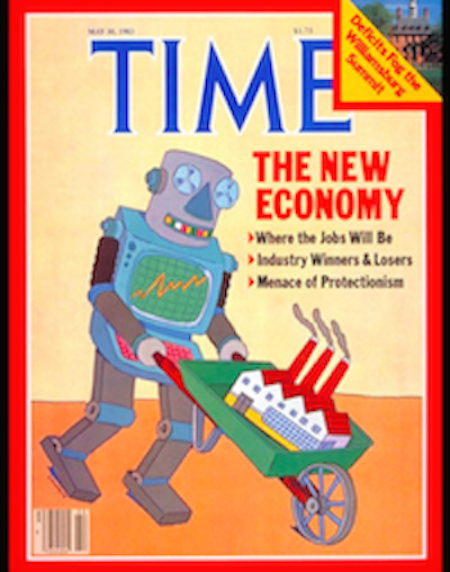

In May 1983, the cover of Time Magazine featured an image of a klutzy looking robot. It had a primitive computer for a body, analog tape reels for eyes and was pushing a wheelbarrow with a factory in it. The chimneys on the factory, resting tilted in the wheelbarrow, were still smoking as the robot trucked it off. The headline read: “The New Economy” and further enticed readers, in smaller print, with “Where the jobs will be” and “Industry winners and losers.”

As a buzz phrase, “the new economy” got legs during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s. It acknowledged the country’s shift away from manufacturing towards technology-driven jobs. Today, however, chatter on the subject is more often than not predicated on the notion that our systems themselves are failing, en masse — not just the majority of Americans who are living stagnant paycheck to stagnant paycheck, but failing a planet that’s starting to look like it spent the last 250 years smoking too many cigarettes.

Granted, for many, the economy and environment are two separate issues. But when both are struggling — not getting tangibly better for most people — the collateral damage unlimited economic growth requires starts raising otherwise complacent eyebrows. As the mainstream media works to fit the debate about economic inequality into a bootstrap-capitalist versus freeloader-socialist box, here are some of the realities fueling the skepticism:

- The wealth of the 400 richest Americans now exceeds that of 80 million families—62 percent of Americans.

- A recent survey found that nearly half of working Americans have no savings.

- Corporate America is shoveling staggering sums into a thoroughly hijacked political system, as underfunded schools teach kids they probably shouldn’t bank on polar bears, Social Security or the state of Florida being around when they get older.

- Corporations have the same rights as people and routinely demonstrate their power to supersede the will of local communities that oppose them.

- Cities are experiencing homelessness “emergencies,” while too many of those with jobs are allocating the bulk of their stagnant wages to skyrocketing rents, nervously hoping they don’t need to take their car into the shop or have a medical procedure (the deductible of many ACA health plans being anything but affordable).

- An honest appraisal of unemployment in this country would reveal a significantly higher rate than the official 5 percent (10.4 percent for African Americans), while many of the jobs being added in the growing service industry fall short of providing any actual financial security.

According to a recent Gallup poll, 63 percent of Americans feel this economy unfairly distributes its wealth. Whatever “fairness” is, that’s plenty of people, on all sides of the “aisle” (let’s just call them “folks”), currently under the impression that a sizeable chunk of the collective we is in the process of getting fleeced. In other words: if this is the new economy, perhaps we need a newer one.

May 30, 1983. (Photo: Time Magazine Archives)

Gar Alperovitz — a political economy professor at the University of Mayland, historian and author of numerous books on the topic of corporate capitalism’s increasingly conspicuous pitfalls — is a well-known voice in the national discussion.

He believes that the path to both greater income equality and ecological sustainability (something he calls “an evolutionary reconstruction”) must begin with the democratization of ownership. Today, worker-owned means of production, the fundamental tenet of traditional socialism, is a foreign concept to many Americans. For others, it’s code for a historic pathway to brutal dictatorships. But Alperovitz says that cooperative ownership, as a guiding thematic principle, can be (and in some cases is already being) adapted in a uniquely American fashion.

He tells Rural America In These Times, “To move to a whole different conception we’re going to need new language. The socialist language very often ended in state socialism. So we’re going to need a new one to talk about a community-base building towards a different vision, a pluralist commonwealth — worker, neighborhood, regional and national forms of democratic ownership.”

Others, like Janelle Orsi, the cofounder of the Sustainable Economies Law Center (SELC) in Oakland, Calif., are working where they live to advocate for an economy based on localized sharing and cooperation. By helping others navigate the legalities of non-traditional business or living arrangements, SELC is hoping to foster something they call “community resilience.”

