“They Clearly Thought They’d Bought a Slam-Dunk Pipeline”—An Interview with Winona LaDuke

John Collins

Before Dakota Access LLC revealed that armed guards, pepper spray and German shepherds would be part of their public relations strategy on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota, the subsidiary of Energy Transfer Crude Oil Company, like many oil corporations, was already facing some uphill battles.

Two years ago, the fossil fuel industry’s most recent jamboree ended and oil hasn’t traded over $100 a barrel since. Natural gas production hit record highs in 2015, despite prices remaining low, and now the boom’s bust is serious. Smaller heavily-leveraged companies face bankruptcy while the bigger players scramble to reassure shareholders. Nobody seems sure when or if the good times are coming back. Meanwhile, the global market is oversupplied with oil (by as much as 10 percent according to one recent estimate). As a result, domestic prices currently hover in the low-to-mid $40-per barrel, recovering somewhat from a February low of around $27.

In recent years, as the quantity of oil and natural gas transported by rail surged, so did frieght costs. Pipeline capacity was deemed insufficient, prompting numerous new proposals. Though expensive to build and maintain, once they’re up and running, pipelines are the most cost effective form of oil and gas transport. Inevitably impacting the rural areas and farms they run through, some of these tubes get approved, others don’t. When packaged as safe, economically smart, job creating, energy-independence-facilitating projects, politicians tend to step out and embrace pipelines and the campaign contributions that swirl around them. This dance is best viewed as a romantic courtship — an economically beneficial mating ritual — not a series of sleazy random encounters.

To the 21st century casual observer, however, these arrangements appear counterintuitive. How many Americans, financially or otherwise, truly benefit from these projects? Why have we been hearing about the rise of sustainable, renewable energy for the last 40 years but not seeing much of it in our homes or on our roads? Shouldn’t we be trying to phase out our fossil fuel infrastructure, not expand it? Isn’t burning fossil fuels irreparably damaging our planet’s ecosystems?

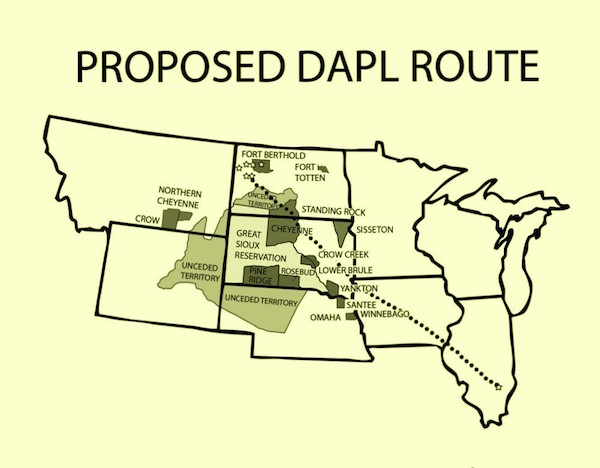

The Standing Rock Sioux, and their Native American allies, are not casual observers. The Dakota Access Pipeline — deemed too risky to put near the city of Bismarck’s water supply and subsequently rerouted downstream so that it could be burrowed under the Missouri River a half mile from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation’s boundary — will not continue on its current path. Native people won’t allow it.

(Image: Wilder Utopia)

This is unfortunate for Dakota Access LLC and its investors, who stand to lose millions of dollars, but it should not have come as a shock to executives. The regular occurrence of catastrophic environmental accidents, the knowledge that the extractive industry’s boom and bust employment cycles leave rural communities stranded in their wake, and a general understanding that corporate profits do not “trickle down” has, over time, galvanized a sizable opposition to new projects. Above all though, Native opposition to this pipeline is rooted in the empirical reality that clean water is essential to all life on Earth. Contaminated water kills.

There’s no denying that we remain utterly dependent on fossil fuels. On Wednesday, at an industry conference in Pittsburgh, Gary Heminger, the CEO of Marathon Petroleum Corp., now a minority stakeholder in the Dakota Access Pipeline, put it this way: “Despite the obvious truth that we make modern life possible, some activists try to portray fossil fuels — and the companies that produce, transport, and sell them — as villains.”

Heminger has a point. Oil companies, at the moment, do make “make modern life possible.” That does not mean that these corporations are working in humanity or the planet’s best interest.Unfortunately, this power is wholly contingent upon keeping an unsustainable paradigm economically viable regardless of better alternatives.

