Editor’s note of January 27: On January 26, the day after this story was posted, the FBI reported that one of the people occupying the Malheur Wildlife Refuge was shot and killed by law enforcement following a traffic stop outside of Burns, Ore., during which Ammon Bundy, his brother Ryan and three other individuals associated with the occupation were arrested. The man killed was LaVoy Finicum, a rancher from northern Arizona who is pictured and referenced below. Two other people were arrested later in Burns, one of whom was Pete Santilli, a YouTube blogger from Cinncinati who is also quoted below. An eighth person turned themselves in in Peoria, Ariz. All eight of those in custody face federal felony charges of conspiracy to impede officers of the United States from discharging their official duties through the use of force, intimidation or threats. The refuge is still being occupied by militia members, though the protestors report that there are no longer any children at the facility. Throughout the night David Fry, quoted below, released intermittent livestreams on YouTube reporting on what he referred to as the group’s “final stand.”

What follows is the story I reported from the occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge before this all went down:

On the night of January 10, I pull into the Burns High School parking lot. It’s icy, overfilled with double-parked trucks, media vans and law enforcement vehicles. Inside, bundled up residents of Harney County, Ore., have gathered on the bleachers of the gymnasium. Thirty miles to the east, on the Malheur Wildlife Refuge, an armed group calling themselves Citizens for Constitutional Freedom continues their occupation of the federal land they seized 8 nights prior, making international headlines.

That day, classes in Burns, a high desert town of 2,800, had resumed for the first time since news of the standoff broke. Schools had been closed for a week due to security concerns and this was the second such community meeting — a chance for on-edge residents to get updates, hear from their elected officials, and publically express their views and fears.

Inside the brightly lit gym — jam packed with townspeople, reporters and cops in full tactical gear — a microphone was being passed to those who wished to speak. A middle-aged man in a baseball cap had the floor and was explaining that, while he thinks the Bundys should go home for their own safety, and does not condone their actions in any way, he sympathizes with their frustration over what he sees as decades of economically disastrous environmental policies wrought by an overbearing, out-of-touch federal government.

He tells the audience, “The other night, after the first meeting, I went home and at 2 in the morning I woke up — I could not turn my brain off.” He explains he decided to get on his computer and write a poem — a poem he’d like to share. After asking everybody to bear with him, and a reminder that he’s not a professional poet, he begins reading:

Environmentalists, oh the environmentalists — they think they know it all.

Most of which live in the city, in those buildings big and tall.

They breathe the thick dark air and live in nasty smog,

Then try to tell us how to live our lives as they sit and write their blogs.

They call us rednecks, hicks, clinging to our guns and religion, and they think it’s really funny,

But we all know they don’t really care about our lands, as they catch all that liberal money.

Our local federal agencies, with whom we work and know we can rely,

Many of which grew up here — farmers, loggers and ranchers themselves — are just trying to get by.

It’s the ones who make the policies in D.C. — the one’s we call the Feds,

They wave their ink filled wands, without the facts, like a snake with many heads.…

It’s time we make a stand, get educated and come up with a solution.

We have a map, it’s already laid out for us, it’s called the Constitution. …

Most of this entire country on the map is mostly red,

Except for a few costal states, whom without us might not get fed.

He pauses to make sure the audience knows his remarks are not directed at local Bureau of Land Management (BLM) employees, many of whom he “loves,” but rather at the bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. With palpable emotion, his address to politicians crescendos:

It’s high time you add our farmers, loggers and ranchers to your list of endangered species!

The crowded gymnasium erupts with applause, as if Burns High had just scored a basket.

The consensus of the townspeople was clear: The Bundys need to leave now, before they get shot. But when it comes to speaking out against federal land management policies, we understand why they’re angry. This appeared to counter much of what had been reported in the news. Person after person stood up to the microphone to encourage the Bundys to leave, often vehemently denouncing their methods as way-too-radical, but then went on to express some sympathy or gratitude (or both) for the occupation’s overall premise.