Thank God for Netflix but this is not a lazy generation

Justifiably jaded about what Washington can accomplish these days, the new economy movement — a yet-to-be singularly defined group of people and organizations working to find sustainable alternatives to corporate capitalism — is not placing its eggs in a political basket. But if anybody out there is still wondering why a mean-spirited billionaire shouting anti-establishment rhetoric in a “Make America Great Again” hat and an independent socialist from Vermont are dominating our 2016 election cycle, it’s safe to assume they’ve been out of the labor force for a while — likely drawing their income from fairly reliable stock market dividends (returns on pre-existing wealth).

Wall Street — the often touted symbol of “see, everything’s okay” in the economic recovery debate — has been cruising high above Main Street since the financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent Great Recession. (The right language can take the sting out of almost anything.) Some, however, argue that even these markets are being artifically propped up in the form of unprecedented “easy money” policies implemented after the last collapse. “Quantitative easing” to the tune of $4 trillion — known to these critics as “corporate welfare” — and the Federal Reserve’s reluctance to raise the interest rate from its 7-year stay near zero (ZIRP) have indeed culminated in tremendous market gains. And who knows where we’d be without it? But this wealth does appear quarantined, locked in a cycle of gravity defying sideways and upward “trickling” — largely divorced from the world outside of Wall Street. David Stockman, the former head of President Ronald Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget, calls these methods “the ‘great deformation’ of American capitalism”—methods that essentially turn our financial markets into what he calls “dangerous, unstable casinos.” Is this true? Who benefits from this “easy money” policy? And who ultimately pays for these messianic measures?

Whether these chickens will come home to roost is an open question. But if our society ever chooses to have an honest conversation about the notion that certain institutions are “too big to fail,” these are some very important mother cluckers.

Gar Alperovitz is a historian, political economist, activist and proponent of a new economy. (Photo: garalperovitz.com)

What then must we do?

Gar Alperovitz in his latest book, What Then Must We Do: Straight Talk About the Next American Revolution, argues that the economic and ecological problems we are facing constitute a systemic problem, not a political one. He suggests this is most readily gleaned through a long-term lens — by understanding that the level of economic inequality and ecological decay we are currently experiencing took decades to develop and is not a result of one political failure here or the wrong candidate there. In other words, this phenomenon is the byproduct of how our modern institutions were designed.

He suggests that, though to a less violent extent than state socialism, corporate capitalism has also proven vulnerable to the elite corruption of its best intentions, resulting in both poverty and “ecological decay.”

Careful not to discourage the everyday citizen’s passion for the political process, however, he writes:

I’m not at all interested in pouring cold water on progressive hopes. Quite the contrary. I’m trying to put something else on the table in clear terms — namely, that if we are to get anywhere in the future, we had better think twice about one of the most important precedents many people rely on when they hold that politics can alter the profoundly powerful trends emanating from much deeper systemic processes.

Looking back at historic social victories, from civil rights and the rise of feminism to the more recent legislation on health care and gay rights, he cautions the reader against identifying these long, arduous struggles as comforting proof that we can count on government to eventually do what’s in our best interests. “What all this has been about is getting into the system,” he writes. “Not changing it.”

On September 19, 1977, 5,000 workers at the Youngston Sheet and Tube Company in Youngstown, Ohio lost their jobs. Their attempt to form a cooperative steel mill failed when the Carter adminsistration decided not to back the effort. (Photo: rustwire.com)

One person, one vote: the democratization of capitalism

All things considered, the redistribution of wealth should be an uncomfortable topic. Historically, the collective response to “let them eat cake” has culminated in the copious spilling of elite blood. (One wonders if that bloody chapter in human history could have been avoided by introducing “systemic” into the French peasantry’s vocabulary.) But Alperovitz doesn’t call for billionaire’s heads on sticks. Nor does he espouse the notion that cultural and financial inequities can be sustainably alleviated by something as mundane as higher taxes on the rich. Rather than working to change policies within our existing institutions, Alperovitz concentrates on the possibility of building entirely new ones. In an otherwise fairly pessimistic ode to our collective circumstances, he informs the reader that such possibilities are not without precedent.

His answer to the titular question “What then must we do?” is multi-faceted, but ultimately rooted in seizing existing opportunities (in many cases ones directly created by the myriad failures of corporate capitalism) to democratize wealth. (If this term elicits an innate Soviet era, “Uh-oh!,” you’re not alone — especially if you’re over the age of 65 — but, for better or worse, studies show that gut reactions to the word “socialism” are changing.)