Winona LaDuke vs. Enbridge

Last week, as 336,000 gallons of gasoline were leaking from the Colonial Pipeline in Alabama, prompting officials to declare a state of emergency, I called Winona LaDuke, who was making her way from the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, where she lives, to the Sacred Stone Camp near Cannon Ball, N.D. where she has a tepee set up and keeps some horses. She’s been going back and forth from the site since April, most recently returning home to oversee the start of the wild rice harvest.

LaDuke, executive director of Honor the Earth, is no stranger to fighting pipelines. She has spent much of the last 4 years fighting Enbridge Inc., a massive energy delivery company based in Calgary, Canada, over their ill-fated Sandpiper pipeline — a fracked gas line out of North Dakota that was slated to run through her neck of the woods in Minnesota.

Depending on who you talk to, Enbridge is up there with Monsanto when it comes to corporate Darth Vaders. They’ve acquired a reputation for being ecologically reckless, eminent domain bullies. The former was reinforced when, in 2010, one of Enbridge’s underground diluted bitumen pipelines ruptured causing more than one million gallons of the dirtiest oil currently in production to spill into the Kalamazoo River not far from Marshall, Mich. Deemed the “The Dilbit Disaster,” the spill subsequently triggered the most expensive cleanup in U.S. history.

July 28, 2010 — A sign on a bridge above the Kalamazoo River warns people to avoid the water. According to forms filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, as of July 2016, Enbridge had paid nearly $1.2 billion to clean up the tar sands oil, not including more than $80 million in state and federal fines. (Photo: Bill Pugliano / Getty Images)

Enbridge crossed LaDuke when it decided that running their $900 million Sandpiper pipeline through Ojibwe wild rice lands was absolutely essential. The White Earth Nation disagreed. After a long battle, White Earth won — Enbridge pulled the plug on the project earlier this month. But now they’re back, this time as a minority stakeholders in the Dakota Access Pipeline; part of a joint venture with Marathon Petroleum Corp.

LaDuke explains that while they abandoned their plans for the Sandpiper line, Enbridge quickly jumped on the Dakota Access bandwagon, purchasing a 27.6 percent share for $1.5 billion. It’s a common practice among oil companies at the moment she says. “Bakken oil is down 85 percent in drilling right now, but all the oil is land-locked so they’ve been replumbing everything in North America — everybody’s trying to get a pipeline, any pipeline.”

Rural communities across the country are engaged in legal battles against energy corporations that few people will ever hear about. So what makes Standing Rock different? LaDuke says that this demonstration “didn’t just happen,” that to understand what led up to it requires a crash-course in “inter-generational structural racism, colonialism and oppression.”

Rural America: What’s going on in North Dakota?

Winona LaDuke: First, what I will tell you is nobody cares about North Dakota. People make fun of it. Everybody just tends to fly over and talk about how funny the movie “Fargo” is. Of course, in the meantime, no social movements have worked out there. The Sierra Club had one person and the ACLU had two — one for North and one for South Dakota. And the state became essentially the Mississippi of the North in regard to how it treated Indian people. [Check out Winona’s recent article What would Sitting Bull Do?.]

Then oil and gas companies moved in and succeeded with something called “regulatory capture” — that’s when you capture the regulatory process of a state so that it totally meets your needs. When this happens, states start doing weird stuff.

Weird stuff?

Weird stuff is when states do things like legalize low-level nuclear waste in municipal dumps. Who does that, right? Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials — TENORM — I testified at the hearings in North Dakota last year, but they approved it. They’re doing things like that. Right now the state of North Dakota is sacrificing the health of the people, certainly the Native people, and they’re also sacrificing the land.

Meanwhile the state has increasingly militarized — like, we’ve gone from Alpha, to Bravo and now we’re into Charlie in military terms. When we started there was $1.8 million of militarization going into North Dakota. Now there are drones. There are unmarked helicopters flying over, all kinds of surveillance and the road is blocked by the National Guard with a checkpoint. The other places we’ve seen this is in Ferguson and Baltimore (Ed. Note: This interview took place just prior to this week’s protests in Charlotte, N.C.) I was talking to a military officer the other day to get a sense of what rules of play they have. Do you have civil rights if the National Guard arrests you? But my question to the governor of North Dakota, Jack Dalrymple, who called the National Guard, is: How far are they going to go?

