Scalawags, Rednecks, Mudsills and Swamp People: 400 Years on America’s Fringe

John Collins

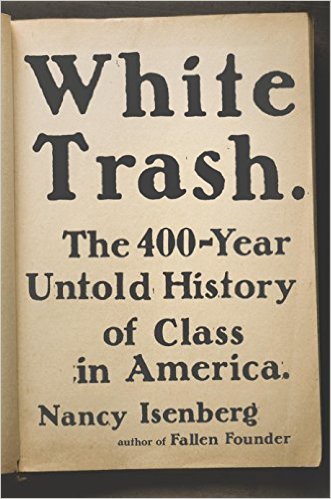

History favors uplifting interpretations of our origin story — tales of amiable Pilgrims, free markets, bootstraps and an escape from tyranny, mercifully packaged for a general audience — but Nancy Isenberg did not get the memo. In White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, Isenberg does to white American history what Christopher Nolan did to Adam West’s Batman.

Out in time for summer, White Trash will ruin your day at the beach.

Before rednecks, trailer trash and swamp people, there were squatters, crackers, clay-eaters and white niggers. Before that, there were the lubbers, bogtrotters, scalawags and offscourings — Britain’s “waste people” sent by London’s elite to set up shop in the colonies. All terribly regrettable in hindsight, but, in addition to slavery and the slaughter of this continent’s indigenous people, our equality-themed “land of opportunity” also required (and still does) a persistent class of poverty stricken white people. Over the centuries, these born-to-lose, alcohol craving, sexually promiscuous degenerates have proven useful.

In the beginning, for example, they could be rounded up and dispatched like expendable drones to recently acquired hostile territories. Many died, starving and toothless, but they were replaceable. Eventually, as Isenberg tells us, enough fertile young women and booze were sent across the Atlantic (in exchange for tobacco) to assure their sustainable (albeit miserable) reproduction. Much later, during the Civil War, their children’s children would provide cannon fodder for the South’s planter elite. By this time, an indigent class, believed to be beyond all hope of social reform, had been widely accepted as an unfortunate but inevitable societal fringe — a “permanent breed.” Generations of white people have been born into poverty ever since — “curious” social fixtures who periodically collide with the national mainstream, often for our entertainment, before dissolving (again) into the background.

Today, in towns we’ve never heard of, in rural counties from coast to coast, a variation of the cycle continues.

The instruments of other men

If the reader can manage to extract him or herself from the (well-researched) centuries of human suffering Isenberg lays bare, White Trash can be fun to be read. The “intractable poor” have been driving the powers-that-be bananas for hundreds of years. Their wretched idleness has threatened civilized commerce since Jamestown! At first their tendency to fornicate irresponsibly, like “wild animals” was good for business. But these “waste people” were increasingly seen as a risk to the larger, more promising gene pool. Fearing a day when their numbers might become unmanageable — their habits and hygiene contagious — the progeny of this “lesser stock” were the source of great anxiety to some of our nation’s most renowned leaders, intellectuals and visionaries.

From the first imported 17th century vagabonds to Duck Dynasty’s recent success on television, White Trash tracks changes in the national perception (and function) of the ever-present poorest of the poor. The author quickly makes clear, “When it came to common impressions of the despised lower class, the New World was not new at all.” The Jamestown hierarchy, for example, “borrowed directly from the Roman model of slavery” — a system in which “abandoned children and debtors” were fair game for forced labor. The Puritans also believed inequality and submission of the lower classes was “a natural condition of human kind.”

Citing numerous court cases brought forth by masters charging their servants and slaves with everything from “disobedience…idleness, theft, rudeness, rebellion, pride and a proclivity for running away,” Isenberg dispels the myth that these arrangements were accepted as “natural” by the exploited.

In 1696, after enough troubling infractions, one prominent minister published A Good Master Well Served—a manual intended to remind servants and slaves what they were: “Animate, Separate, Active Instruments of other men.” He suggested that their tongues, hands and feet “move accordingly.” In other words, the new world was still a place in which a person could be born free but, through a lack of status, become otherwise. Throughout the book, Isenberg identifies an often disturbing preoccupation with human breeding among the ruling elite — first as a means of generating the numbers needed to colonize the land, but increasingly as something that could be manipulated to better ensure new American offspring of quality (class).

Cringeworthy comparisons of fertile women to livestock abound.

As the colonies grew, so did awareness of class and racial tensions. The commercial sale of enslaved people allowed a few wealthy families to thoroughly monopolize colonial farmland. By 1700, in Virginia, there was no available land left for indentured servants. The lowest of freemen could either become tenant farmers or move “off the grid” into the surrounding wilderness. A similar dynamic was taking place elsewhere. Working land that wasn’t theirs — filthy and often physically deformed by grim living conditions — those on the outskirts became known as squatters. In 1737, the Governor of North Carolina described this sort as “the meanest, most rustic and squalid part of the species.”

Suffice it to say, they proliferated.