Harney County residents gather in the Burns High School gymnasium to discuss the occupation. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

A meeting at the gate

Earlier that evening, I was sitting around a campfire with three protestors tasked with guarding the main entrance to the refuge. The sun was setting, it was 19 degrees and other members of the media had left for the day.

The man in charge of the post was a well-spoken and philosophical guy who had no trouble articulating why he didn’t recognize the federal government. He’d definitely read the Constitution, and somewhere along the way interpreted it to mean that when it came to the refuge, or any public land for that matter, the government had no more authority than “a Macy’s mall-cop.”

As I listened, trying to follow his line of reasoning, I couldn’t help imagining the whole thing going south for these guys — helicopters, drones, a coordinated assault. It reminded me of a Jack Reacher book.

One member of the group was 20-something, lacking the intellectual horsepower of his buddy and I guessed, fairly or not, a passenger on the bandwagon. His fiancé had broken up with him after seeing an Idaho news broadcast that called the refuge occupiers terrorists. This really bummed him out. He said he missed drinking beer (prohibited on the compound) and fishing but, whether he understood the particulars or not, remained sold on the cause. His job was to occasionally move the truck parked perpendicularly across the driveway, blocking vehicular access to the occupied structures below. (The dozen or so seized structures, with exception of the watchtower, were a ways down a long driveway and not visible from the entrance.) This was something he could only do if he received an “OK-copy-roger” over his handheld radio.

Sillhouettes could be seen in the Malheur Wildlife watchtower. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

Another reminded me of a guy I did roofing jobs with in Northern Wisconsin — loveable when you got to know him but perhaps prone to making terrible decisions with firearms. And that’s what struck me as more than a little spooky about the situation. “We’re ready to die if we have to,” I heard over and over again. For what, again? I thought.

Occasionally a pickup truck would pull up from out of state and guys in cowboy hats would get out to take pictures next to the entrance sign, sometimes with their families in tow. Others dropped off food. Having seen Stephen Colbert’s Oreo sketch, I asked how they were doing on the calorie front and one of the guys took his phone out to show me a photo of all the supplies they’d stashed since the media reported they forgot to bring any. “We have enough for months,” he said. It did look like a lot. (In addition to care packages, the Citizens for Constitutional Freedom have received parcels containing sex toys, tampons and your run-of-the-mill hate mail.)

A man stops by the Malheur Wildlife Refuge to have his picture taken. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These TImes)

Twice a four-wheeler came up from the refuge carrying a replacement guard and fresh batteries for the walkie-talkies. (The militia has commandeered all of the facility’s trucks and earthmoving equipment. The BLM, not anticipating a hostile takeover, left keys in the ignitions.) I was told I couldn’t enter the refuge that night, but to come back in the morning.

Before leaving, I found myself wondering how this situation they’d created could end well and decided there was wisdom in the federal government’s decision to keep the occupation a “local law enforcement matter” and let it play out. The town was crawling with FBI agents. I wondered if they had someone inside.

Scotty Wills, from Idaho, is a member of the Three Percenters (3%ers) — a paramilitary patriot movement founded in 2008 to prevent the “overreach of the federal government.” (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

The Hammonds and Bundys

Cliven Bundy, Nevada rancher and father of 14, became a household anti-federalist name in 2014, but his trouble with the government goes back decades. In 1993, the BLM determined that hundreds of thousands of acres in southern Nevada needed to be protected from grazing in order to save the desert tortoise. To protest this move, Bundy refused to pay the government for his grazing permits on federal land — $1.35 per animal unit month (AUM) ($16.20 per head annually) in Western states — while continuing to use it.

In March 2014, federal agents responded to the dispute by seizing some of Bundy’s cattle. This culminated in a larger standoff in which hundreds of protesters and an armed militia converged in Bunkerville, Nev., demanding the government back down and return the cattle.