A state representative recently requested $6 million to increase this military presence. They’re obviously trying to provoke an incident so that they can deploy more force and demonize us. I have to ask again, “What’s it worth Governor? Are you really going to shove these people one more time?”

They’re up to like $7.8 million spent on militarization when they could instead be buying renewable energy for North Dakota. They’re calling this protection of energy security. It’s not. This is totally about greed. It’s totally about race. I did some math. What would these millions in military expenses buy the people? How many houses in Standing Rock or the town of Cannon Ball, with 200 houses, could get solar infrastructure?

Anyway, I suppose the governor thought that by blocking the road to the casino with his roadblock that he would put a squeeze on the casino, but you can’t get a room at the casino. It’s booked with journalists and people who weren’t prepared to camp. Business is booming in Standing Rock.

How is regulatory capture achieved? Lobbyists?

Lobbyists and money. The perfect example is Enbridge, my nemesis. They chose my territory. I didn’t choose them but they chose us. Enbridge creates something called North Dakota Pipeline Company and it incorporated the day before it received its status as a North Dakota public utility, which allowed it to use eminent domain. That’s what regulatory capture looks like— when a Delaware-based corporation is incorporated almost exactly the same time it received its status as a North Dakota public utility, giving it access to the power of eminent domain.

Winona LaDuke photographed while filming First Daughter and the Black Snake, an upcoming documentary about her work to stop Enbridge from building the Sandpiper Pipeline. (Photo: walkerart.org)

That case has been fought and last week Enbridge basically folded again and walked away. I’m talking about the case of James Botsford. Enbridge sued him for the right to throw pipe across his land. He basically told them, “You are going to have to take that from me, because I am not going to give it to you.” And so he fought them through the really seamy North Dakota regulatory process, in the court system. He was on appeal to the state Supreme Court and Enbridge just came in and said “We’re out — we’re paying your legal fees and we’re giving you back your easement.” They didn’t want a precedent set.

The point is, people have been fighting this for a long time.

So what kind of consultation was there with Standing Rock?

A letter. And that does not constitute consultation. We just went through this in the state of Minnesota. In our case, like Standing Rock, we have jurisdiction on our reservation and extra-territorial jurisdiction — the 1837 and 1855 treaties — and the federal government has a trust responsibility to protect that jurisdiction.

They talk about consultation, but in Canada that basically refers to a way to “get to yes” for an energy company. Consultation doesn’t mean that. One side has a right to say no. Just like a woman, you have a right to say no.

They truncated the process, that’s the other thing. The company divided it up so there were different segments of pipeline, so they didn’t do a complete impact statement on the whole line, which is what the tribe wants — a full environmental impact statement.

The state of North Dakota and the federal government say to the Standing Rock Tribe, “Well you guys didn’t really participate in our process.” Well, I myself have participated in Minnesota’s process. I went to like 30 hearings, and the system was totally skewed against us, but Minnesota is a state with at least the accouterments of sensible regulatory structure. The system in North Dakota is totally screwed.

There’s a lot riding, from what we understand, on the permits, which have not fully been issued and questions as to how they’re doing it etc.

In your view, what does North Dakota want?

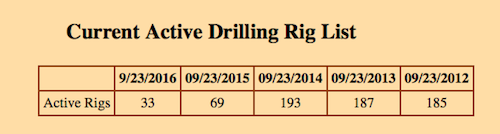

Oil and the money that comes with it. The North Dakota economy is crying right now because that boom is not booming. But look, I’m an economist and I could have told you this was going to happen. If you base your economy on the vagaries of a fossil market, your economy is going to be unstable. Wake up North Dakota, that’s a known fact. If ever there was a pipeline to nowhere, this is it. We’re talking about an 85 percent drop in drilling rates — there are more lawsuits about oil than there are active drilling rigs in the Bakken.

(Screen Shot: North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources)

How did support for this demonstration explode in the way that it did, attracting attention here and around the world?

It came down to the river and it came down to the permits. They’re barreling this pipeline towards Standing Rock from both the East and the West. And they’re barreling towards the Missouri.

When the company said they were getting to the river, they [the Natives] put a call out from the Sacred Stone Camp. People started coming. We have been out there, onsite, since April. I have a couple of staff that I basically loaned, but I don’t think I’ll be getting them back anytime soon. Since April it’s been growing. And then they started hitting more and more archeological sites and got this extra financial boost from Enbridge. So we followed the company out there. If it was too bad for our community, than it’s too bad for this community.