Idleness and poverty

Though the epithets change, for centuries this perceived subset of the white population — those deemed in some way physically or mentally inferior to the rest and therefore destined for poverty — has been defined by and vilified for its “idleness.” From the perspective of the ruling class, idleness exists as the worst of character flaws — a moral failing that needs to be squashed or otherwise conquered in the name of productivity. Not only did the colonies import those fitting the description, they continued to embrace the idea that these people were born bad and hopeless. It almost starts to make sense that the default reaction (of mainstream hubs) to urban homelessness, has been to relocate the unsightly manifestations of their poverty — the tents, the shacks, the camps.

In other words: if you can’t change them, keep them moving.

When Benjamin Franklin published Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind in 1751, he was well aware that the Pennsylvania backwoods were filled with some unsavory types. But he popularized a notion that issues of class would eventually be settled by westward expansion. After making a thin but interesting case that Franklin personally harbored “deep contempt” for the poor, Isenberg writes that he hoped the “forces of nature would carry the day, that the demands of survival would weed out the slothful, and that the better breeders would supplant the waste people.” (Interestingly, Franklin’s theories on human social behavior were often based on his extensive study of pigeons and ants.)

Similarly optimistic notions and a faith in natural market forces’ abilities to eliminate poverty were championed by Common Sense author Thomas Paine though Isenberg notes, “that vast numbers of convict laborers, servants, apprentices, working poor, and families living in miserable cabins are all absent from his prose.”

What would become of them?

Thomas Jefferson, according to Isenberg, viewed human behavior as “conditional, plastic, adaptable” and believed freedom alone would foster generations who eschewed “idleness” in favor of an agrarian love of land and country. Though a powerful force against the aristocracy of the day, Isenberg writes that when it came to the post-independence population, Jefferson “was not above social engineering.” Perhaps foreshadowing the Darwinian and eugenics movements that would gain chilling popularity shortly after the Civil War (fascinatingly covered in White Trash), Jefferson wrote the following in his Notes on the State of Virginia: “The circumstances of superior beauty is thought worthy of attention in the propagation of our horses, dogs, and other animals…why not in that of man?”

John Adams, meanwhile, viewed the “passion for distinction” as the great driver of men, saying, “There must be one, indeed, who is the last and lowest of the species.” In other words, as Isenberg puts it, Adams believed that Americans not only needed to work hard, “they needed someone to look down on.” This perspective, perhaps the most accurate of all, reveals the unspoken obvious:

There cannot be a middle or upper class without a lower.

There just can’t. Yet, somehow, we seem to have spent the last four centuries going to cruel and absurd lengths to avoid making direct eye contact with reality.

Racial differences have offered convenient grounds on which to compartmentalize people, but they clearly don’t always do the trick. Invariably, class picks up the slack in the act. Isenberg puts it this way: “Moved by the need for control, for an unchallenged top tier, the power elite in American history has thrived by placating the vulnerable and creating for them a false sense of identification — denying real class differences whenever possible.” She calls this deception “dangerous” partly because “the relative few who escape poverty are held up as models, as though everybody at the bottom has the same chance of succeeding through cleverness and hard work, through scrimping and saving.” Of course, the 21st century poor (a club with booming membership) know differently.

Throughout the book, Isenberg explores numerous examples of how white trash stereotypes have been reinforced in entertainment and leveraged for political gain. Isenberg draws compelling parallels between the rise of Andrew Jackson — his unrefined common man appeal — to the candidacy, style and tactics of Donald Trump. In a chapter called Cult of the Country Boy, she unpacks, among other pop-culture phenomena, the implications of Elvis buying poor folks Cadillacs.

Contrary to the free market narrative, Isenberg states clearly: “Without a visible hand, markets did not at any time, and do not now, magically pave the way for the most talented to be rewarded; the well connected were and are preferentially treated.” (Interestingly, following a relevant critique of Deliverance, Isenberg notes that Billy Redden — the 15 year-old boy who plays dueling banjo with Ronny Cox at the start of the film before all hell breaks loose — still lives in Georgia, is in his fifties and has trouble getting enough hours at Wal-Mart to make ends meet.)

No matter what we tell ourselves

White Trash provides an honest (and therefore important) look at four centuries of misrepresentation and exploitation — complete with the conventional wisdom, pseudo-science and armchair anthropology that sustains it. As she strings together the story of our nation’s inherited obsession with class, Isenberg asks the question: “How does a culture that prizes equality of opportunity explain, or indeed accommodate, its persistently marginalized people?”

The answer: massive quantities of denial.

If there’s any hope of maintaining the illusion that we’ve been living in a truly equality-driven democracy, then a dogged refusal to acknowledge the hypocrisies in our official history is essential. While maintaining that ours is a union rooted in equality, we’ve gone tremendously out of our way to cultivate a permanent kind of separateness. That seperateness, White Trash argues, is an illusion. As Isenberg writes, “Those who fail to rise in America are a crucial part of who we are as a civilization… They are renamed often, but they do not disappear. Our very identity as a nation, no matter what we tell ourselves, is intimately tied up with the dispossessed.”

(Image: amazon.com)