Anxious not to trigger another Waco, the government did back down and, as far as they’re concerned, Cliven Bundy still owes them in excess of $1 million. Widely hailed as a patriot by conservative pundits in the standoff’s early days, support tapered off when a video surfaced in which Bundy speculated that black people (who he referred to as “the Negro”) were better off as slaves than they are today receiving government assistance.

There are 800,000 ranchers and cattle producers in the United States but two of Cliven Bundy’s sons, Ammon and Ryan, are leading the occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge. Ammon, 41, owner of an auto repair business outside Phoenix, Ariz. and his older brother Ryan (of Utah), arrived in Harney County on January 2 to take part in a rally organized to protest the re-incarceration of Dwight and Steven Hammond — father and son Oregon ranchers.

In 1964, Dwight Hammond Jr., 74, and his wife Susan purchased 6,000 acres in Harney County. Today, Hammond Ranches, Inc. owns and runs cattle on over 12,000 acres. Until recently, the Hammond’s operation also included summer grazing permits on 26,000 acres of adjacent public land. This changed in 2012 when, despite the family’s prominent status in the community, Hammond and his son Steven, 46, were found guilty of setting illegal fires on those public lands. Their grazing permits have been denied ever since.

The arson charges stemmed from two separate incidences in 2001 and 2006 — the Hardie-Hammond Fire and Krumbo Butte Fire (respectively) — and accounts of what happened (and why) vary greatly depending on who you talk to. The Hammond’s maintained throughout the trial that the earlier fire, which ultimately burned 139 acres of BLM controlled land, was set in an effort to clear a portion of Hammond land of invasive western juniper trees so their cattle could graze. The practice is not uncommon in ranching but this blaze got out of hand and spread onto public land. The prosecution, however, alleged that the fire was in fact an attempt to cover up an illegal deer hunt. The 2006 fire, the Hammond’s said, was a controlled back blaze started to protect their winter feed from an approaching wild fire. In this case, the prosecution insisted Hammond was aware of the countywide fire ban that was in place at the time and put the lives of young firefighters in the area at risk.

Ryan Bundy (right) takes a walk around the refuge. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

Why the protest?

The jury found them guilty, but this is not the crux of the dispute. Due to the federal nature of the arson charges against them, the Hammond’s faced sentencing under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). Signed into law by President Bill Clinton following the bombings of the World Trade Center garage and Oklahoma City federal building, the act mandates a minimum five-year sentence for crimes that apply. Though convicted under the AEDPA, at sentencing the Hammond’s council successfully persuaded then District Judge Michael Hogan that this punishment was too severe — insisting it did not fit the crime and was “unconstitutional.” Hogan agreed, saying:

“These people have been a salt in their community and liked, and I appreciate that…I am not going to apply the mandatory minimum…to do so under the Eighth Amendment would result in a sentence which is grossly disproportionate to the severity of the offenses here. And with regard to the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, this sort of conduct could not have been conduct intended under that statute.”

Sparing the old man what many Hammond supporters called a “death sentence,” Dwight was sentenced to three months while Steven received one year for his role in the earlier fire. The Hammonds were further ordered to pay the BLM $400,000. They served this time, paid the money and were released in 2013 and 2014. But the ordeal was far from over.

Doubting that Judge Hogan had the authority to reduce a mandatory sentence, then U.S. Attorney for the state of Oregon Amanda Marshall along with federal prosecutor Frank Papagni challenged the ruling and, in 2014, persuaded the Ninth Court of Appeals to review, and ultimately dismiss, the District Court’s leniency. Last October, after the Supreme Court rejected the Hammonds’ petitions for certiorari, Chief Judge Ann Aiken ordered both men back to prison to complete the five-year sentence mandated by the AEDPA, minus time already served.

Acting U.S. Attorney Billy Williams said about the ruling, “Congress sought to ensure that anyone who maliciously damages United States’ property by fire will serve at least 5 years in prison. These sentences are intended to be long enough to deter those like the Hammonds who disregard the law and place fire fighters and others in jeopardy.”