Beginning with the plight of 5,000 steel workers in Youngstown, Ohio, who, on Monday, September 19, 1977 learned their jobs at Youngstown Sheet and Tube were lost and worked relentlessly against the powerful businessmen and United Steelworkers union leaders of their time to create a worker-owned steel mill that would sustain their community, Alperovitz fills whole chapters with examples of worker-owned cooperatives now thriving all over the country (and world). Ultimately, the Youngstown workers’ effort to create an employee-owned mill succumbed to the Carter administration’s political pandering, but not before revolutionizing the national conversation about alternatives to traditional, corporate business models.

“For a start,” Alperovitz writes, “130 million Americans — 40 percent of the population — are [already] members of one or another form of cooperative.” These institutions exist in virtually every sector — from the electrical co-ops prevalent in many rural areas (“socialist” enterprises around since the 1930s that currently generating 25 percent of the nation’s electricity) to agricultural, insurance, health care, food and retail co-ops, not to mention, perhaps most interestingly, credit unions.

He explains that these community banks, to which more than 95 million Americans belong with an estimated $1 trillion in combined assets, “lie at the heart of a new and potentially explosive movement to break down the traditional barriers to funding nontraditional business models.” For example, he writes that in 2011 and 2012, the “Move Your Money” campaign shifted “hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars away Wall Street and big banks.”

One person, one vote, is the grounding principle behind credit unions and, theoretically, all cooperatives. That means in a co-op money should never buy power or profits — instead, these are distributed based on one’s level of participation. But, as Alperovitz emphasizes again and again, worker-owned companies are far from “the only forms of democratized wealth developing under the radar in the United States.” Thousands of “social enterprises,” from traditional community development corporations (CDCs) to a growing number of “land trusts” that provide affordable housing to areas facing, among other threats, gentrification, are simultaneously working to solve the (systemic and often environmental) problems facing their communities. They are at the same time profiting.

Alperovitz calls the reconstruction of traditional business models — that is, the democratization of wealth among those working for their own social, ecological and financial well-being — an “evolutionary process.” And, perhaps like the first fish that found itself with legs, numerous forces are marshaled against any economic paradigm shift. Because traditional corporations are beholden to shareholders, for example, the mere mention of allocating profits for “social purposes” is currently not just counter-intuitive in terms of maximizing profits, it’s justifiable grounds for legal action against the company.

Before criticizing our nation’s veritable legion of lawyers as somehow “anti-social,” remember that, according to this system of ours, the corporations these individuals are defending are people too. (Though not up to their necks in student loans.) Even rethinking this structure quietly — not amid a deeply polarized populace, half of which is ready to tackle any damn pinko in the name of…who knows anymore — is a massive undertaking. Yet Alperovitz suggests that new forms of socially conscious capitalism, a progressive concept to be sure, needn’t be dissected along right and left lines. He points out that in 1987, it was the Gipper himself who said, “I can’t help but believe that in the future we will see in the United States and throughout the Western world, an increasing trend toward the next logical step, employee ownership. It is a path that befits a free people.”

The Sustainable Economies Law Center

While Alperovitz envisions how our economic institutions and the way that we do business might be transformed over time, Janelle Orsi is working, day to day, to create a people-centered economy on the local level.

In 2006, Orsi, a third-year law student at the University of California Berkley, was focusing on social justice issues like police misconduct and keeping kids out of juvenile hall. “Far too early in my career,” Orsi tells Rural America In These Times, “I was starting to get burned out on the adversarial court system.” She began feeling like she could “work forever” and not make a difference. At some point she asked herself: “How would it look if I were a lawyer that was more proactively helping to create communities that were actually going to sustain people — preventing these problems that are otherwise just getting BandAids?”

She met a local organization called People’s Grocery—a group of urban farmers in Oakland teaching young people how to grow fresh food in neighborhoods with otherwise little access. “They were providing young people with jobs,” she says, “creating actual solutions to the same problems I’d been getting up-tight about.”

The experience left Orsi thinking about the “need for land.” She realized that, in many cities there’s plenty of it, but that that land is privately owned — not shared. Still in school, Orsi decided to write a paper focusing on all the legal issues that would arise around people sharing privately owned land to grow food. Suffice it to say, they were numerous.

“That was an ‘Aha’ moment,” says Orsi, “I realized that I could be a lawyer who focuses exclusively on helping people navigate sharing — drawing up agreements, thinking about liability issues, regulations, ironing out the details of their finances and governance.”

After graduating Orsi went to work for cooperatives — grocery and worker co-ops, helping people buying homes or land together. “These were exactly the clients I wanted to serve,” says Orsi, “but time after time I was finding that there was some sort of legal requirement standing in the way of what these people wanted to do.”

