying rates, making actual performance a completely different animal from a stable stock-market index. Pension plans in Britain, Canada, and the Netherlands all use significantly lower return assumptions, the GAO found, and regulators require underfunded plans to get into shape. No such oversight exists in the U.S.

A 2012 GAO study of state pension funds found increased underfunding, with a growing gap between assets and liabilities. Funds will be able to cover benefits for at least the next decade, but after that, they face “challenges.” And a 2017 report on the state of the country’s retirement system found that “state and local governments may still need to take steps to manage their pension obligations by reducing benefits or increasing contributions.” So we wouldn’t look to Max’s former employer for support.

Math aside, Max doesn’t engage with any of our political points at all — nothing about how the stock market is a mechanism for upward redistribution. One need look no further than the stock market’s reaction to Trump’s election. Skeptical of the erratic billionaire during the campaign, Wall Street came around when it came clear that he’d be delivering some of their favorite things: a rich deregulatory agenda and tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. The market has tacked on 34 percent since his election (though the fat expansion of profits — up 75 percent after taxes — during the Obama years provided a nice foundation to build on). Wage growth and job quality are different stories.

Nor does he engage with the malign work of private equity (PE), which is greatly enabled by public employee pension funds. When you buy a regular stock, you’re almost always buying it from some other stockholder; the company gets no money out of the purchase. When you invest in private equity you’re directly providing money to the PE managers to do their downsizing mischief.

And it’s funny he mentioned Canada. We’ve been talking with Kevin Skerrett, a researcher with the Canadian Union of Public Employees who is the co-editor of a book just out from Cornell University Press, The Contradictions of Pension Fund Capitalism. He takes a line very similar to ours: End private pensions and make them generous and public. (In Britain, local government workers get their pensions from a public, Social Security-like system.) Things are even worse up north in some ways, Skerrett says. Pension funds have been pushing for the privatization of public services so they can invest in the freshly created entity. Recently, a British child care chain owned by the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan’s private equity arm bought a small Canadian child-care chain, prompting fears of the big-boxification of care.

Pension funds are sometimes called “workers’ capital,” which is misleading, since workers have no control over how their funds are spent. The term is especially inaccurate when the funds are used to pursue a directly anti-worker agenda.

Max’s closing lament that “another world is possible, but it is not yet around the corner” is what’s really what’s doing the Right’s work here. You don’t get anywhere in politics by demanding less.