That did it. On January 2, supporters of the Hammonds, infuriated that the two prominent ranchers had been tried as terrorists, staged a demonstration in the town of Burns to protest the federal court’s decision. (The Hammonds had been allowed to stay home for the holidays but were ordered to report to federal prison in San Pedro, Calif., the following Monday, January 4, which they did.) After the planned rally in Burns, a faction of demonstrators led by Ammon and Ryan Bundy split from the larger group and headed in a convoy of trucks to seize the refuge, then unoccupied. Though a surprise to many, the escalation was not spontaneous.

In a Facebook post denouncing the local sheriff and federal government’s treatment of the Hammonds — something he viewed as a tyrannical abuse of power worthy of drastic action — Ammon Bundy urged “patriots to stand up” and “come prepared” to the refuge. He added, “This is not a decision we’ve made at the last minute.”

How much land does the federal government own (and why)?

Western range wars are not a new development. The federal government began its foray into the administration of non-state acreage in 1803, when it acquired 530,000,000 in the Louisiana Purchase. (Prior to that, federal “land management” had consisted mostly of exterminating Native people east of the Mississippi.) The notion of permanent federal land ownership, however, did not take hold until the early 20th century.

Ironically, it was the perceived need of the federal government to mediate disputes between homesteaders, ranchers, loggers, miners and Native people — to settle land, water and grazing conflicts among groups competing for the same resources — that led many ranchers to support federal ownership in the first place. But as the west’s population and economy surged, it also became apparent regulations would be needed to prevent the complete destruction of shared habitat by competing independent interests — the “tragedy of the commons.”

Today, the federal government does own 640 million acres (or 28 percent of land in the United States) and nearly half of this land is in 11 western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming). The task of administration is primarily divided among four agencies: the BLM, the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the National Park Service (NPS) and the Forest Service (FS) — all of which are overseen by the Department of the Interior (DOI) except for the FS which falls under Department of Agriculture (USDA) jurisdiction.

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt designated what later became the Malheur Wildlife Refuge as an Indian reservation and bird sanctuary. At the time, hunters had all but decimated North American bird populations in their pursuit of feathers — plumage to sustain the booming lady’s hat industry. Many species recovered and eastern Oregon provides critical habitat and nesting grounds for hundreds of species of migratory birds. Over time, the FWS has expanded the amount of land it protects in Harney County, often buying out ranchers in the process. The Malheur Wildlife Refuge is one small part of what some rural people view as a larger Western problem.

Before the reduction in public land available for grazing, eastern Oregon’s timber industry saw an even greater rise and fall. As recently as 1973, thanks to industrial saw mill operations, Harney County was the wealthiest county in the state by per capita income. This changed when the Hines mill, the last of the major players, closed in the early 1980s. At the time, company president Howell Howard attributed their inability to turn a profit on dwindling access to government-owned forests, adding: “This timber shortage is being made more acute by environmentalists’ demands for more wilderness areas and by the failures of Congress to provide funds and manpower to the Forest Service so that agency can manage the forests for the highest yields.”

Decades later, the blame has not shifted. Harney County now ranks among the state’s poorest, with a median family income of less than $37,000, and the people I heard speak lament the federal government’s environmental agenda — something they likened to an oppressive force, guilty of systematically destroying their livelihoods. They spoke of the campaign to get the spotted owl on the endangered species list in the 1990s and how, more recently, efforts to protect the greater sage grouse had resulted in what they view as one federal land grab after another. These efforts, aimed at conservation, did restrict land use.

They see the government, malevolently aligned with a condescending liberal media, as hopelessly out-of-touch with their day-to-day lives and the out-of-towner Bundys know exactly what to say to capitalize on this frustration. “Their lands and their resources have been taken from them — to the point where it’s putting them literally in poverty,” said Ammon Bundy. “And this facility here [the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge headquarters] has been a tool into doing that. It is the people’s facility, owned by the people. And it has been provided for us to be able to come together and unite, and making a hard stand against this overreach, this taking of the people’s land and resources.”

