PHOTO-ESSAY: Caravan of the Mutilated

Having lost limbs on the dangerous trip across Mexico, 13 Hondurans sought an audience with President Obama—but are instead facing deportation.

Joseph Sorrentino

Thirteen Honduran men who travelled across Mexico as part of La Caravana de los Mutilados (the caravan of the mutilated), entered the United States at the Eagle Pass Port of Entry on March 19. They were immediately detained by Border Patrol agents and taken to the South Texas Detention Facility in Pearsall, Texas, where they’ve been held since.

The men belong to the Associación de Migrantes Retornados con Discapacidad (AMIREDIS), an organization for migrants who lost limbs riding the cargo trains collectively known as La Bestia through Mexico. Their goal was to reach the United States and to speak with President Obama. “We want to see Obama so he can know the nightmare that immigrants face,” says José Luís Hernandez Cruz, the organization’s president. “Ask him to help generate jobs in Honduras so we can stop migrating.” As unlikely as that meeting seemed at the beginning of their trip, it appears to be even less possible now. Two of the men agreed to deportation, and pressure is on to deport the rest. The White House declined to comment for this story.

About 400,000 Central American migrants enter Mexico each year, many of them riding La Bestia as they make their way to the United States. Most are fleeing from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, countries that are among the poorest and most violent in the world. Migrants report that gang violence is rampant in larger cities in their country, violence usually perpetrated by the Maras, the most vicious gang in the Americas. Among other things, they charge businesses a cuota (fee) for doing business and force young men to join their gang. A refusal to do either will result in that person — and often family members — being killed.

The journey through Mexico on La Bestia is dangerous, as the men in the caravan learned too well. Migrants may be killed or seriously injured when climbing the train; they may fall off while asleep; they’re robbed by gangs and kidnapped by drug cartels; women are raped. No one knows how many are killed or injured each year. Despite the horrors of the trip, they ride the train because, as one advocate says, “It’s the most economic way for them to travel.”

Cruz first tried to get to the United States in 2004 but was caught in Mexico and deported. Undeterred, he tried again the following year. “For Central Americans, the U.S. is like the promised land,” he says. On that second trip, he passed out on top of the train and when it shook, he fell off, losing his right arm, right leg and part of his left hand. “Thanks to God, I fell close to a city and was found,” he says, adding. “That ended all my dreams.”

Adán Escobar Ceballos, another member of AMIREDIS, said about 25 people in the group meet regularly in El Progreso, Honduras. They give one another support and stage events to bring attention to their situation and to expose the dangers of traveling on La Bestia. This year, 17 men decided to form a caravan and head to the United States, leaving Honduras on February 26. They arrived in Mexico City in early March and staged a small protest in the zocalo, the city’s main square. There, they held up signs describing their plight and talked with people about their journey to the United States. At the time, it was uncertain what would happen if they made it to the U.S. border, but 13 of the men decided to press on.

Nine of the men are being represented by attorneys from the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES) and are seeking refugee status, claiming they don’t believe the Honduran can protect them should they be returned to that county. RAICES is concerned about the conditions under which the men are being held. “They are not being provided with prosthetic socks or bandages,” says RAICES’s executive director, Jonathan Ryan, who is serving as their attorney. “They have no cleaning solutions to clean their prostheses, they’re not provided with wheelchairs … and they have all lost weight.” According to Ryan, the group’s president, Cruz, was put in isolation upon arrival, supposedly because he needs special medical treatment, although Ryan says the facility would not specify what that treatment was.

“He’s not been able to make phone calls, and he’s not had contact with the other men,” Ryan says. At one point, Cruz told Ryan, he was being transported to a meeting and was shackled. Because of his missing limbs, it was difficult to shackle him, so, Cruz says, they put his one arm into a belt. “It’s degrading, inhumane and dangerous,” says Ryan. “What if he fell?”

Cruz says he went on a five-day hunger strike to protest his isolation. Others in the caravan are now considering a hunger strike. All of the men are suffering. One of them has developed a fungal infection, and others are afraid of the same thing happening to them. Without wheelchairs, they are at greater risk when showering. Ryan has requested that the men be granted parole because the facility is unable to provide proper medical care for them. The request was filed on March 30, and the men are still waiting a decision.

MEXICO CITY—The men’s prostheses stand in front of their donations box in the Zócalo, Mexico City’s main square.

