Nations around the world have been meeting for more than two decades to solve the looming problem of climate change. During their most recent gathering — held last November in the Moroccan city of Marrakesh — they intended to iron out some of the glaring issues remaining from the much-lauded 2015 Paris Agreement.

In Paris, countries agreed on a goal to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This is a threshold that scientists generally agree is the point of no return. Yet, shockingly, almost everyone agrees that the Paris accord — even if completely enforced — would fail to achieve that goal.

The arrogance problem

There’s an even more basic problem, though, which arises from our general arrogance about the planet itself. That arrogances lies in our assumption that we have all of the information that we need to make accurate predictions about the earth’s inherently complex climate systems.

What’s becoming clear, however, is that we barely understand how these systems work; and furthermore, that there are factors at play which now make even the most dismal predictions of climate scientists downright optimistic.

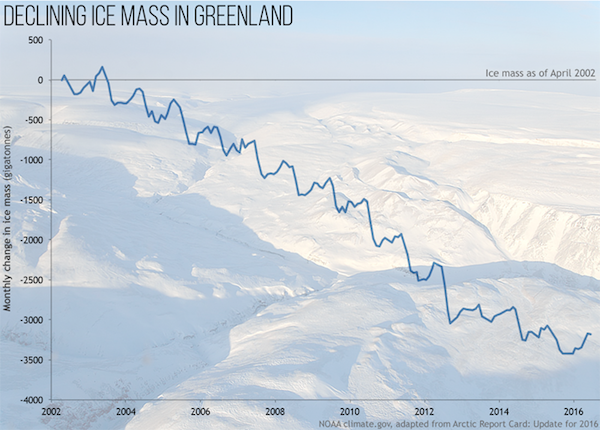

Greenland’s ice sheet is a good example. Climate scientists predicted a certain amount of melting and decay of the sheet, but those predictions are proving to be far wide of the mark. The death spiral of the ice sheet has accelerated in ways that scientists simply couldn’t predict.

As it has since 2002, the Greenland ice sheet continued to lose mass in 2016. (Infographic: noaa.gov)

So, first, we have a global climate agreement that won’t stop the huge impacts of global warming. And second, there’s a very high likelihood that even the Paris Agreement, such as it is, is based on models that we erroneously believe are correct.

Some scientists predict that the melting of the Greenland ice sheet alone could produce four feet of ocean rise. That’s enough to put big chunks of coastline around the world underwater.

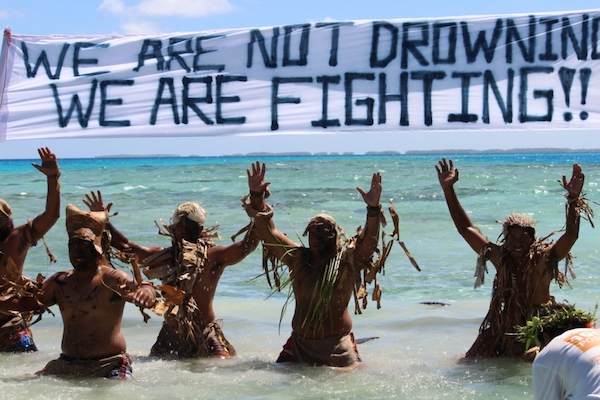

Yet we don’t have to wait to see the impact of global climate change. Small island nations have already become the front line. The governments of Palau, Kiribati, Fiji, and the Maldives are working to buy land in other countries to relocate their residents. Rather than just a truth that is “inconvenient,” these nations face the prospect of being wiped completely from the world map.

Rising sealevels are overtaking the Pacific Island nation of Kiribati. They aren’t alone. (Photo: 350.org)

One would think that such a cognitive dissonance — island nations who contributed the least to global warming are the ones being driven to extinction by those who contributed the most — would lead to real push-back by the people most affected. But while those nations have been vocal advocates for global action at international climate change gatherings, they have failed to take more confrontational actions against the nations that are now killing them off. Part of the reason is their dependence on foreign aid from the very nations that are causing their demise, and the sad legacy of colonialism that has left deep financial ties between the island nations and their former colonizers.

It’s a surreal moment: Individuals and nation-states would generally employ the normal rules of fault and liability to deal with these harms. Yet those rules — seem to be suspended. And nature and ecosystems have generally been forgotten in the mix.

The right to climate

In 2010, a small group of lawyers began working with governmental officials in the Maldives to propose another course. Small island nations would have gone on the offense, using their legislatures and governments to hold other national governments and corporations accountable for climate change impacts. For the first time, these island nations would have sought not only direct compensation from those actors for past and current harms, but court orders stopping climate-change-causing emissions.

While not supplanting international agreements like the Paris accord, advocates of this work would create a different path. They would rely on traditional rules of liability, compensation, and injunctive relief to stop ongoing harm. They would operate parallel to those carrying out the implementation of global agreements, hedging bets on which path can stop island nations from disappearing into the sea.

In 2009, Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed signs a declaration calling for a global reduction in carbon emissions during the first underwater cabinet meeting in the Maldives. (Photo / caption: www1.rfi.fr)

This small group of lawyers and government officials in Maldives developed a framework that would codify a “right to climate” for the people of those islands and the islands themselves, within either national legislation or new constitutional amendments.

Indeed, the “right to climate” is not a new right, but an ancient one. It is the right to have conditions conducive to life, and the right to self-determination and survival. A federal judge in the United States recently recognized that such a right is central to bedrock guarantees of life and liberty.

Accountability: jurisdiction and compensatory damages

Precisely because industrialized and industrializing nations around the world have violated those rights by past and continued emissions, the actors responsible for those emissions must be held directly accountable. Nation-states and residents would enforce those rights. They would file lawsuits within island nation courts against energy corporations and national governments that have taken little action to ensure their emissions do not cause global harm.