Back to the refuge

I returned the following morning hoping to get inside. New faces were milling around the campfire, still burning. I was told I was early — that the day’s press briefing wouldn’t start for two hours — but was welcome to keep warm around the fire and record what was said (something I’d been told not to do the evening before). A man named Darrow Burke, 57, was splitting wood. Asking where the logs came from, I was told a family from Burns had delivered them with the promise of more if needed. “The love here is more than you’d find at church,” somebody said.

Darrow Burke, of Ukiah, Cali., chopping firewood. He would overturn his van on the icy road into town a few days later but was uninjured and not arrested. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

Also sitting near the fire was a man in a wheelchair — a double amputee wearing a ‘Bye Felicia’ T-shirt, holding a worn out bible as he told profanity-laced stories about all the times he almost died — a frequent occurrence I soon learned. He invited me to sit down next to him and introduced himself as James Ranger Stanton, BMCS Master Diver, Ret. from Ft. Sumner, N.M. He explained he’d been sitting at home when he saw a TV news broadcast out of Albuquerque that referred to those at the refuge as “terrorists.” This pissed the Navy veteran of 20 years off so much that he put on his legs, told his wife not to worry, and drove himself all the way to Burns. Not directly affiliated with the various militias (I counted four different ones — the Citizens for Constitutional Freedom, Oath Keepers, 3 Percenters of Idaho and the Pacific Patriot Network), Stanton was there to show his support. We ended up talking for the better part of an hour. He said he didn’t always believe in God but that a lifetime of “seeking truth” changed that. There were two kinds of people in the world — the decent kind and “no good sons of bitches.” Politicians drive him crazy. President Obama? Not a fan. Donald Trump? He wipes his ass with toilet paper depicting the billionaire on every sheet. But Ben Carson he likes — Stanton thinks he can save the country.

James Ranger Stanton, from Ft. Sumner N.M., is a retired U.S. Navy veteran. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

“I’m here to do the best I can to serve my fellow man in a last ditch effort to save freedom for my kids and grandkids,” he says. “And tell Obama I am willing and ready to go to prison for clemency for the Hammonds. I am sick of this injustice.”

A man on horseback approaches from the refuge carrying an American flag. Another reporter tells me it’s Duane Ehmer and that this ride has become a daily ritual. I ask her how to spell “Ehmer” and she says, “I don’t know, but check the New York Times from yesterday.”

Ehmer says he owns a welding shop in Irrigon, Ore., adding, “but then I’m a part-time cowboy on top of that because you have to have more than one job around here or you’ll starve to death.” An awkward silence follows and I ask the only question I can think of: “What did you guys have for dinner last night?” “Meatloaf,” he says.

Duane Ehmer and his horse, Hellboy, walk around the Malheur Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

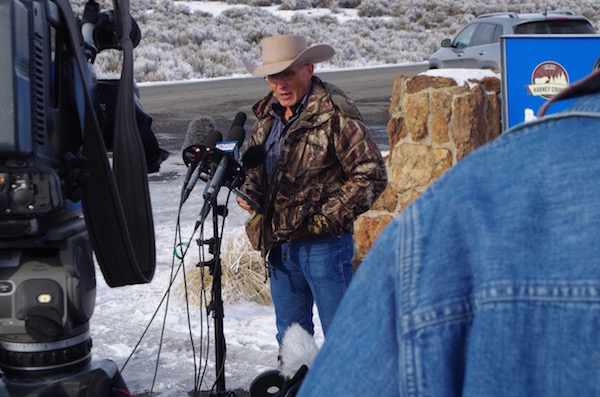

The press briefing convenes in the parking lot and LaVoy Finicum, a rancher from northern Arizona, explains that Ammon Bundy is engaged in a discussion with authorities about a possible end to the standoff that coming Friday (this never happens) and won’t be able to take questions. He reiterates his support of the Hammonds and implores people watching to consider what their freedom means to them. Then he cedes the microphones to Joseph Santoro, a Colorado representative from the Pacific Patriot Network (PPN) who’s recently arrived to offer the organization’s services as mediator between law enforcement, the F.B.I. and the Bundy’s “in the event they are needed.” The briefing concludes with a progressively unhinged prayer from Stanton, imploring America to “wake up” and “stand with us” (having no legs, he gets out of his wheelchair and props himself up on the ground). He screams something I didn’t understand and a small group of people say, “Amen.”