Tribal members and their supporters march in protest of the Dakota Access Pipeline. (Photo: Tomas Alejo / Desmogblog.com)

On September 9, the Obama administration (via the Departments of Justice and Interior and the U.S. Army called for a voluntary pause of all construction activity. How would you characterize this federal reaction?

The federal reaction, from my perspective, is that they’re trying to keep things from blowing up. They know that this is a problem. Native people are not likely to back down. Everybody in the country watching this. Churches and cities like St. Paul and Seattle and labor unions are coming out and saying you can’t do this to Standing Rock, you can’t just run over these people with dogs again. It’s not going to work. The world is watching this.

The current oil supply glut is global. How does this affect things?

That’s right. The Saudis will likely keep dumping because that’s their economy and they’ve got plenty of it. In North Dakota, it has to be about $60 a barrel to get this stuff out of the tar sands — it’s expensive oil. And rigs are literally being abandoned. So there’s a slump and North Dakota is trying to figure out what it’s doing.

The last couple of years driving out to New Town, N.D., as a single woman at night you’d be terrified because of all the rigs and lights and you figure there’s meth heads or who-knows-what out there. This year, there’s nobody on the road.

North Dakota politicians, like so many politicians unfortunately, lack vision. What they want is someone to offer them a daytime TV show that they can get commercials in, and that’s the extent of their political vision. But that’s not what we need.

What do we need?

We need infrastructure for people. In northern Minnesota, we have 300 something miles of pipe just sitting there, from the Sandpiper pipeline, that they’ve now announced they aren’t going to use. And I’m like, send it to Flint, turn it into wind turbines — do something with it. We have a D in infrastructure in this country. Bridges crumble, gas mains explode, city blocks blow up — we need infrastructure, but this is not infrastructure that will help us. This is infrastructure for oil companies. It’s going to hurt us.

They don’t want to fix old pipes. They want to throw in new pipe. It’s like — clean up your old mess before you make a new one. No wait, you don’t get to make a new mess. That’s my position. I’m a prudent woman. I can’t imagine spending millions and millions of dollars and wasting it.

What’s the camp been like recently?

There have been a couple thousand people out there. One of my friends just returned and said it’s muddy because it rained really hard, but I have 4-wheel drive and some horses. Soon it’s going to get cold and people are going to need yurts and trapper tents to stay in, but there are going to be people that are going to stay for a long time. We can out wait these guys — we can out wait an oil company getting pressure from shareholders.

Do you think they know that?

In my experience, Enbridge is clueless — clueless as to what they were coming up against. These oil companies are a lot like Custer, no idea what they’re walking into. Enbridge came down here with this plan to put in a pipeline, they thought that they missed the reservation because they’re bad at math and geography. They thought they could get by without telling us where the route is and making it classified so we couldn’t comment on it — you know, stupid shit like that. They pull all this repressive stuff and then the tribes get mad. But the tribes aren’t budging. No tribe wants more oil up here.

So they hire these guys — we call them the Indian whisperers — they’re the “tribal relations specialists.” It’s a total failure! We’ve burned through two Indian whisperers and now I’ve got an Indian listener, that’s what I call her. I visit with her and ask, “How’s it going?”

They clearly thought they’d bought a slam-dunk pipeline. I’m like, well that is not a very intelligent corporate decision.

How often do you visit with the Indian listener?

Once every couple of months. I ask them questions.

What’s that like?

Our dates are like this: I say, “So I would like a copy of the structural anomaly report for line 3, can you get that for me?” They don’t really produce much for various reasons so then I say things like, “Hey, how come you guys just invested in off-shore wind off of the British Isles but won’t invest in wind energy here?”

No response.

Speaking of renewable energy alternatives, how realistic are they right now? Because plenty of people are saying that we need this oil and the infrastructure to transport it.

Oh my God, that is so sad. Didn’t you go to any of my lectures? Not one lecture or what?

I’m not saying “me,” I’m saying that this is a narrative we hear a lot — that all these activists better stop driving cars and live without their lights on.

Okay, lecture number one: 57 percent of energy is wasted between point of origin and point of consumption in the United States. We have archaic, inefficient systems — archaic systems of extreme extraction and this is what you get. So to the people saying you’re not going to meet present demand with renewable energy, the correct response is: “Why would you want to?” Why would you want to meet 57 percent inefficiency? It might even be higher than that now, but all these things that we talk about are in the context of a very inefficient system. That’s the first thing.

