In May 2010, as British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig was still in the process of uncontrollably gushing 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, the Washington Post featured an interview with the former CEO of Shell, John Hofmeister, about a new book he’d written called Why We Hate the Oil Companies.

“The short answer,” Hofmeister said, “is because the government has taught us to. Government’s failure over many decades to make the difficult decisions and choices with respect to our energy future means they look for a scapegoat when things go wrong. The primary scapegoats they choose are the oil companies, whether about prices, environmental issues or supply issues; it’s always the oil companies’ fault.”

This week, a debate has emerged about whether or not it makes sense to link the recent Canadian wildfire to anthropogenic climate change and, by extension, the fossil fuel industry. Climate activists are accusing the mainstream media of failing to publicize the connection, victims of the fire have called those who did insensitive, while others, who agree the planet is heating up, caution against hinging the cause of the flames too definitively on warming trends.

Fort McMurray

The wildfire burning in northeastern Alberta, now moving toward Saskatchewan, prompted the evacuation of nearly 100,000 people in and around Fort McMurray — an energy boomtown located 270 miles north of Edmonton in the Athabasca oil sands, the largest known reservoir of bitumen (heavy crude) in the world.

It was the largest wildfire evacuation in Canada’s history, a massive escape involving convoys of cars and trucks heading south on Highway 63. Residents trapped in the city were airlifted to safety. Though the loss of human life was prevented, much of the infrastructure of the urban service area (a Canadian term denoting a community with a population of 10,000 or more) has been compromised and 10 percent destroyed. Twenty-four hundred homes — and everything families kept inside them — were lost to the flames. Insurance costs are already projected in the billions, making the fire the most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history.

An aerial view of the Athabasca oil sands. (Photo: Wikimedia commons)

The boreal forest

The boreal forest, also known as taiga, that surrounds Fort McMurray is part of the Earth’s largest terrestrial biome — a swath of similar flora and climate stretching throughout the high northern latitudes. On a map, the boreal zone rests just above our temperate forests to the south and right below the northern tundra’s permafrost. In North America, it covers nearly all of inland Alaska and Canada but dips into northern Minnesota and Wisconsin (where we call it the Northwoods) before winding east through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula on its way to Maine. The boreal forest continues like a halo on top of the northern hemisphere, crossing through much of Russia, Scandinavia, parts of Iceland, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and northernmost Japan. The largest portions undisturbed by humans are found in Canada and Russia. According to The Nature Conservancy, “the boreal forest accounts for one quarter of the intact, original forests remaining on Earth.”

(Image: borealforestinamerica.blogspot.com)

Though its biodiversity varies by region, the boreal forest consists largely of densely spaced coniferous trees such as black and white spruce, tamaracks, firs and jack pines. Deciduous trees like birch, alder and poplar can thrive in the forest’s slightly-less cold areas. In the Northwoods, the conifers are mixed with oak, maple and elm. Far to the north, the trees give way to lichen-floored forests that grow more open and sparse as temperatures drop.

White and black spruce in the forest along Kontrashibuna Lake in southwestern Alaska. (Photo: nps.gov)

A fire-dependent ecosystem

The boreal forest and the ecosystems within it are fire-dependent—not only do they require periodic burning for regeneration, but they exist in their current state as a result of previous fires dating back to the end of the last Ice Age. The jack pine, usually the first to start growing after a burn, has evolved to rely on fire to spread its seeds — producing “seratonous” or resin-filled cones that remain dormant until fire melts the resin, exposing the seeds inside. Spruce trees usually follow, kicking off a 140 to 200 year cycle of growth before mature trees begin dying off and decomposing.

All forests simultaneously release and store carbon as old growth decays and new growth develops. Like other forests, the boreal is a vital part of the planet’s “carbon cycle” — the never-ending transfer of carbon from land and water through the atmosphere and living organisms — on which all life depends.

Over time, a tremendous quantity of carbon (208 billion tons in Canada alone) has been captured and stored in the boreal forest’s floor. According to Forest Fires in the Boreal Zone: Climate Change and Carbon Implications, a 2004 report issued by the University of Freiburg, although ecosystems found in the boreal forest zone cover less than 17 percent of the earth’s land surface, they contain “in excess of 30 percent of global terrestrial carbon.” Of course, as a wildfire burns, that stored carbon is released.

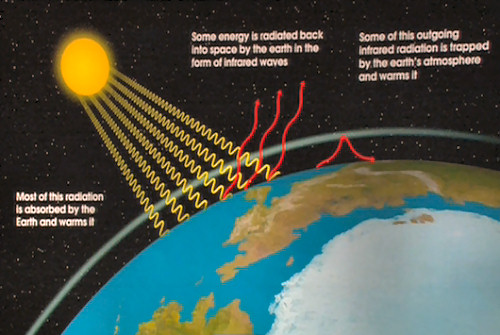

Greenhouse gasses, including carbon dioxide, affect the planet’s temperature by trapping infrared radiation (from the sun) inside the atmosphere and sending some of it back to the surface, causing warming. The right balance causes the temperatures we’ve come to expect but too much, as we’re told again and again, is a recipe for natural disaster.