Determining which actors are most responsible for the sinking of island nations wouldn’t require new math. Part of the Paris accord requires the compilation of data on emitters in all national signatories. Much of that information is already commonly available. It is therefore possible, for instance, to say that Duke Energy — a utility corporation operating in the United States — is partially responsible, to a certain percentage, for the fate of the people of Kiribati.

Because the harm from those emissions is inflicted directly on the people and ecosystems of island nations, domestic courts within those nations would have jurisdiction over those lawsuits. Lawsuits would seek both compensatory damages — for past, current, and future harm — as well as injunctive relief ordering corporations and governments to cease harming the people and ecosystems of those island nations.

Corporations and governments most likely lack any assets within the island nations that could be taken to satisfy an award. Therefore, successful plaintiffs would present both those awards and court orders to the courts of other nations for enforcement. Ironically, it is corporations themselves that have pioneered the very multinational system of debt liability that would make such enforcement possible.

At the very least, those judgments would begin to establish a clear and legal cause-and-effect that has been largely absent from the world stage. Even if those judgments were blocked from collection for one reason or another, they would begin to force action in ways that the genial, place-at-the-table global climate accords have been unable or unwilling to force.

Regulating harm, legalizes harm

The sheer immensity of the impacts of global warming forces us to recognize that humans on this planet do, indeed, have the power to bring the earth’s complex web of life crashing to the ground. Not only is this bad for all other living beings on the planet, but our collective actions also place the very survival of the human race in the balance.

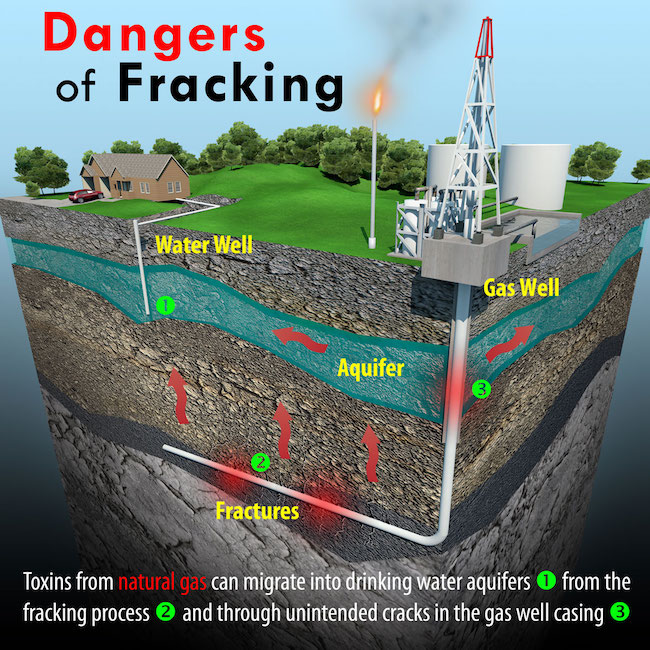

Up until now, the law and governments of industrialized nations have attempted to provide protection for the planet through a system of environmental regulations, which have come up short. Those regulations are often drafted by the very corporations ostensibly regulated by them. They most often serve to legalize industrial practices, such as fracking for oil and gas. These practices cause severe harm to the environment (including global warming pollution).

The dangers of fracking. (Infographic: celdf.org)

While indigenous nations have long seen nature as something other than a “thing” that can be bought and sold, Western systems of law continue to classify nature and ecosystems as merely property. Because of that, the more nature that can be owned, the more can be legally destroyed by the owner.

The community rights movement

That’s starting to change in the United States. Over the past fifteen years, three dozen municipal governments across the country have adopted local laws recognizing that natural communities and ecosystems have a right to exist and flourish. Part of a movement toward “community rights,” these communities have determined that the survival of ecosystems in their municipalities is so intertwined with their own well-being, that nature must be protected by the highest protections available within the law.

In 2008, the people of Ecuador blazed an international path toward the “rights of nature” by including recognition of ecosystem rights within their national constitution. Since then, residents have brought enforcement cases under those provisions. They have succeeded in judicial recognition of the constitutional rights of rivers and other natural communities in Ecuador.

While scientists and climate negotiators mostly speak in terms of human impacts, we must begin to see the planet and its atmosphere as an ecosystem unto itself, worthy of being accorded the highest rights-protections. Thus, not only are some communities working to adopt a human “right to climate” as part of their laws, but many are also working to adopt a “right of the climate” — the right of the planet’s ecosystem to be healthy and unaffected by human-caused global warming emissions. This is a recognition that the climate itself, as an integral function of planet earth, must be recognized as having rights of its own; rights that we are duty-bound to protect and enforce.

If we fail to use this pivotal moment to transcend our 18th century governing systems, which generally ignore nature and ecosystems, then over the next several decades small islands nations will see their very countries underwater. If we do not evolve toward a system of law and governance that incorporates an indigenous understanding of nature, then over the next several decades we could suffer a thousand more climate conferences and it won’t make a bit of difference.

There is a different path, one that communities in the United States and activists in other nations are pioneering. They’re moving forward with the understanding that the change that is needed won’t immediately be embraced at the international level. Rather, it will require first making change at home, where it is possible to do so now, in our own communities.

“Earth” by Kevin Gill. (Photo: Flickr / Creative Commons)

(”Community Rights Paper #15 — Stopping Climate Change: The Slow Train to Nowhere” was originally published on the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) website and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the author. For further reading on the community rights movement, check out a copy of We the People: Stories from the Community Rights Movement in the United States by Thomas Linzey and Anneke Campbell.)