The second thing is the combustion engine itself. I’m really into this woman named Mara Prentiss, she’s a physics professor at Harvard (yes, I read my Harvard Magazine) and she says we’re going to have a new energy transition, but that we’re going to have it because physically it’s required. If you read her essay, you find out that the combustion engine is 16 percent efficient. You’ve got a drive train and all these pieces in it. But do you know efficient an electric car engine is? Over 60 percent efficient…

Are you saying that cleaner energies are being supressed because oil is profitable?

Well yeah. Didn’t you ever see Who Killed the Electric Car? C’mon — I’m just giving you shit, but what you said is absolutely true. In the meantime, we are trying to relocalize. I’m working to develop a regional/tribal food economy and energy plan where I live because there’s no point in waiting. We could be waiting for thousands of years.

With solar, it seems possible that someday everybody could essentially be their own utility, generating most of you use where you use it?

That’s what has to happen, and we need to push it sooner rather than later. From my perspective, Standing Rock is like this opportunity for the future. That pipeline is not going to help these people.

There’s this woman named Debbie Dogskin who died a few years back when the price of propane jumped — she died on Standing Rock, right next to the Bakken oil fields, she froze to death because she couldn’t pay her heating bill. So I ask myself, how would this pipeline help Debbie Dogskin? Who does this help, you know? It only helps the oil companies. So the answers are super easy for me — it’s a justice issue.

Standing Rock has a D minus in infrastructure and what those people need is a way to heat their houses. So you do passive solar thermal, or solar thermal, that’s what you do. And they need to come up with some other cool stuff, maybe some wind, I don’t know, but there are a lot of options.

Standing Rock needs a plan. I would call it the Sitting Bull Plan for Standing Rock. In fact, I met with the tribal chairman a couple of times and was just on a conference call with him and he’s interested in it. At the end of this, not only does Standing Rock not want a pipeline, they want something that makes sense for their community. The village of Cannon Ball could be a place where things make sense. To me that’s worth everything.

How do you see this resolving itself?

I think what’s going to happen in the end is that we are going to keep fighting this company. They are not going to get that line in. They might have to go north of Bismarck, they can start over there but I don’t know if they’ll even be able to do that because there are not a lot of pipelines going in right now. I think in the end the Standing Rock tribe is going to get a big solar project and maybe some wind and hopefully some justice.

We’re going to win. But I don’t know how it’s going to go getting there, because the governor obviously has no regard for civil or human rights or constitutional rights. The governor might be trying to extract a little blood out of us. I would say that that would be his M.O.

But I pray everyday and we’re working on our end. I’d like to see the river recognized — its right to exist — because right now they’re compromising our health. People need to pay attention to this because it’s part of a national problem. We need to ask ourselves, as a country, where we’re going. Do we want to compromise everything for an addiction to oil?

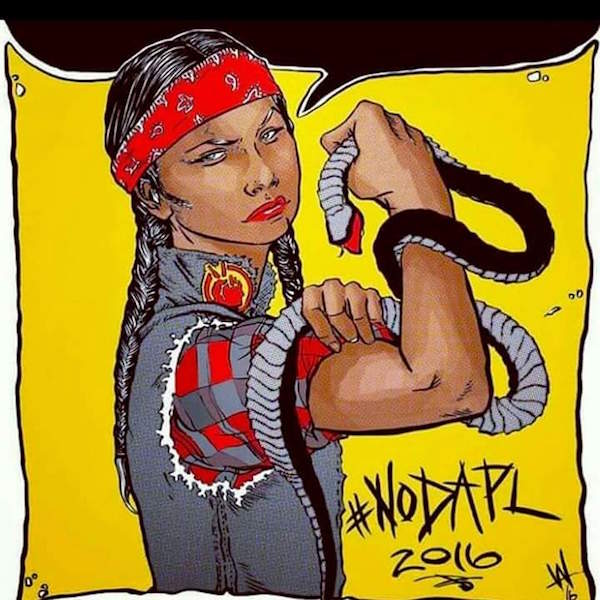

#NoDAPL protest poster. According to Camp of the Sacred Stones, old Lakota prophecy speaks of a black snake (zuzeca sape) crossing the land, bringing with it destruction and devastation. (Image: Weshoyot Alvitre / Twitter)

*Interview was edited for length and clarity.