Trump Nominates a Secretary of Agriculture (and, No, It’s Not Wendell Berry)

John Collins

Filling the last remaining vacancy on his incoming administration’s cabinet, President-elect Donald Trump has nominated former Georgia governor Sonny Perdue for secretary of agriculture. The announcement puts an end to weeks of mounting speculation over who (on Monday, January 23, presumably at around 9:00 a.m.) will be showing up to replace Tom Vilsack as the Department of Agriculture’s new boss. (Vilsack resigned from the post one week early and is reportedly taking his talents to the U.S. Dairy Export Council.)

Once confirmed and sworn in, Perdue will have the unenviable task of navigating a third straight year of declining net farm incomes, pushback from farmers and ranchers on Obama-era environmental regulations, heavily-leveraged family farms struggling to compete, a massive global agribusiness industry hell bent on consolidation and, perhaps most importantly, the drafting of the 2018 farm bill — an omnibus law revisited by Congress every five years that governs myriad aspects of our food supply.

On the human side of the equation, millions of American grocery shoppers increasingly want to know what they’re eating, where it comes from, whether or not it’s been treated with chemicals and/or if it’s been genetically engineered in a laboratory. The world’s largest purveyors of insecticides, herbicides, patented seeds and heavily-processed food would much prefer these details remain a mystery and lobby accordingly. Caught in the middle, most farmers just want to make a decent, reliable living that doesn’t involve jumping through unnecessary hoops for a hyperactive Uncle Sam. Depending on where a secretary of agriculture’s sympathies lie, he (or she) can tip the scales one way or another on a number of important issues.

Here’s what we know about Sonny Perdue:

George Ervin “Sonny” Perdue III, 70, is the son of a farmer and has been involved in some aspect of agriculture for his entire life. In the 1970s, Perdue studied and practiced veterinary medicine prior to starting several agribusinesses. His most recent venture, founded in 2011, is Perdue Partners, LLC. According to this Bloomberg bio, the LLC “operates as a global trading company that facilitates U.S. commerce focusing on the export of U.S. goods and services through trading, partnerships, consulting services and strategic acquisitions.” Depending on your faith in public servants these days, such intimate knowledge of commodity trading is either a good sign of practical business experience or deeply troubling. But Perdue’s international trade credentials, which include opening Georgia’s international trade office in Beijing while Governor, are bound to be a selling point for some.

Perdue got his start in politics as a Democrat and served as a Georgia state senator from 1991 to 2001, but switched parties in 1998. In 2003, he became Georgia’s first Republican governor in 130 years. Under his leadership, Georgia enacted some of the harshest illegal immigration measures in the nation, though he’s since scolded the Republican party for failing to be more inclusive. While in office Perdue was involved in a land scandal that threatened to cost Georgia taxpayers upwards of $30 million but received a good deal more national criticism in 2007 when, during a particularly bad regional drought, he asked Georgians to “pray for rain” on the steps of the Capitol. Perdue, a Baptist and father of four, was also criticized for implementing strict anti-welfare policies that negatively impacted the poor in his state. He is the first cousin of David Perdue, a U.S. Senator, and not affiliated with Perdue Farms — the chicken, turkey and pork processing company based in Maryland.

Positive and negative reactions

Numerous political allies and large farm organizations were quick to praise Trump’s decision. Zippy Duvall, president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, called Sonny Perdue’s nomination “welcome news to the nation’s farmers and ranchers.” At least the new secretary of agriculture is not a Monsanto executive. Last Wednesday, prior to announcing his pick, Trump met with executives from Monsanto and Bayer — two of the world’s five leading biotech companies — to discuss their proposed $66 billion merger. This sent chills down the spines of countless already traumatized political junkies. Perhaps, Americans should take some comfort in the fact Trump ended up selecting someone who actually grew up around farming and is presumably aware of the struggle many farmers face.