A warmer winter and nonexistent snowpack due to particularly dry conditions in northeastern Alberta significantly raised the likelihood of fire. Unfortunately, the same can be said for other parts of the continent as our planet appears to be cranking out freakish weather-related patterns with increasing regularity. Arguing over whether these perceived abnormalities are exacerbated by anthropogenic carbon emissions, or part of an industry-crippling wealth-redistribution scheme perpetrated by eco-pinko-commie-socialists remains a popular pastime.

Basic diagram depicting the Greenhouse Effect. (Image: chriscolose.wordpress.com)

The controversy

Understandably, the last thing the victims of the Fort McMurray fire wanted to hear as they arrived at their temporary lodgings in Edmonton (many unsure if their homes had been destroyed or not) were climate activist critiques of the fossil fuel industry’s role in global warming and the disaster.

The same would be true in any community, but the region is sitting on top of the world’s third-largest oil reserves and the city and economy of Fort McMurray was founded (and sustained) with revenue from the Athabasca oil sands. There, as in parts of the United States, the extractive industry has (directly or indirectly) provided employment and a decent quality of life for thousands of people and resources for other communities to consume. Of course, many companies have also left behind economically devastated ghost towns, contaminated waterways and, in numerous cases, irreversible ecological harm. When news of the fire broke, some were quick to imply climate change was the primary culprit, spawning zealous comments from others who claimed the fire was some kind of divine retribution for the industry’s environmental destruction.

In response, many Canadians expressed sadness and outrage at the insensitivity of those in the media who immediately twisted the tragedy into politics. Blair King, a chemist in British Columbia, called out certain climate activists, of whom he is a long-time critic, for trying “to use this natural disaster to score points.”

His criticism was subsequently cited in a Slate piece by Eric Holthaus who denied that his motive for writing a previous article—Wildfire Rips Through Canadian City Causing 80,000 to Flee. This is Climate Change—was ill-conceived. He writes:

“I want to be clear: Talking about climate change during an ongoing disaster like Fort McMurray is absolutely necessary. There is a sensitive way to do it, one that acknowledges what the victims are going through and does not blame them for these difficulties. But adding scientific context helps inform our response and helps us figure out how something so horrific could have happened. We’ve reached an era where all weather events bear at least a slight human fingerprint, which, as Elizabeth Kolbert points out in the New Yorker, means “we’ve all contributed to the latest inferno.” That’s a scientific fact. We need to talk about what we want to do with that information. Since climate change is such a pressing global problem, there’s no better time to have that conversation than now — when we can see what exactly inaction might continue to cause.”

Meanwhile, newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, was simultaneously praised and reprimanded for his tempered response. Asked whether climate change was a factor in the fire, he replied, “Pointing at any one incident and saying well, this is because of that, is neither helpful nor particularly accurate.”

Because climate scientists have been predicting the increased likelihood of wildfires as a result of climate change for years, when an oil town in the middle of a pristine forest went up in flames, people were bound to make the connection. There’s nothing wrong with acknowledging what we know (and don’t know) about the science of climate and wildfires, even in the middle of a conflagration. Doing so in a way that disrespects people, whether they’re dealing with a life-changing crisis or not, is counterproductive but easy to do on the internet. Ultimately, Trudeau was right that none of it was particularly helpful.

What would be helpful here in the United States, perhaps, would be for people and their elected officials to honestly acknowledge that any transition to cleaner, renewable energy must inevitably confront the economic realities of an internationally entrenched, petroleum-based power structure that’s been intricately tying itself to the political decision-making process since the discovery of oil in Oil Creek, Pa., in 1859. In other words, accepting that radically changing how we keep the lights on or drive down the street will eventually require the uncomfortable severing of long-standing corporate/government arrangements. As it stands, it doesn’t look like we’ll be “going green” until “Big Oil” discovers a way to make it comparably profitable and gives Uncle Sam the okay to proceed, but maybe it doesn’t have to be that way.

One would think that now — at a time when many scientists are warning us about the risks of fossil fuels, oil prices are low and millions of people desperately need new skills and living-wage jobs — would be a good time to pursue wide-scale alternatives in earnest. Some progress is being made, but federally subsidized, large-scale solar power projects, for example, have a troubling habit of going belly-up, while the installation of solar panels on houses in states like Florida is being actively opposed by Koch-funded organizations.

In the meantime, some economists have warned that the fire will have negative repercussions throughout Canada’s economy in the second quarter of 2016. As much as 25 percent of Canadian oil production was halted due to the blaze and all commerce in the Fort McMurray municipality remains shut down.

The oil industry, and communities that depend on it, have already been reeling. The price of oil started plummeting at the end of 2015 on signs of a global supply glut and prices have yet to recover anywhere near their previous highs. Financial markets, desperately looking for any signs of cuts in international oil production, briefly rallied on news that the Fort McMurray fire had halted operations. As of yesterday, May 10, oil traded up 2.8 percent as “Canada, Nigeria outages counter stockpile concern” and the Dow Jones Industrial Average had its best day since March.

The Alberta wildfire, nicknamed ‘”the Beast” by firefighters, seen from space on May 4, 2016. (Photo: Canadian Press)