Whether it was regulations preventing two people from purchasing real estate together, the way employees were putting in hours at a food co-op, or securities laws that arose when people tried to pool their funds together, she inevitably encountered systemic opposition. “I started to feel like the legal system was designed to keep people way from each other,” says Orsi, “It assumed people were going to exploit each other, which made it very difficult for people to come together to pool their time, energy and resources.”

In 2009, over coffee with friend and fellow lawyer, Jenny Kassan, who had come to similar conclusions about the limitations of the law when it came to sharing, the two began entertaining the idea of a non-profit called the Sustainable Economies Law Center. “It sounded like a big deal law center,” says Orsi, “but we figured it’d be an on-the-side hobby.” That summer, however, they and students interested in the project petitioned the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to change laws regarding small investments in local enterprises. Partly a symbolic gesture used to draw attention to how prohibitive securities laws are when it comes to enabling people to raise capital from their local communities, SELC’s work lay the groundwork for the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, which Obama eventually signed in 2012.

The project got bigger from there. In 2012 they received a $50,000 grant from the 11th Hour Project and since then additional funding. In September, SELC hired its twelfth staff member.

Janelle Orsi is co-founder and Executive Director of the Sustainable Economies Law Center. (Photo: SELC)

Many of the regulations that stand in the way of the new economy movement’s goals — non-traditional, often cooperative arrangements — emerged in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when Congress started realizing how, when you let an economy run wild, workers get exploited and investments become risky. Businesses were getting bigger and bigger and the government saw a need to intervene.

“All of these regulations were created out of good intentions,” says Orsi, “and they remain important to the extent that we still have an economy dominated by large-scale players and those players do have incentive to exploit people — to squeeze as much as possible out of labor and our environment as they can.”

Orsi rarely ever suggests changing those regulations as they apply to large companies, but she does think we “need to create a whole new legal framework that recognizes when you create cooperative businesses, for example, the inherent legal framework is so different that we should probably have different regulations for them.”

SELC’s Policy Director, Christina Oatfield, leads the organization’s Food Program while supporting the Grassroots Finance part of their mission. In addition to a nationwide campaign to promote seed sharing among growers, they’ve recently drafted the Local Economy Securities Act (LESA) — a bill in California that would exempt small local investments in community businesses from state permit restrictions. In doing so, it would also allow a small farm enterprise to raise up to $2 million for the “purchase, long-term leasing, purchase of an easement, construction or improvement of real property to be used for agricultural purposes.” “This bill is currently pending legislation,” says Oatfield, “and probably our biggest project related to Grassroots Finance at the moment.”

“The important things we consume — housing, energy, water, food — should be consumer owned,” says Orsi. “Because of the work we do, and services and goods we provide for society — to the extent that we’re spending a good portion of our lives working for them — we should be in control of our work environment. It’s hard for me to see many business out there that shouldn’t be worker owned.”

Ultimately, however, SELC is about more than the advancement of cooperatives — cooperation itself, is an undercurrent. “Behind everything we do,” says Orsi, “is the idea that most of our economy should come into legal structures that are either cooperative or not for profit, because that removes the incentive for exploitation and distraction. We keep coming back to the idea that worker co-ops are absolutely essential if we want to create sustainable livelihoods.”

Questions

The need for an economic overhaul that works for working people — one that doesn’t leave a legacy of perpetual debt, environmental destruction and unreciprocated corporate servitude —is obvious to many. But where are we headed and what can we do about it?

Are the TaskRabbits and Uber drivers of today the ushers of a new, fend-for-yourself, do-whatever-it-takes economic model?

Are these freelance warriors — seizers of the so-called “gig economy” — 21st century corporate refugees, resourceful people drawn by economic necessity to the flames of app driven start-ups that offer a perpetually casual Friday but little in the way of long-term security? Indeed, are employer-provided health care, two weeks paid vacation, a matching 401k, parental leave, etc., anachronisms for those without strong bootstraps and a relatively reliable Toyota Corolla?

Considering the extent to which our political processes have been monetized by corporate influence, can the relationship between people, wealth and the environment be improved without government intervention? Is it possible to create a more equitable society without all-out social warfare being the catalyst?

Maybe, maybe not, but a considerably more optimistic outlook presents itself if one scales these questions down — replacing “society” with “town,” “city” or “community.” Like the problems themselves, sustainable solutions on the same scale will take time (perhaps generations) to fully manifest. But employing a community’s existing resources — the most valuable of which are the people who are directly invested in its sucess — to their fullest potential, whether that is establishing an employee-owned business, arranging to grow food on an empty lot, or choosing to take capital out of the increasingly “unstable casinos” and put it to work in the local economy, might be worth a shot.