That said, there’s no doubt Perdue gives environmentalists — and the sustainable food movement more generally — plenty to worry about. He’s a well-known climate change skeptic and a disciple of big agriculture. In an article sizing up Trump’s potential picks for the position and their stance on the issues, Organic Consumers Association published the following blurb ahead of Perdue’s nomination:

[Sonny Perdue] supports factory farms, pesticides and genetically engineered crops. In 2009, he signed a bill into law that blocked local communities in Georgia from regulating factory farms to address animal cruelty, pollution or any other hazard. He took money from Monsanto and other pesticide companies for his gubernatorial campaigns. The Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a front group for the GMO industry, named Perdue their 2009 Governor of the Year.

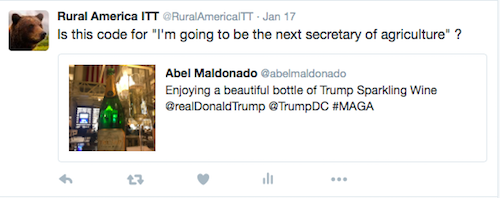

Hoping Trump might yield to pressure and diversify his largely white male cabinet at the last minute, many Democrats are no doubt disappointed. Abel Maldonado, the eldest son of Mexican-American farmworkers and former Lieutenant Governor of California was a leading contender for the spot as was Elsa Murano, former President of Texas A&M. Suggesting Trump’s final decision came down to the wire, yesterday evening Maldonado was tweeting pictures from Trump Tower. He commented on the hotel’s elegance while enjoying what (in the opinion of Rural America In These Times) could easily be misconstrued for a celebratory glass of champagne:

Following the announcement, both candidates expressed gratitude for their consideration and offered to support Perdue in any way they could. But Perdue has critics on the right as well. According to the neo-confederate Southern Party for Georgia website, Sonny Perdue is “bought and paid for” by the same special interests he once criticized while campaigning to get elected in the state. Reactions to Perdue’s nomination are still coming in from across the political spectrum and Rural America In These Times will be covering his transition closely in the coming weeks.

Why this pick was important

Rural voters ultimately made Trump’s path to 270 electoral votes possible and this particular cabinet selection was viewed by many as his first chance to deliver a perceived win for the economically struggling farming and mining communities that supported him. Perdue’s priorities and policies will determine if he meets rural expectations, but much more than agriculture falls under the USDA’s “umbrella” and the department’s policies affect every American.

President Lincoln established the Department of Agriculture in 1862. Pleased with its progress two-and-a-half years later, he called it “precisely the people’s Department.” Today the USDA, which consists of 29 different agencies and services that employ more than 100,000 people, is responsible for facilitating and implementing federal policy in a dizzying number of areas. In 2015, the Department’s annual operating budget was $139.7 billion.

Both the Forest Service (FS), which manages 193 million acres of public lands, national forests and grasslands (making it the largest natural resource research organization in the world) and Food and Nutrition Services (FNS), for example, fall under USDA supervision. In 2014, FNS oversaw the distribution of $74.1 billion in food assistance (SNAP) to 46.5 million low-income Americans.

Often criticized for using “tax payer money to pick winners and losers” in the commodity markets, USDA is perhaps best known for the perennial controversies surrounding the distribution of farm subsidies. But the agency also has offices in every state, conducts year-round agricultural research and performs nationwide food safety inspections. In addition to drumming up domestic and international marketing strategies, which include the formulation and implementation of national organic standards and production practices, USDA also has an agency aimed specifically at rural development (RD).

Under Secretary Vilsack, the RD office implemented numerous programs aimed at “revitalizing” rural economies. Indeed, for the last eight years, a steady stream of press releases announcing new affordable housing initiatives, high-speed internet infrastructure development projects, small business grants, nutrition programs to combat childhood obesity, support for utility cooperatives and renewable energy incentives for existing rural businesses (and more) could be found on the “newsroom” section of the Department’s website. Unfortunately, assessing the efficacy of these programs — determining whether or not they help the people who need it most — is nowhere near as easy. What is clear, however, is that recent federal efforts have failed to adequately ease the economic pain being felt in countless rural communities.

