The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was born into a broken home. Worse, half of its family has spent years trying to kill it. Now it’s a six-year-old with serious trust issues but, according to a recent report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 90 percent of Americans now have health insurance. For the first time ever, fewer than one in 10 people are uninsured.

After that the good news gets harder to find. When it comes to the latest assessments of health care in the United States — in terms of whether or not people have reliable access to hospitals and appointments they can afford — there’s more than just anecdotal evidence from the ACA’s diehard opponents to suggest cause for both short and long-term concern. In many rural counties, due to a range of contributing factors — including a shortage of doctors, a sicker-than-anticipated population, lack of competition in the marketplace, the closing of hospitals and a raging opioid crisis — the outlook is grim.

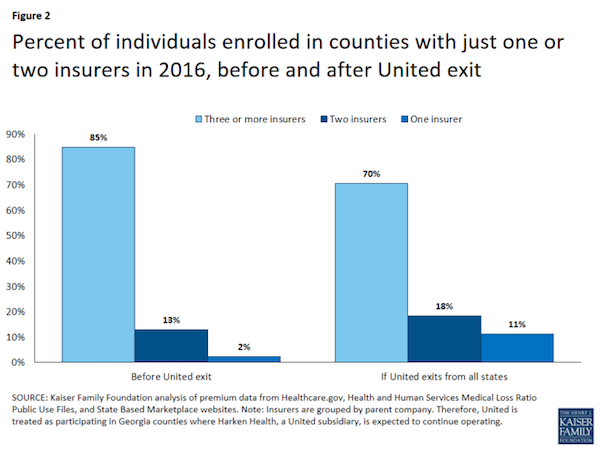

This week, citing a $475 million loss in 2015, and an estimated $500 million loss this year, UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest health insurer, announced that in 2017 it would be dropping out of “all but a handful” of the ACA’s state exchanges. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), which monitors the exchanges, points out that this wasn’t entirely unexpected. In their state-by-state analysis of the projected fallout from UnitedHealth’s departure, they note the company had been “cautious about entering the ACA marketplaces” from the start, “only participating in a handful of states in 2014 before expanding its reach in 2015 and 2016.” But they aren’t alone.

Other insurance providers have abandoned their less profitable rural exchanges. Meanwhile more than half of the ACA’s Community-Oriented and Operated Programs (CO-OPs) — the intended not-for-profit alternatives to traditional carriers that were established after Republicans (and some moderate Democrats) succeeded in branding any public option as a tyrannical government “takeover” of healthcare — have failed due to management, enrollment and financial difficulties. By early 2017, the Wall Street Journal reports, it is estimated that in more than 650 counties — 70 percent of which consist of rural populations — only one option for health care coverage will be offered on the ACA exchanges.

The KFF analysis states:

In addition to potentially leaving several areas with one or two participating insurers, a United withdrawal would be most disruptive where a large share of enrollees had been enrolled in one of the company’s plans. … While insurer-level enrollment data are unavailable in most states, we do know from Health and Human Services (HHS) reports that a large share of enrollees tend to enroll in one of the two lowest cost silver plans. … Overall, United offered one of the two lowest cost silver plans in 647 counties in 2016; this represents 35% of the counties in which the company participated and 21% of counties across the U.S. This represents 22% of enrollees living in areas where United participates and 16% of enrollees nationally. If the general trend reported by HHS holds true in these counties, and enrollees were more likely to sign up for the low-cost silver plans, it is likely that United held a sizable share of the market in these areas.

As with any unprecedented undertaking there were bound to be unforeseeable variables, but since the law’s implementation the Obama administration has maintained that competition in the marketplace was a central part of its cost-cutting strategy. Regulators in rural states facing fewer options now fear the trend will lead to a rise in premiums that are already more costly than those who need the insurance can afford. According to Inovalon, the healthcare information and technology firm cited in the WSJ piece, rural exchanges are having trouble realizing a profit for two reasons — people are requiring more care (they’re sicker) than anticipated and the cost of that care is significantly more than it is in urban areas.

Rural hospital closures

Elizabeth Zach is a staff writer for the nonprofit Rural Community Assistance Corporation where she writes about rural poverty and economies. She’s also a 2016 fellow with the Annenberg School of Journalism at the University of Southern California currently researching the spate of rural hospital closures in recent years for a series of stories that will be published later this year.

Spate is not an exaggeration. Since 2010, 73 hospitals in rural America have shut their doors. “That’s essentially one per month in that time period,” says Zach. The Cecil G. Sheps Center For Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, which tracks the status of hospitals nationwide, reports that hospital closures are not a new phenomenon but that closures “have been ticking up since the recession of 2008-2009.” The center’s website explains, “Long-standing trends — such as generally poorer financial performance in the South — may contribute to closure rates.” It goes on to say, “Some observers have noted the potential effect of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) and/or the correlation with a state’s decision of whether to expand Medicaid.”

A map of where rural hospitals have closed since 2010. (Image: http://shepscenter.unc.edu)

Zach says that while many of the closed hospitals are being replaced by rural health care clinics, these are often outpatient facilities that don’t provide emergency or urgent care. This becomes especially troubling in light of the ongoing heroin/opiate abuse crisis that is plaguing many rural communities. Fatal drug overdose is now the leading cause of injury death—an increase of 270 percent between 2010 to 2013. From 1999 to 2013, the number of deaths caused by heroin/opiate-related overdose has increased a staggering 400 percent.

Hospitals are required by law to treat patients in need of emergency care, but Zach says this can drive up costs for rural hospitals already operating on “very thin margins.” Meanwhile fewer hospitals means people have longer drives to the hospital or must rely on costly transport via police and fire departments.

So what most stands in the way of people in rural communities getting the healthcare they need — cost or access? Zach puts it this way:

“The ACA — as good as it basically has been in covering so many more people — has been a double-edged sword for rural hospitals, which are now required to provide (more) care with less funding (many are closing because they have not been reimbursed by the U.S. government for services). In short, I believe the problem is more one of access for rural patients, and not necessarily of cost. For rural hospitals, the economics are simply not in their favor.”

What comes next?

Like these hospitals, millions of Americans are also dealing with economics that are not in their favor. Furthermore, all of us, sooner or later, require medical attention. There’s always been something inherently twisted about basing the quality of the treatment people receive on what they can pay for it, but that’s especially true in an industry known for $2,500 broken arms, $30,000 8-week chemotherapy sessions and market-savvy pharmaceutical executives who appear far more concerned with world-domination than the prolonging of human life.

Ensuring that all Americans have affordable access to the healthcare they need — that they are not one accident away from financial ruin — was the premise on which the ACA was built. The fact that 90 percent of people can now say they’re covered is significant. But if people can’t put those plans into action, or afford the premiums required to keep them, nothing has actually been fixed. Requiring people to participate in a broken system is not a solution. That said, what should be crystal clear to both sides of the aisle by now is that filling the void created by a refusal to negotiate (and the absence of any viable alternatives) with more talk also does nothing to help the people who need it.

The next administration will ultimately decide whether this six-year-old law gets put into therapy, replaced by a single-payer healthcare system for all Americans, or triumphantly repealed and replaced with something so fantastic that you can’t even imagine how good it is going to be.