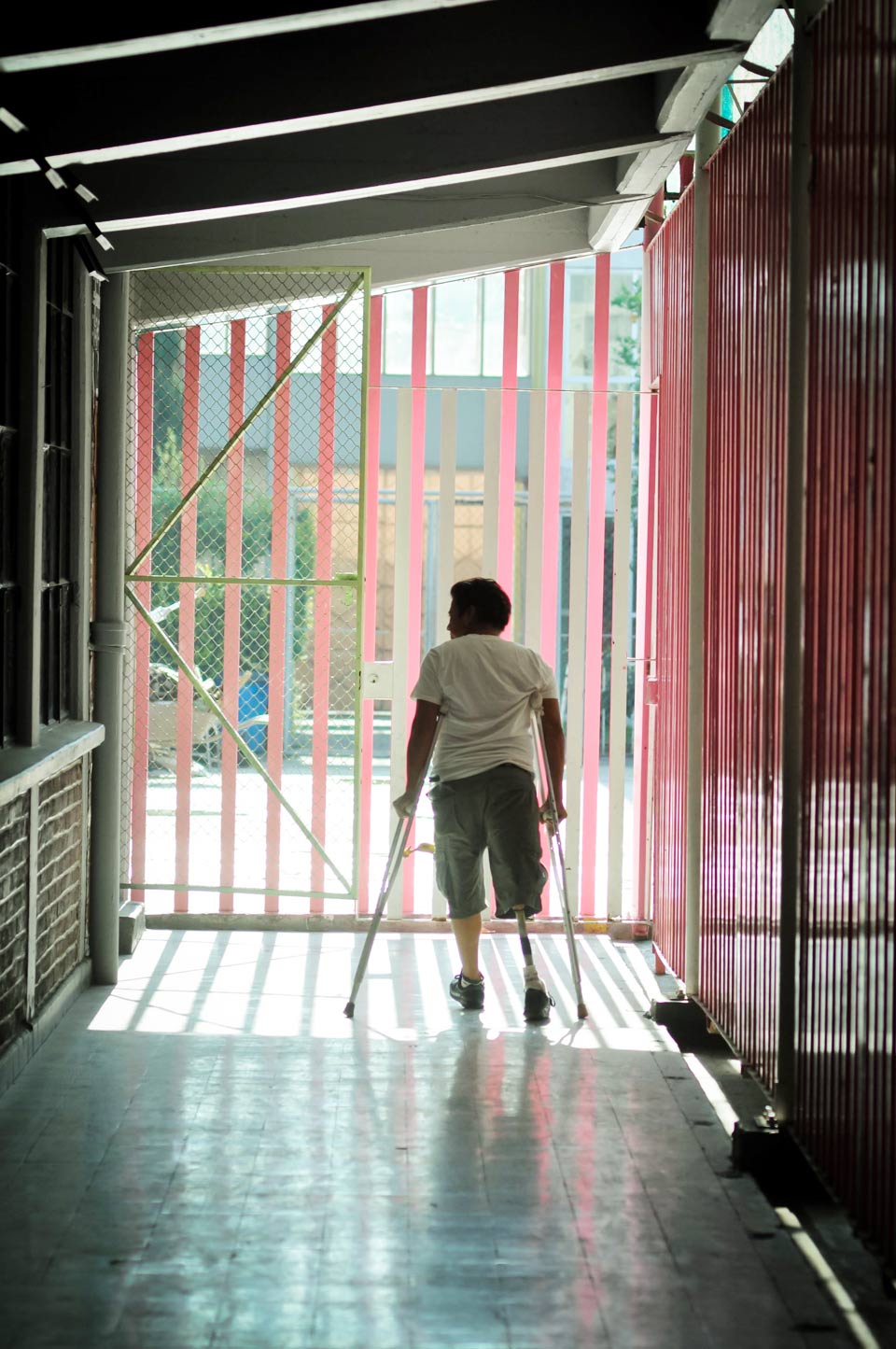

The group struggles to navigate the stairs leading down to the Metro.

José Alfredo Orea Santo’s injury prevents him from harvesting bananas, so he now earns a little money making piñatas.

Adán Escobar Ceballos was deported after living in the U.S. for nine years, then injured when he tried to return in 2004 in order to reunite with his 18-year-old son.

Luis Alonso Colimbre, who lost his right leg to La Bestia, walks down a hallway at a shelter for migrants in Mexico City.

At the protest in the Zócalo, a sign reads, ‘We do not want more migrants disappeared, kidnapped and mutilated’.

Wilfredo Filio Garri, who can no longer drive a taxi, begs for money on the street.

Photos by Joseph Sorrentino. All rights reserved.