In a recent Grist article, “The Exit Interview: Ag Secretary Vilsack on Obama’s Food Legacy,” Nathanael Johnson dissects the popular criticism among food activists that the out-going administration essentially rolled over and let corporate agribusiness steer the ship. On whether such critiques of Vilsack’s performance were fair, Johnson writes, “Vilsack preferred to wield the carrot rather than the stick in trying to protect the environment. The USDA rolled out one voluntary rule after another, emphasizing cooperation and partnership rather than regulation and enforcement.” Voluntary or not, undoing any regulations that make farmers, ranchers, miners and energy workers jobs harder or less profitable has become a cornerstone of Trump’s pledge to rural America. The environmental implications of this promise are enormous.

Waiting until the last minute

Trump’s drawn out selection process caused plenty of frustration in the Ag world. As early as Dec. 14, Secretary Vilsack was expressing concern that Trump had not yet announced his cabinet pick. Prior to that, in November, the man assigned to assemble Trump’s agricultural team, a lobbyist for the agriculture industry named Michael Torrey, abruptly resigned when Trump banned lobbyists from being involved in his transition. (Before congratulating Trump for making good on campaign rhetoric, it’s worth considering the possibility that the army of well-connected millionaires now on his cabinet has rendered most lobbyists obsolete redundancies.)

As the weeks passed, numerous potential candidates made the trip to Trump Tower or Mar-a-lago to meet with Trump and/or vice-president-elect Mike Pence. Though a series of frontrunners emerged in the headlines, top-picks came and went as agricultural organizations began worrying further delay would compromise a “smooth transition.” All told, Trump may very well hold the record as the president-elect who waited the longest to announce his pick for agriculture secretary. The last five presidents, at least, announced their selections shortly after Election Day or sometime in December.

But the question of who should lead the Department of Agriculture — an academic, statesman or actual farmer — has been the subject of debate since the agency’s conception. In his essay, Lincoln’s Agricultural Legacy, Wayne D. Rasmussen writes that shortly after signing the bill that established the Department of Agriculture, Lincoln began receiving “much unsolicited advice, particularly in the columns of the farm press, on the appointment of the first Commissioner of Agriculture”:

Some urged the appointment of a distinguished scientist, others an outstanding “practical” man. A few periodical editors were certain that one of their number would be the best choice. However, Lincoln turned to Isaac Newton, a farmer who had served as chief of the agricultural section of the Patent Office since August 1861.

A similar debate has taken place in recent weeks and Trump has been the recipient of similarly unsolicited advice from a variety of newspapers and farm publications across the country. The majority were written by farmers in support of the idea that an actual farmer is best suited to run the Department of Agriculture.

The struggle continues

For sustainability advocates, this was never going to go well. Once Bernie Sanders left the race, this election cycle offered the food movement little in the way of a promising candidate. Hillary Clinton, who food activists nicknamed the “Bride of Frankenfood” for her financial ties to Monsanto and other agrichemical corporations, remained silent (or unconvincing) on too many of the issues this movement finds important.

In countries all over the world, resistance to corporation-controlled agriculture is spreading. As public awareness grows, the threats industrial methods and factory farms pose to soil, water, air, nutrition and climate are going to be increasingly difficult to ignore. Clashes between the powerful economic forces heavily invested in staying this current course, and the politicians with whom they are aligned, are inevitable. The fight for a less ecologically destructive approach to food isn’t going anywhere. You can’t put that toothpaste back in the tube.

Trump has repeatedly claimed that his administration will work on behalf of the American people, not corporations or special interests. Tomorrow we’ll all have a new president, and in rural America the world’s leading chemical, energy, biotech and food companies will be poised to further consolidate their wealth and power. Sonny Perdue is unlikely to stand in their way.

George Ervin “Sonny” Perdue III will be the nation’s 31st secretary of agriculture. (Photo: wepartypatriots.com)