LaVoy Finicum, a rancher from northern Arizona, addresses the media. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These TImes)

After what seemed like (and was) hours, Ehmer invited members of the press down for a tour of the refuge. I followed behind his horse and American flag, flanked by an independent film crew, a local reporter and Pete Santilli, a rightwing YouTube journalist who was nothing short of thrilled to be covering this “Constitutional crisis.”

As buildings came into view, there were more than I’d expected. The driveways and walkways between the dozen or so structures had been plowed or shoveled which must have taken some time. What else did they have to do? And I saw more cars and trucks than I did people before being led to a building containing old lumber and machine parts — a storage shed. Here, our guide who’s name I didn’t catch, alternated between pointing out haphazardly stored equipment and looking into the cameras in hopes of compelling anybody watching to be as disgusted as he was at “how the government treats our property.”

Jason Patrick, from Georgia, quit an $80,000 a year roofing job to join the occupation. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These TImes)

This theme was taken a step further as we walked over to a much larger structure — a long garage with its doors rolled opened — that was in the process of being swept, scrubbed and washed clean by a dozen protestors wearing OSHA approved respirators. A trailer was parked out front and getting loaded with whatever the participants determined was junk. Asked what they were doing, Jason Patrick, an avid follower of Constitutional causes, explained they were doing what the BLM had failed to do and were working to leave the refuge “better than they found it.”

Occupiers clean out BLM buildings at the Malheur Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These TImes)

In the distance I could see a skid-steer trudging along in the snow and was told they’d been removing a stretch of BLM fencing to open up land for an adjacent rancher.

The anti-federalist-militia-hoping-to-spark-a-revolution angle of the story was begining to look like a group of people voluntarily subjecting themselves to unpaid manual labor in a remote part of the Oregon wilderness in January. My feet were getting cold and I decided to start back up the driveway to the entrance. On the way, I stopped to talk to a young man who was standing next to his car.

David Fry, 27, explained that, despite being on probation for a marijuana offense, he felt it was important to drive to the refuge from Ohio.

“We all live on this earth. If we trash our own house, that’s terrible,” says Fry. “We’ve got this gas leak in California — it’s like the biggest ever recorded. You’ve got Fukushima just dumping radiation into the Pacific Ocean. All these problems are happening. How long do we have to just keep letting things go? Before our house becomes uninhabitable?”

I mentioned that many people don’t associate this occupation with environmental awareness.

“We’re here to take a stand against the government,” says Fry. “I support the Hammonds, who were tried as terrorists for something so small. We’re coming here to organize. We as Americans need to stand united because divided we fall.”

Fry came across as lucid, but a closer look at his social media history revealed video rants about “Zionist Jews,” 9/11 being an inside job and calls for Obama to be executed for treason — comments Fry, with his new found status as IT guy for the militia movement, insists were taken out of context.

Fry, 27, posing in front of the car he drove from Ohio to participate in the occupation. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These TImes)

WTF?

I’d driven 450 miles to get to Burns, which gave me 450 miles of windshield time on the drive back to hash out what I’d seen. I turned on the heat and found an FM tribute to David Bowie. Had the Bundys heard he died yesterday? Should I have said something?

I stopped for lunch at the only restaurant on the 100-mile stretch of highway out of town and became the only customer in a family run place — father behind the counter and his son in the kitchen. He asked where I was coming from. “Burns,” I said. “Well, I’ll tell you this,” he said, “the Hammonds are good people — they’d come in here all the time.” He went back to reading his newspaper, I ate and got back in the car.

Was the standoff really about the Hammonds? Or were the Bundys seizing an opportunity to incite already frustrated people? This isn’t hard to do these days, but I doubt cattle ranching will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Constitutional or not, BLM grazing fees are 93 percent less expensive than their private counterparts. The privatization of public land, in fact, presents enormous potential financial downsides to those currently using public land for private profit — ultimately a privilege, not a right. Perhaps there are better ways to manage them but federal lands are held in trust for all Americans, not just for the benefit of those who live near them.

The occupation aside, Burns is a community wrestling with the question of local control. People are struggling to support themselves. But is this because of an oppressive government or because the nature of what’s valuable is fundamentally changing? Technology and globalization — powerful forces — are in the process of altering what, where and when work is valued. Understanding this doesn’t make bills any easier to pay right now but, if we’re going to adapt, it’s important to acknowledge what no longer works so that we can ultimately find out what will.

In the pursuit of regional prosperity each community’s priorities will vary, but the desire for a sustainable economy is inherent to all of them. What about trusting the people with an actual stake in their community — skin in the game — to manage their best interests? There is a need to protect sensitive habitats that would otherwise be exploited by roving corporate nomads. But if the federal government is going to cling to credibility on this matter, it should stop passing sweeping protections that disproportionately affect individuals while green-lighting massive industrial projects that benefit a corporate few. That just ticks people off.

I compared what I saw in Burns to what I read about it in the news. Was the media playing a role that was productive, or reductive? These days every crisis gets turned into a lens for cultural projection. I’d seen the different ways the standoff was getting leveraged around the Internet in the context of other people’s frustrations and some worked better than others.

It wouldn’t be tough to argue, for example, that had the occupiers not been white they’d be dead or in jail by now. That one tracked. And the irony that a group of white men waving American flags, upset that the federal government had stolen their land and was destroying their way of life was not lost on the Burns Paiute Tribe.

“The tribe supports the prosecution of the occupying individuals. Under terms of the Burns Paiute Tribe’s treaty with the United States, the government guaranteed it would protect the safety and property of the Northern Paiute people,” wrote tribal chair Charlotte Rodrique in a message to the FWS.

But then there were those rallying to online comment sections — America’s panic room — to make some variation on the claim “these terrorists should be carpet bombed because they’re no better than ISIS.” And that one doesn’t track for me. There’s a right and wrong way to go about being angry, and these protestors selected the latter — but they’re not terrorists. They consider themselves Paul Reveres, warning the rest of us of impending tyranny. They don’t want to kill anyone.

Lodged deep in the extreme conservative mindset is a powerful compulsion to “go back.” In this case, back to a time when more people cut down trees (and there were more to cut down); back to when more people spent their days on horseback with a gun at their side to hunt food; back to when extracting resources from big holes in the ground could sustain a town for generations; and back to when you could burn what you wanted and it would all blow away. This is more than an exercise in nostalgia. For more than 200 years, this brand of interaction with the natural world (and massive government investment) helped create the prosperity that brought us to where we are today. It worked! Forget for a moment that this probably isn’t a recipe for success in the 21st century.

Rather than demonizing this perspective, we could try to understand that fantasizing about a past and projecting that onto the present offers something increasingly hard for many American’s to find: a sense of security. In other words, looking back fondly isn’t crazy. It’s cozy. Add to that a growing populist sentiment that the government-as-we-know-it is incapable of delivering on what it promises — the now ubiquitous notion that we are being helmed by a political class with a knack for acknowledging problems then somehow finding expensive ways to make them persist (drugs, poverty, Middle Eastern dictators and unaffordable health insurance, etc.) — you’re going to see legions of people desperate for something familiar whether or not it’s practical, legal or sane.

Half-way through the Mt. Hood pass, the President’s final State of the Union Address came on Oregon Public Radio. An odd juxtaposition to two days spent scoping out an anti-federalist movement, but appropriate. I wanted a pair of the President’s rose-colored glasses. Whether Biden finds a cure for cancer or not, it was nice to hear some optimism.

Oregon state highway 205. (Photo: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)